Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

The first attempted Dutch invasion of Salvador took place in December 1599, when Admiral van Leynssen sent seven ships to Brazil, commanded by Captains Hartman and Broer.

At the beginning of the 17th century, Salvador was one of the most important cities in America, the capital of Brazil, a Portuguese state controlled by the Spanish during the Iberian Union (1580-1640).

The attacks in the Bay of All Saints lasted almost two months.

The Dutch sank several Portuguese vessels and plundered mills in the Recôncavo. But they failed to conquer the city.

In the following years, Dutch pirates continued to attack Spanish and Portuguese ships on the high seas, both in the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean.

In 1604, they tried again to conquer Salvador, this time with a squadron of six ships commanded by Paulus van Caerden.

The Dutch invasion of Salvador in 1624

The attack was similar to the first and the result, the same failure.

In the following years, dozens of ships with cargo from Brazil were attacked by the Dutch.

In 1621, the Dutch founded the West India Company (West-Indische Compagnie), a company sponsored by the Dutch government, with the participation of private investors and which sought primarily the commercial exploitation of America.

The city dawns under the domination and effects of the bombardment of a Dutch squadron composed of 26 ships, under the command of Jacob Willekens.

The Dutch invasion of Salvador took place on 9 May 1624.

The day before, even under crossfire from the Fort of Santo Antônio, the Dutch managed to target the cannons of Ponta do Padrão and disembarked at the Port of Barra.

Groups of vanguards follow the Ladeira da Barra and cliffs until they reach the Porta de São Bento.

The Dutch spend the early hours of the morning at the Monastery “savouring the wines and confectionery” they find there.

There, they wait for daybreak and take over the city centre.

According to Ricardo Behrens, in the book ‘Salvador and the Dutch invasion of 1624-1625’, “Portuguese and Dutch accounts tell that the confrontation began the day before when the city’s inhabitants fired on a barge with a peace flag sent by the fleet, even before they heard the embassy.

In response, the invaders unloaded their cannons on the city’s coast, on the forts and on the ships in the harbour”.

The sight of the armada alone caused most of the inhabitants to panic and run.

Even though they knew the attacks were likely, the city had no special strategy. D’El Rey had not established any resources for armaments.

The Dutch – whose fleet had left Texel harbour in December and whose voyage had lasted almost six months – were intent on invading the capital of the Kingdom of Brazil and had plenty of ammunition.

The devastating cannon fire during the Dutch invasion of Salvador and then the vandalism of the invaders, caused numerous damages to the city, including the building of the City Hall where the Historical Archive was installed, whose documents were completely destroyed by fire.

According to the historian Affonso Rui, in his book ‘História política e administrativa da cidade de Salvador’ (Political and administrative history of the city of Salvador) “the officers in charge of the documentation, like a good part of the population, fled to Abrantes”, he reports.

The 3,400 men, including adventurers and mercenaries who made up the invading Dutch squadron, did not encounter any major resistance to surrendering the governor-general of the colony, D. Diogo Mendonça Furtado, and imprisoning him in the so-called House of Governors (in what would become the Rio Branco Palace, in the current Praça Tomé de Souza), in the heart of the city, one of the most important cities in America, then capital of Brazil.

The Portuguese ruler had already expressed concern about Brazil’s military unpreparedness and had even clashed with the Church, which saw no need for military concerns.

So the Dutch had little trouble taking the city and Diogo Mendonça Furtado signed his surrender a day later.

He is taken prisoner to Amsterdam with 12 other people, including auxiliaries and Jesuits, from where they are only released in 1626.

According to Behrens in his Master’s dissertation already converted into a book, “there is a series of conferences published in the Journal of the Geographical and Historical Institute of Bahia, No. 66, 1940.

This was a publication commemorating the defeat of Maurício de Nassau when he tried to invade Bahia in 1638.

In addition to the lectures, the suggestions made by the members of the Institute to commemorate the date were published, among which the idea of making a series of commemorative plaques stands out, like the one that still exists at the entrance to the Monastery of São Bento”.

The Dutch remained in Bahia for almost a year.

It was up to Bishop Marcos Teixeira, later known as the Warrior Bishop, to promote resistance.

Through the tactic of ambushes, he prevents the invaders from leaving the city.

On 27 March 1625, the Portuguese-Spanish reinforcement squadron, commanded by the Spaniard Fradique de Toledo Osório, arrived in Bahia.

The battle lasted more than 40 days and on 1 May the first surrender was obtained.

Colony was controlled by the Spanish during the Iberian Union

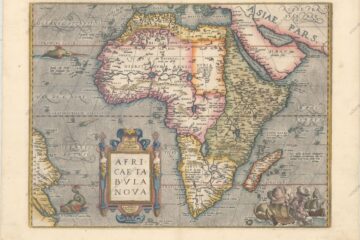

The colony was then controlled by the Spanish during the so-called Iberian Union (1580-1640), which brought the two crowns together after the disappearance of Dom Sebastião de Avis, in the Battle of Alcácer Quibir, in Morocco, in the war against the Moors, in 1578, when he aspired to victory over Muslims for the glory of Christianity.

It’s worth noting that the “death” of Dom Sebastião provoked a succession crisis in Portugal, as the king had left no heirs. His disappearance gave rise to “Sebastianism”, a kind of messianic belief that stipulated his return to the kingdom and that would last for three centuries as a symbol of Portuguese nationalism.

The solution found for the throne is his great-uncle, Cardinal D. Henrique (Henry I of Portugal), who, already quite old, dies in 1580, marking the end of the Avis dynasty.

As a result, the Portuguese throne became disputed by other European dynasties, which claimed kinship with Dom Sebastião.

The then king of Spain, Felipe II, one of the most powerful monarchs of the time, was the grandson of Dom Manuel, O Venturoso, who, in turn, was Dom Sebastião’s uncle.

This parental connection was claimed by Felipe II and used as legitimisation for the invasion of Portugal by the Spanish in 1580, establishing the dual monarchy: two crowns under one monarch.

Portugal only regained its independence 60 years later when the reign of King João IV, founder of the Braganza dynasty, began.

It was during the period of the Iberian Union that the French invasions also took place.

The Netherlands and France, which had previously maintained a friendly relationship with Portugal, clashed directly with Spain.

Iberian supremacy was questioned by those European nations that also wanted to profit from the colonisation process.

This involved both economic reasons, such as control of the sugar trade and metal extraction, and religious ones, since Spain was Catholic while the Netherlands and part of the French had adhered to Protestantism.

The period known as “Dutch Brazil”, in which a sophisticated Dutch administration prevailed in part of the northeastern Brazilian coast, occurs exactly in this context.

There are no records of Dutch legacies in Bahia, unlike those in Pernambuco, such as the French in Rio de Janeiro and Maranhão.

First attempted invasion takes place in 1599

Other attempts by the Dutch to invade Bahia had already been recorded, but were unsuccessful.

Unable to dominate the capital of Brazil, they managed to establish themselves in Pernambuco and extended their domains over a large part of the Northeast until they were definitively expelled from the Colony in 1654.

The first Dutch attempt to conquer Salvador occurred in December 1599, when Admiral van Leynssen sent seven ships to Brazil, commanded by Captains Hartman and Broer.

The attacks in the Bay of All Saints lasted almost two months. The Dutch sink several Portuguese vessels and plunder mills in the Recôncavo. But they failed to conquer the city.

In the following years, Dutch pirates continued to attack Spanish and Portuguese ships in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In 1604, they tried again to conquer Salvador, this time with a squadron of six ships commanded by Paulus van Caerden.

The attack, similar to the first, resulted in the same failure.

In the following years, dozens of ships carrying cargo from Brazil were attacked by the Dutch.

In 1621, they founded the West India Company, a company sponsored by the Dutch government with the participation of private investors and aimed primarily at the commercial exploitation of America.

In the 16th century, Portugal had good trade relations with the Dutch, but this changed with the advent of the Iberian Union in 1580.

A year earlier, in 1579, the northern provinces of the Netherlands had formed the Union of Utrecht, a document signed by several states in the Netherlands that were struggling to gain independence from Spain.

In 1581, they formally declared their independence.

Spain, however, would only recognise it in 1648, 24 years after the West India Company decided to invade Salvador on the grounds that it felt its business in the Atlantic was being harmed by Spanish rule over Portugal.

The expulsion of the invaders in the international context

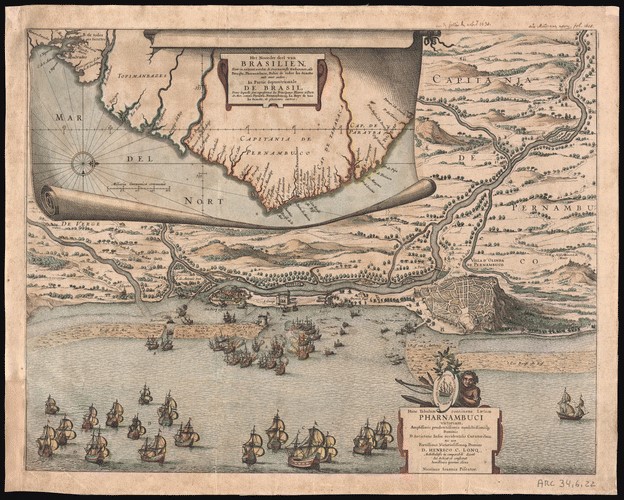

February 1630. Dutch ships and cannons once again enter Brazilian waters.

This time they invade Pernambuco, the world’s largest sugar producer at the time. They land on the coast of Pernambuco and conquer Olinda and Recife with relative ease.

The then governor Matias de Albuquerque retreated inland with men and weapons and founded the Arraial do Bom Jesus, a fortification from where the attacks on the invaders started.

As in the invasion of Bahia, the Luso-Brazilians adopted the war of ambushes in an attempt to prevent the Dutch from penetrating the lands where most of the mills were located.

Resistance, however, did not stop the Dutch advance, which even received support from local residents, such as Antônio Fernandes Calabar. The collaboration, much more than treason, was aimed at getting rid of Portuguese rule.

Defeated, Matias Albuquerque set fire to the cane fields around him and left for Alagoas. However, he managed to arrest Calabar and had him executed.

Seven years later, in 1637, the West India Company decided to rebuild the mills in order to make a profit from Brazilian sugar. To lead this project, it sent Count João Maurício de Nassau-Siegen to Brazil with the title of Governor-General.

The accumulation of wealth by the West India Company was reflected in the administration and reconstruction of Recife, the capital of Dutch Brazil. Nassau had the ability to invite a few plantation owners to participate in the administration.

He did not offer them important posts, but he did not ignore their demands. He maintained religious tolerance without forcing the Portuguese-Brazilian settlers to convert to Dutch Protestantism.

In his eagerness to understand Brazil better, Maurício de Nassau sent 46 scholars, painters and scientists from Holland to study and record the characteristics of the land, given the curiosity aroused by the rich fauna and natural beauty of the region.

The Dutch were pioneers in this type of study of Brazil.

The painters Frans Post and Albert Eckhout left beautiful paintings of the Dutch colony in the Northeast. Scientists studied tropical diseases and their possible cure.

The first astronomical observatory in the Americas was built in Recife. Maurício de Nassau also tried to give the colony greater economic autonomy so as not to be too dependent on the foreign market.

In 1640, Portugal gained independence from Spain.

In August 1645, the Luso-Brazilian settlers won an important victory at Monte das Tabocas.

The government of Bahia sent aid and Recife was besieged. The victory, however, failed to dislodge the Dutch, who were very well garrisoned by sea. The fighting continued for three years.

At the end of 1648, the Dutch suffered a major defeat in the Battle of Guararapes. Even so, Recife remains in the hands of the West India Company.

The international situation, however, helps to end the stalemate in the conflict between the Dutch and settlers in Brazil.

England declared war on the Netherlands in the dispute over the hegemony of the seas.

The English even aided the anti-Dutch rebels in Brazil.

The Portuguese rulers took advantage of the weakening of the invaders and sent a large reinforcement to the colonists in Brazil at the end of 1653. Finally, in January 1654, the Dutch surrendered.

The period of Dutch rule in Brazil was over. But it was not until 1661 that the Dutch government recognised that it no longer had any rights over Brazil.

The Dutch invasion of Salvador in 1624

Bahia.ws – Tourism and Travel Guide to Salvador, Bahia and the Northeast of Brazil