Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

Nothing is more important in the memory of Salvador than its historic buildings, including its forts, fortresses and defences.

Among them are the fortifications, which have become obligatory in the images of postcards, tourist advertising pieces and other documents about the city.

According to the English military and historian Charles Boxer, the presence of a single fortress is an item that justifies a visit to any city.

Salvador can still display many of them, in a reasonable state of preservation, capable of evoking the past and the memories of upheavals, revolts and invasions of our soil.

Although it may seem paradoxical that fortifications are set against the backdrop of violent combat, they have had a great poetic appeal since the Middle Ages and even before.

They captivate and fascinate the observer of our times, regardless of the intense historical background that they accumulate and which, in itself, would already hold enormous appeal.

The prominence of the fortifications in the city’s landscape certainly represents the tactical and strategic necessity of positioning them in an elevated location, with privileged visibility to the surrounding areas.

But the military engineer who designed and built them cannot be denied the aesthetic sensibility he assimilated from the culture of his time and from the texts of the most prominent theoreticians of Renaissance and Baroque architecture.

The treatises of these engineers are full of quotations from the masters of architecture of the past, whose teachings undoubtedly contributed to the formation of their creative sensibility.

The bastioned fortifications are not far behind. Even though they are influenced by the rationality of the new era, which is essential to counter the great destructive power of firearms, they show the coherence of the resolution of the function, which almost always leads to the quality of the form.

In this area, where no concessions could be made to the superfluous, the result was usually a good architecture, with very pure forms, harmoniously arranged volumes and perfect integration with the morphology of the terrain.

Formal simplicity is inherent to the function, and there is no appeal to decorative resources, which could make the fortified work more fragile from a tactical point of view.

When they existed, decorative concessions were more than limited: a bocel or cordon separating the parapet from the skirt (the sloping part of the wall below the parapet), but which had a certain practical function; a portcullis, with ornamentation inspired by the ancient Greco-Roman orders, especially the Tuscan (a variant of the Doric); some moulding on the sentry boxes and basta.

Two moments in the poetics of “modern” fortifications should be characterised:

- In the first, construction was entrusted to Renaissance architects and artists, who endeavoured to do their best to sell their models to potential contractors, especially in the 16th century.

- In the second, construction was entrusted to Renaissance architects and artists, who endeavoured to do their best to sell their models to potential contractors, especially in the 16th century.

- In the second period, the task of fortification passed to military engineers and the trend towards sobriety intensified. It is not that engineers departed from the canons of beauty, but the pressing need to counterbalance the destructive power of weapons of war increasingly pointed to pragmatic solutions.

Videos about Fortresses and Defences of Salvador

História do Forte de Santo Antônio da Barra25:49

História do Forte de Nossa Senhora de Monte Serrat 26:56

História do Forte de Santa Maria em Salvador - BA28:03

História do Forte de São Diogo em Salvador BA27:41

História do Forte de São Marcelo ou Forte do Mar

Fortresses and Defences of Salvador BA

A History of Three Centuries

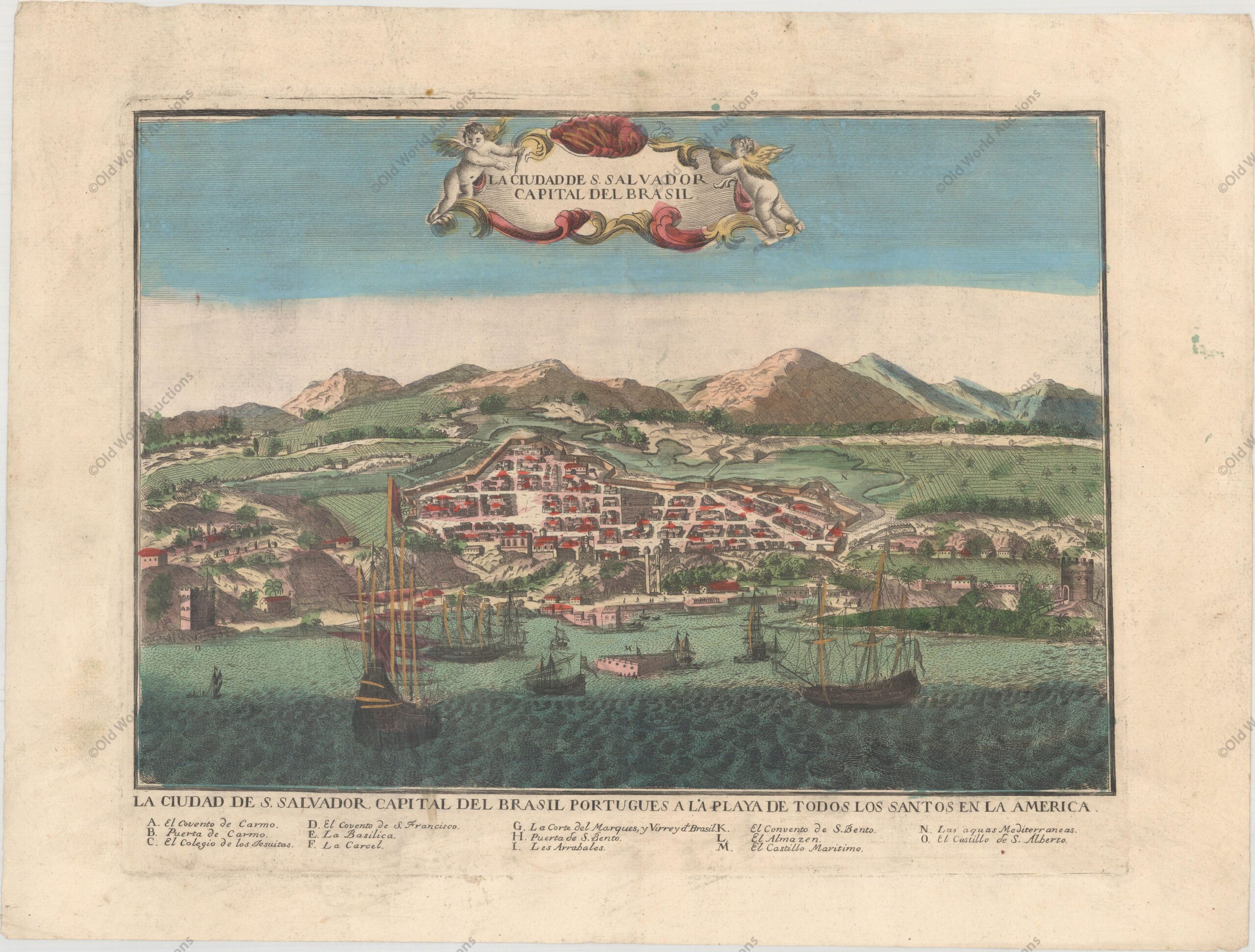

Salvador was born as a strong city, or at least that was what King João III of Portugal intended, and while it was the capital or head of Brazil, there was constant concern to defend it.

For this reason, the first Governor-General of the Colony, Tomé de Sousa, who was commissioned by the king to install the capital, brought with him, in 1549, the master Luís Dias, an expert in fortifications.

Dias applied the “traces” (drawings, projects) from the Kingdom on the ground, raising high rammed earth walls to defend the nascent capital of Portuguese America.

.It is necessary to recognise that, contrary to what some ufanistic historians have claimed, Salvador remained very vulnerable to external attacks by modern armies.

to external attacks from modern, well-organised armies of the time, equipped with artillery, which had already become reasonably efficient by the 17th century.

The vertiginous and disordered growth of the city, especially from the 17th century onwards, made it difficult to build a secure fortified perimeter, in accordance with the good postulates of the art of defence of those times.

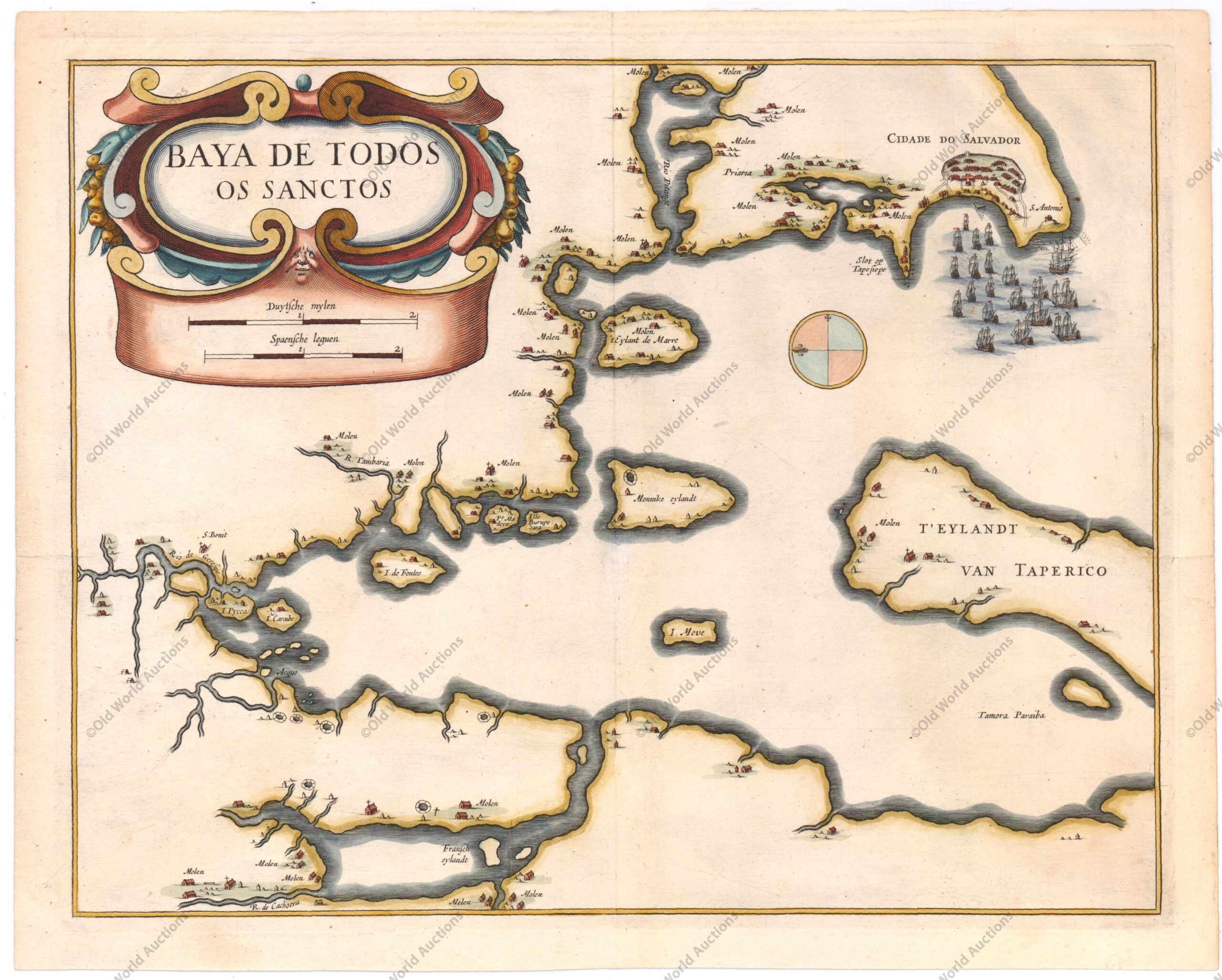

In the case of the Baia de Todos os Santos, the problems multiplied because, as one of the largest bays on the planet, the openness of its bar meant that it was impossible to restrict the access of enemy ships, which could pass offshore, far from the reach of the cannons, without being harassed by artillery.

In addition to these difficulties, there were financial limitations: Portugal was not a rich country and the Royal Treasury opened its coffers very sparingly for investments in America, in view of the problems it had with the possessions and colonies of Africa and Asia and the indebtedness to European countries.

The development of our fortifications was thus mainly dependent on taxes on wine, sugar, whale oil or other trade products.

The inflow of these resources, however, was not compatible with the needs of a large-scale fortification, as the defence of the capital required.

Concern about Salvador’s vulnerability is not simply an impression that can be inferred from reading old documents.

It is made clear above all in the writings of specialists in military affairs, particularly the engineers who worked or lived in the city.

Diogo de Campos Moreno, for example, sergeant-major and captain of the coast of Brazil at the time of Governor-General Diogo Botelho, highlighted the fragility of the city’s defences in a report of 1609.

However, there were those who considered our defences to be “sufficient”, as in the case of D. Francisco de Souza, Governor-General of the great Portuguese colony of overseas between 1591 and 1602. One can only make two interpretations of this disgraceful opinion:

D. Francisco did not understand the subject, which was quite likely, or he was trying to justify the fact that he did not take better care of the situation when he was in a position to do so.

The Livro que dá razão do Estado do Brasil – 1612, attributed to Diogo de Campos Moreno, is quite incisive when it comments on the state of the defences of the Head of Brazil: “this prison should be sustained while the fortification of the citadel is so far behind schedule and the city is an open village, exposed to all dangers as long as that part is not fortified […]”.

.

There was no shortage of other warnings to the courts of Portugal and Spain about the precarious state of our defences.

In the years leading up to the Dutch invasion of 1624, in the face of rumours of preparations by the Batavians, there was an intense exchange of correspondence on the subject.

But at that time, the need to build the Forte da Laje, the controversial defence of the port of Salvador, which many historians have confused with the Forte de São Marcelo, was still being discussed.

.

But what Diogo Botelho wanted was much more than that: he was clamouring for a citadel, given the difficulty of protecting the entire perimeter of the capital.

Because the fortification of Salvador had not been completed, the Dutch entered it with the greatest of ease in 1624..

When they took possession of the square, they tried to fortify it because, as good specialists and belonging to one of the most respected European schools of fortification, they considered the city unprotected to guarantee their defence.

The first measure the invaders adopted was to clear the fields around the city.

They cleared not only the bush but also some of the buildings that obstructed the visibility of the shooters.

They set up defensive earthen positions at the hermitage of Saint Peter (neighbouring the present-day Fort of Saint Peter) and at the present-day hill of Barbalho; they also organised defences at Saint Anthony Beyond the Carmel; they dammed the River Tripas, creating the Small Dike, which later came to be called the Dike of the Dutch, along the present-day Baixa dos Sapateiros, and other protections.

These fortification works are recognised in official Portuguese documents and by chroniclers of the invasion and retaking of the city of Bahia from the Dutch.

the Dutch of the city of Bahia, including Johann Aldenburgk, a doctor in the Dutch squadron, and the Spaniards Tamayo de Vargas and Valencia y Guzmán.

In the period following the invasion and retaking of Salvador, it was clear that it was important to fortify the city and the Morro de São Paulo, the key to the defence of the Three Villages, the former name in royal documents for Cairu, Boipeba and Camamu, considered, verbatim,

as the granaries that supplied Salvador.

The full demonstration of the fragility of our defence system, given by the seizure of the capital by the Batavos, meant that, even involved with the wars of the Restoration, the Portuguese government decided to improve it, investing some resources from the Royal Treasury, but,

mainly by creating more taxes on goods.

In the city, some defences were restored and/or improved, especially during the administration of Dom Diogo Luís de Oliveira (1627-1635), as the Dutch enemy continued to threaten to invade.

Resentful of the attempted conquest by Nassau in 1638, and even after Portugal regained autonomy from Spain (1640), the Lusitanians undertook some defensive works, especially during the short-lived but enlightened administration of Viceroy Jorge de Mascarenhas, the first Marquis of Montalvão (1640-1641).

These works, however, concentrated on reinforcing some existing positions and restoring old defences, especially those left by the Dutch in 1625.

Under Governor Antônio Teles da Silva (1642-1647), Montalvão’s works continued and construction began on the extended perimeter of new trenches.

Needless to say, the Portuguese Crown invested little in this endeavour, which was carried out with funds from taxes and voluntary contributions from the inhabitants of the city and the Recôncavo.

An idea of this new fortified perimeter can be seen in the drawing of the plan of Salvador, drawn up much later, in 1714, by the French military engineer Amédée Frézier.

In the mid-17th century, construction began on the Fort of Nossa Senhora do Pópulo e São Marcelo, a design influenced by that of the Bugio Fort on the Tagus River bar. The work, intended to prevent landings in the city’s harbour, dragged on for many years, until the 18th century.

However, an anonymous report, probably dating from 1671 or 1672, did not contain very flattering remarks about most of the fortresses mentioned.

At the end of the 17th century, Captain Engineer João Coutinho arrived in Salvador from Pernambuco at the behest of the Court. Only then was a large-scale plan attempted to defend the city, which the captain found unprotected.

Coutinho’s project was never executed, except for some parts. A statement in this regard is contained in the speech of Bernardo Vieira Ravasco (brother of Father Antônio Vieira), who was Secretary of State and War for many years: “The Engineer [João Coutinho] died, then Governor Mathias da Cunha, everything remained the same until today, and only the ruins and the trees grew in them […]”.

One of the main reasons for the difficulties in defending the Head of Brazil was the disorganised growth of the city.

It is true that there were ordinances and regulations that were supposed to discipline the occupation of the land, but people lived thousands of kilometres away from the Kingdom and a strong attack

kilometres away from the Kingdom and a strong atavism encouraged non-compliance with rules.

Abusive constructions took over the urban space, with the “blind eye” of some administrators and even with the authorisation of the City Council.

The council was benevolent towards its friends and protégés, authorising what it could not authorise under the rules, i.e. building “on the salt flats”, as the sea land was called, which belonged exclusively to the King, who was responsible for granting such permission.

Added to this was the invasion and use of trenches and redoubts as backyards, the removal of gravel from fortifications for the construction of private houses, the use of fortress moats for cattle grazing, the opening of accesses through escarpments and counter-escarpments and similar works.

The Lower Town suffered most from disorganised growth.

The foot of the mountain was cut off to build buildings, mainly in the interests of traders who wanted to take advantage of the small strip of land between the escarpment and the sea.

As a result, problems with the stability of the slope and the encroachment of the sea with buildings, blocking the firing range of the few existing forts, estancias and platforms, made the defence of the port impossible.

The report by Captain Engineer João Coutinho in 1685 and the documents by military engineers who succeeded him in the early 18th century clearly delineated this situation, which seems to have continued throughout the century.

As the century drew to a close, the threat of invasion continued and the Portuguese Crown once again decided to build a decent fortified system for the Portuguese capital of the Americas.

Early on, in 1709, Field Master Lieutenant Miguel Pereira da Costa was sent to Bahia as a permanent engineer.

Through correspondence, he expressed his despair at finding a city completely unprepared and without defences to face any possible enemy.

In a letter of 18 June 1710, he wrote to a certain Father Mestre, possibly a Jesuit and his former teacher: “[…] everything is here in the greatest helplessness, the square open and exposed to any invasion […]”.

In a preliminary report, he commented: “[…] these are the works that are in this square for its defence and all in a miserable state […]”.

The Portuguese Crown’s recognition of the fragility of the defences of important Brazilian cities such as Salvador, Recife and Rio de Janeiro led the Portuguese monarch to give João Massé the rank of brigadier to come to Brazil.

His mission was to improve the defences of these and neighbouring towns.

In Salvador, Massé had the collaboration of local engineers who already knew the reality of the terrain, such as Master-fielder Miguel Pereira da Costa and Captain Gaspar de Abreu, a professor at the Military Architecture School in Bahia.

As always, little of the majestic fortification project proposed for Salvador, whose original drawings have been lost but copies of which remain, was actually carried out, with the defence of the prison being left for later.

The same happened in other cities.

The move of the capital to Rio de Janeiro in 1763 put an end to the possibility of Salvador being adequately fortified. The Pombaline period was passing and it was the Marquis himself who reported on the state of our defences in a letter to the Viceroy of Brazil, dated 3 August 1776, On the Verisimilar Project of Invasion, Bombardment and Contribution, or Looting, of Bahia de Todos os Santos.

In this document, His Excellency said that the Marquis of Grimaldi had advised the King of Spain not to attack the southern part of Brazil, which was better garrisoned and more distant: “that he should order attacks on other more convenient and safe places; or on the ports where we are most unprepared, which are Bahia and Pernambuco”.

In short, the Portuguese government was not unaware of the weakness of our defensive situation.

The First Walls

Documents from the time provide an interesting detail about Salvador’s defences in the early days. They were erected much more out of fear of the natives than of foreign invaders.

This way of looking at things would only change with the passage of time.

Taking this information into account, it can be said that, in the early days of its foundation, the city enjoyed reasonable defence conditions.

Even though they were skilful archers, knew the terrain and were men of unusual courage, the natives could not oppose the coloniser with anything other than their rudimentary weapons.

Therefore, the precarious rammed earth wall, which had the flavour of a medieval defence, was adequate to deal with this threat.

Erected under the guidance of the master Luís Dias, the wall followed general plans from the Kingdom, attributed to the architect and military engineer Miguel de Arruda.

It so happens that the city grew rapidly, as the chroniclers explain, including the Portuguese coloniser Gabriel Soares & nbsp;de Sousa, author of the Descriptive Treaty of Brazil in 1587, or Notícia do Brasil.

Thus, as the greed of other European peoples made the Brazilian coast the scene of incursions by corsairs, adventurers, smugglers and, later, companies supported by nations, Salvador, the Head of Brazil, became a target of growing interest.

Documents from the 16th century, such as the correspondence of Luís Dias himself and the Provisions for the payment of contractors, speak of the preliminary rammed earth wall, which, according to the Bahian historian and folklorist Edison Carneiro (1912-1972), was 16 to 18 palms (3.52 m to 3.96 m) high.

When it was rebuilt after the collapse of the invernadas in 1551, it became 11 palms (2.42 metres).

As to its extent and exactly where it passed, there is only conjecture, since no evidence has been found other than a stretch of wall at the gates of Carmo.

However, even with the reduction in height and the application of protective plaster, these defences were very short-lived, as Gabriel Soares de Sousa attests. The defences, which were rebuilt using the same technique by Governor-General Francisco de Souza, who managed the colony between 1591 and 1602, were also short-lived.

The Redoubts Built by Luís Dias

The rammed earth walls that surrounded the original Cabeça do Brasil were not sufficient for the city’s defence, particularly because of the altitude at which it was located (around 70 metres above sea level).

This situation, in a way, made it difficult for the enemy to take the city from the harbour, forcing them to climb steep slopes, but it did not help to prevent the landings, because the artillery of the time, working at that height, had a sharp dark field and could not shoot downwards.

and could not fire downwards.

In response to the problem, Luís Dias endeavoured to create some platforms, stations or even redoubts in the Ribeira area (formerly the lower part of the city, by the sea).

These elements, mentioned in a missive by the master himself, were intended to protect the harbour, making it difficult to land.

The location of these first propognacles of Salvador is still a subject of much controversy, although mined by illustrious figures in Bahian historiography.

of Bahian historiography.

In general, it is assumed that six defences supported the rammed earth wall that surrounded the new city at the time of its foundation.

This number is based in part on references by Gabriel Soares de Sousa, which we believe to be quite reliable.

However, he does not give the names of all the positions equipped with artillery.

The two sea fortifications that Luís Dias mentions verbatim in one of his letters were built on the beach to defend the port.

The author reports that the first of them was made of earth and “mangrove sticks that grow in the water and are like iron”, which he thought could last about twenty years, leaving it to the royal discretion to decide whether to build them in stone and lime.

Historians disagree on the exact location of these missing defences.

However, according to almost all scholars who have read Dias’ document, one of them was located in the Ribeira do Góes, on top of a rock.

It is known that the other defence was called Santa Cruz and that it must have been smaller due to its armament.

- Engineer and geographer Teodoro Sampaio (1855-1937), a scholar of the city of Salvador, points out four bastions facing the land.

- The bastion of São Tomé, which protected the gate of Santa Luzia and the road to Vila Velha do Pereira, located on the site of the current Praça Castro Alves.

- A bastion facing the land.

- A bastion “in an acute shape with flanks and faces advanced to the northeast”, next to a certain noble house, with an entrance door surmounted by coats of arms (possibly the Solar dos Sete Candeeiros, in the vicinity of the current building of the Institute of Architects, on Ladeira da Praça).

- A bastion at the end of the alley of Vassouras, later known as the alley of Mocotó.

- Finally, a bastion at the head of the depression where the church of Barroquinha is located. This position must correspond to the site of the former Guarani cinema-theatre, later named the Glauber Rocha, in what is now Castro Alves Square.

As can be imagined, this location of the bastions establishes another huge dispute. It goes back to Gabriel Soares de Sousa, who said in 1585 about the primitive walls: “now there is no memory of where they were”; it is therefore very difficult to be sure of the location of anything.

In addition, the plans of João Teixeira Albernaz I, which are part of the Book that gives the reason for the State of Brazil, the basic foundation of the historians’ arguments, are not registers, but plans for the citadel that Diogo Botelho requested.

These plans may have been drawn up differently, partially executed or not realised at all.

Thus, we cannot use these plans to argue that the first gates of Santa Catarina were located on the north side of Praça Tomé de Sousa (Municipal Square), at the beginning of the current Rua da Misericórdia.

However, it is worth admitting the situation proposed for this primitive access as a possibility, because the arguments presented, even if they are not convincing, allow several interpretations.

The Early Towers

Nothing remains of the primitive defence towers of the former capital – mostly buildings erected of rammed earth that time has taken care to consign to the realm of oblivion.

This is not only because rammed earth can be an ephemeral construction technique when not executed with care, but also because these fortifications have become obsolete in the evolution of the art of defences.

Fortunately, written history and iconographic elements have survived which allow us to recover, with a certain degree of certainty, something of the memory of this primitive moment in our fortified systems.

Everything indicates that the tower, with its medieval foundations, played an important role in the design of fortifications for almost the entire 16th century in Portuguese America, both under the regime of hereditary captaincies and during the first moment when the decision was made to create the City of Salvador.

Initially, it should be emphasised that this concept of the construction of our towers was put aside by some historians, claiming that the meaning of the term tower was linked to the symbolic concept of fortification in general. The cause of this misconception is that they did not delve deeper into the research, combining the historical information contained in the texts and the state of the art of defence in Portugal, with the support of field observations made possible by archaeological prospections.

The first argument that can be raised about the existence of towers is that, in the 16th century, Portugal still retained medieval customs and traditions.

At that time, the tower was the central element of any fortified system, and was even an isolated and solitary building when the lord of the land was not wealthy enough to surround it with a perimeter of outer walls.

This system was enough to protect the first colonisers against the rudimentary weapons of the original inhabitants of our land.

The word “tower” is mentioned in ancient documents and royal ordinances and there is no reason to suppose that the term was used in a figurative sense, especially since iconography and traces of the Tower of St James of Agua de Meninos have been found.

It is true that the artists who produced the engravings took poetic licence in placing towers everywhere.

However, when the drawing had a documentary rather than illustrative purpose, the representation of the fortresses was closer to the real thing.

It is therefore not unlikely that the first square-based defence towers were the fortifications used by the grantees in their captaincies.

The historians Francisco Varnhagen and Capistrano de Abreu come to our rescue with a transcription of a document from the National Library in Rio de Janeiro, which explains the appearance of Vila Velha by Francisco Pereira Coutinho, the grantee of the captaincy of Bahia: “He placed the village on the best site he could find, in which he has built houses for a hundred inhabitants, and a tower on the first floor”.

Pereira Coutinho’s tower in Vila Velha (where the church of Santo Antônio is located) must have been similar in all respects to that of the grantee Duarte Coelho in Pernambuco, which was, according to Varnhagen, “a kind of square castle, like the keep towers of the manors of the Middle Ages”.

It is not difficult to see in the plan drawing of the primitive Fort of Saint Albert, in the lower left-hand corner of the iconography bequeathed to us by Albernaz, the design of these square towers, whose entrance was flanked by two smaller corner towers.

It should be noted, for example, that Pereira Coutinho’s tower in Vila Velha was already in need of repairs when the city was founded, as indicated by a Provision of the time for the reconstruction of 31 fathoms (68.2 metres) of its rammed earth by the taipeiro Balthazar Fernandes.

A variant of the old rectangular towers was the use of a circular design, but with an entrance also flanked by smaller towers. An example of this version can be seen in the top left-hand corner of Albernaz’s drawing (p. 44). As the records of military engineer José Antônio Caldas and chronicler Luís dos Santos Vilhena attest, this tower survived until the end of the 18th century, incorporated into the additional embankment designed by field master Miguel Pereira da Costa in the first quarter of the same century.

It was the Tower of São Tiago de Água de Meninos, later the Fort of Santo Alberto (when the original one disappeared), commonly known as Fortim da Lagartixa.

Not even fifty years after the foundation of the capital, the Portuguese colonisers already felt that these defensive systems had become ineffective in stopping an organised troop and withstanding the punishment of large calibre artillery.

The Conditions of Defence of the City

A few years after Gabriel Soares had described the pitiful state of Salvador’s defences, D. Francisco de Sousa arrived in the city to head the great overseas colony. Friar Vicente do Salvador, a 17th-century historian and chronicler from Bahia, says that D. Francisco “was the most favoured governor there was in Brazil”.

From 1591 to 1602, he exercised his authority with gentleness, became very friendly with the population and applied himself to improving local defences, according to the chronicler.

The new governor-general was accompanied by technicians, including the military engineer Baccio de Filicaia, who possibly designed the fortifications built during the period.

Friar Vicente do Salvador reports that Dom Francisco “built three or four stone and lime fortresses”. The number four is probably accurate, since the constructions are understood to be the Fortress of Santo Antônio da Barra, the Fortress of Itapagipe (Monserrate), the Fort of Água de Meninos (Lagartixa) and the Redoubt of Santo Alberto (Church of the Holy Body), as well as new rammed earth walls for the city.

To elucidate this moment in history, more important than Diogo Moreno’s Livro que dá razão do Estado do Brasil (Diogo Moreno’s Book that gives the reason for the State of Brazil) is the report made by the same author in 1609, which describes the location of the fortified positions. As the purpose of the document was not to list defence points but artillery, the simplest platforms, which were armed only when necessary, were not mentioned because there were few pieces available and/or so as not to leave them in the open.

Thus, the 1609 report mentions the following fortified positions, most of them facing the sea, with the exception of the two gates in the north and south directions:

- St Anthony, at the entrance to the bar, in the letter A, which was made to defend it […].

- At the entrance to the city, at the gate of St Lucy, there is an instance over the same gate […].

- […] Over the Church of the Conception was another instance with two bronze pieces.

- In the middle of the mountain, under the House of Mercy, there is also a platform that defends the slope at the point near the City […].

- […] at the foot of it (Estância da Santa Casa) so that he can throw [throw] the fire of (water?) is Santo Alberto estância of stone and lime that Dom Francisco de Souza made […].

- […] at the foot of the College of Jesus is another very high platform that looks out over the whole harbour and in the (illegible) to the water of the boys […].

- […] at the last door that goes to Carmo is another cubelo that defends that entrance […].

- […] on the city beach, at the end of the trenches on the side of the old emptying place, there is a resort […].

- […] further along [also on the beach], in the houses of Baltazar Ferraz are two pieces […].

- […] further along the beach are two more bronze falcons […].

- To the north of this city, one league away, there is another point called Itapagipe, which is marked with the letter G on the plan, from where there is another stone and lime fort of the same design as S. Antônio (da Barra).

- […] further along the beach there are two more bronze falcons […].

- […] in another estancia that lies between this Itapagipe and the city they call Água dos Meninos […].

According to Teodoro Sampaio, in addition to building the four fortifications already mentioned, D. Francisco de Souza started “the Fort of St Bartholomew at Ponta de Itapagipe, intended to seal off the entrance to the Pirajá estuary”.

This site was in the neighbourhood of the present-day Parque de São Bartolomeu, whose toponymy originated in the name of the fortress.

Master Teodoro was very judicious and must have taken this information from some document, but he does not say whether he had access to any primary source that would clarify the matter.

The typology of the Fort of Saint Bartholomew (a star-shaped polygon) also seems strange in relation to other drawings of the time, which does not justify an absolute denial of Teodoro Sampaio’s statement, since the known drawing may have been the result of later alterations.

This happened with other forts, such as Barbalho, Santo Antônio Além-do-Carmo and the current Santo Alberto, which changed their physiognomy, or Santo Antônio da Barra, which metamorphosed completely a few times.

It is the same Teodoro Sampaio who claims that it was Diogo Botelho, successor to Dom Francisco de Sousa, who was responsible for the Fort of São Marcelo.

Marcelo.

It is a point on which one must disagree, but one that is widely followed by several historians.

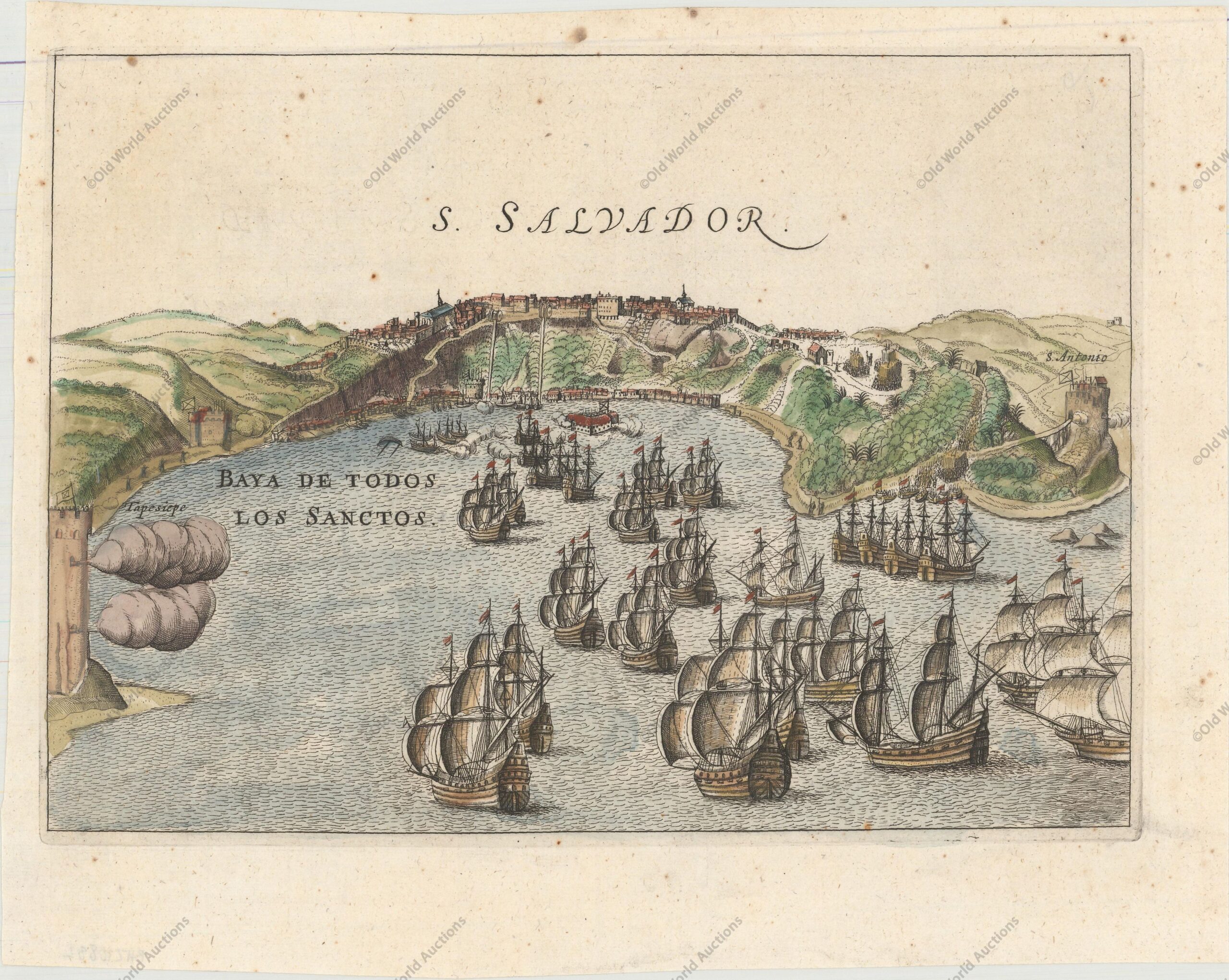

The engraving by the Dutch cartographer Hessel Gerritsz, reproduced below, is very illuminating because of its unusual fidelity to the elements of the defence of the City of Salvador, just after the invasion of 1624.

As has already been pointed out, in most cases the artists’ poetic licence added some fantasy to reality.

In Gerritsz’s drawing, however, the artillery positions are indicated by the smoke of the cannons and often by the inscription of the word “fort” or “battery” in Dutch, frequently corresponding to Diogo Moreno’s description.

The drawing of Fort da Laje, known at the time as Forte Novo (Nieuwe Fort), shows the actual configuration of the defence. It shows the

The fort is positioned above the hermitage of the Conception, the St Diogo fort below the Misericórdia, the stone and mortar fort of St Albert and the very high platform at the foot of the College of Jesus, which should have been the pottery of the Company’s priests (potte backery), from where we could see as far as the Água dos Meninos.

As for the office on the “old emptying band”, it could be the one indicated at the Guindaste dos Padres (Papenhooft), as the lift that carried goods from the Lower Town, the harbour area, to the College of the Society of Jesus was called.

Of the positions represented, only three are not found in Diogo Moreno’s references: the Conceição battery, which is known to scholars; the Palácio battery, also well known and commented on for its uselessness; and a platform in Carmo, which may be the one from the time of D. Fradique de Tolledo, commander of the expedition organised by Portugal and Spain to liberate Salvador from the Dutch in 1625.

This is a really interesting piece of iconography for anyone studying the fortifications of Salvador.