Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

Brazilian literature was born mature, expressing itself in the language of the 17th century – the baroque – and this is due to a writer from the Northeast, Gregório de Mattos.

Since Gregório de Mattos, the northeastern letters exhibit an extraordinary vigor.

The northeast region also consecrated a cultural phenomenon, the cordel, and, with the novels of Jorge Amado, made a face of Brazilian identity recognized worldwide.

If, as Haroldo de Campos believed, Brazilian literature had no childhood, that is, it was “born” mature, expressing itself in the most elaborate language of the 17th century – the Baroque – this is due to a writer from the Northeast, the Bahian poet Gregory de Mattos (1636-96).

A graduate of the University of Coimbra, with a solid cultural background, Gregório gained notoriety thanks to his relentless satirical poetry against the powerful, which earned him the nickname “Boca do Inferno”.

His work, however, was not limited to disqualifying religious and political figures – which makes it surprisingly topical. Gregório also produced lyrical and sacred verses.

The contribution of “Boca do Inferno” would be only the first of a series that the Northeast would give to national literary history – even when considering, as here, only a selection of poets and fictionists.

Literatura Nordestina - Graciliano Ramos

A contribution that is far from being restricted to the authors who emerged from modernist regionalism – such as Bahia’s Jorge Amado (1912-2000), Alagoas’ Graciliano Ramos (1892-1953) and Ceará’s Rachel de Queiroz (1910-2003), to stay with the most celebrated trio.

Romanticism marked a notable presence of Northeastern writers.

Maranhão’s Gonçalves Dias (1823-64) – inaugurating a tradition of the state’s strength in national letters – and Bahia’s Castro Alves (1847-71) became practically synonymous with poetry in the country.

Another man from Maranhão, Joaquim de Sousa Andrade (1833-1902), Sousandrade, as he preferred to be called – it is said, to have the same number of letters in his name as Shakespeare -, is a very rare case.

With the poem O Guesa (1867-88), he put Brazilian literature at the forefront of the continent. In the poem, Sousandrade takes up a Quechua legend about the sacrifice of a young man to the sun god.

He imagines the character escaping from the priests and taking refuge on Wall Street.

Also from Maranhão was the journalist and politician Manuel Odorico Mendes (1799-1864), who set himself – and won – the challenge of translating Homero and Virgil.

As a counterpoint to this erudition, it is worth remembering that it was still in the first half of the 19th century that popular poetry from the Northeast began to take shape, until it became the formidable cultural phenomenon that is cordel literature.

Born with the first private printing presses installed in Brazil and consolidated from the 1930s onwards, the cordel would establish poets such as the Ceará Aderaldo Ferreira de Araujo, Cego Aderaldo (1878-1967), and Antonio Gonçalves Silva, Patativa do Assaré (1909-2002).

In the romantic fiction practiced in the Northeast, the name of José de Alencar (1829-77) from Ceará stands out.

Like few authors, Alencar had a systematized “literary project”, which included the elaboration of a “Brazilian language” and led him to write novels of varied themes: Indianist, regional, urban, historical, etc.

Some of them are mandatory references – among them, O Guarani (1857), Lucíola (1862) and Iracema (1865).

His fellow countryman Joaquim Franklin da Silveira Távora (1842-88) believed that it was in the region of both that an “authentic” Brazilian literature could be forged, something that the South would be prevented from doing due to the large presence of foreigners.

In O cabeleira (1876) he intended to write a novel more committed to the scenarios he described.

The concern with fidelity to reality, treated objectively, would be, as we know, the nub of realism, the strand that buried romanticism and consecrated the genius of the carioca Machado de Assis. In its naturalist face, the new aesthetic emphasized the determinism of “natural laws”.

With O Mulato (1881) and especially O cortiço (1890), Maranhão’s Aluísio de Azevedo would stand out as the greatest novelist of Brazilian naturalism, which also consecrated among the northeasterners the Ceará-born Adolfo Caminha (1867-97), author of A normalista (1993) and O bom crioulo (1895).

Also from Ceará were the regionally inspired naturalists Domingos Olímpia (1850-1906), who wrote Luzia-homem (1903), and Manuel de Oliveira Paiva (1861-92), whose Dona Guidinha do Poço (1952) was published posthumously.

In the poetry that marked that period, the Parnassian, the Maranhão-born Raimundo Correia (1859-1911) would achieve a prominent place.

Before modernism, the poet Augusto dos Anjos (1884-1914), from Paraíba, would draw attention, while Graça Aranha (1868-1931), another important author of that phase, would end up going down in history mainly due to his participation in the Week of 22.

It would not be long before a particularly successful period of Brazilian literature would begin, in which regionalist fiction, especially from the Northeast, would reach a level of excellence.

The starting point for this was A bagaceira (1928), by the Paraíba native José Américo de Almeida (1887-1980), followed by O quinze (1930), by Rachel de Queiroz, Menino de engenho (1932), by José Lins do Rego (1901-57) and Caetés (1933), by Graciliano Ramos.

In 1933, the first “Bahia novel” by Jorge Amado was also released: Cacau.

Throughout his career, Jorge Amado would publish more than thirty books, translated into some fifty languages.

Often viewed with reservations, the importance of the work of Jorge Amado has gone beyond the literary sphere to a socio-cultural level.

It is undeniable that a certain section of Brazilian identity has become recognized worldwide thanks to the novels of the Bahian fiction writer.

Despite this, Jorge Amado preferred to worship his peers. When he read Caetés – in the original, lent to him by José Américo de Almeida – he took a ship to Alagoas just to meet Graciliano Ramos, in whom he never ceased to see a model writer.

Novels such as São Bernardo (1934) and Vidas secas (1938) go beyond the regionalist code. Of the former, the also fictionist Adonias Filho (1915-90), a native of Bahia, emphasized the primacy of the literary over the documentary.

And of Vidas sems we can say that it is one of the best realized books of Brazilian literature, for presenting a perfect harmony between the plot and the way of narrating it.

The overcoming of regionalism would bring out writers with more universal ambitions, commonly turned to un<intinust and experimental prose.

For example, the Pernambucan Osman Lins (1924-78), author of O Visitante (1955) and who in 1973 released Avalovara, a novel with a complex and original structure.

Two years earlier, the Paraíba-born Ariano Suassuna (1927) had made his debut in narrative prose with the publication of Romance d’A pedra do reino (1971).

In 1971, Cais da Sagração, by Josué Montello (1971), and Sargento Getúlio, by João Ubaldo Ribeiro (1941), also author of Viva o Povo Brasileiro (1982), were published.

Suassuna, who in 1977 published O Rei Degolado, a sequel to A Pedra Do Reino, has been writing the third volume of the trilogy for years.

Organizer of the Armorial Movement, which sought to combine the popular and the erudite, Ariano is a visible influence on authors such as the Pernambucans Maximiano Campos (1941-98) and Raimundo Carrero (1947).

In the same generation would stand out the Bahian Antônio Torres (1940), the Sergipe Francisco J. C. Dantas (1947). Dantas (1941) and Antonio Carlos Viana (1946) and in the following the potiguar João Almino (1950) and the cearenses Ronaldo Correia de Brito (1950) and Ana Miranda (1951) – who began his career with the poet and would only debut in the novel in 1989 with Boca do Inferno, a book inspired by, yes, himself, Gregório de Mattos.

The maturing of Northeastern fiction since modernism has seen a similar advance in poetry.

Consider the work of an author such as Pernambuco’s Manuel Bandeira (1886-1968), who brought together aesthetic freedom and metaphysical reflection in his work.

The Alagoan Jorge de Lima (1895-1953), in Invention of Orpheus (1952), surrendered to an epic dimension.

Cultivating an “objective” poetry, the Pernambucan João Cabral de Melo Neto (1920-99) created his own poetics, which, despite its formalist rigor, found space for social denunciation, as can be read in Morte e Vida Severína (1956).

The same care is present in the production of Ferreira Gullar (1930).

After dedicating himself, in The Corporal Struggle (1954), to a poetry of concretist contours, Gullar distanced himself more and more from this experience until he reached Poema Sujo (1976), in which, from political exile, he evokes, with a rare gift of verse, his native São Luís.

Killed prematurely in a plane crash, the Piauían Mário Faustino (1930-62) was an erudite critic who, in his poetry, written amidst the brilliance of the talents then active, sought to find his own way.

Finding one’s own path continues to be the proposal of the new authors from the Northeast, such as the Bahian Carlos Ribeiro (1958) and the Pernambuco Marcelino Freire (1967), whose production ratifies the vigor of a literature that, having been born already mature, as we have seen, has not aged. It remains strong, adult – great.

Writers who marked the literary history of the Northeast

Biography of Jorge Amado – Bahia

Jorge Amado (1912-2001) was a Brazilian writer. His novel “Gabriela Cravo e Canela” received the Jabuti and Machado de Assis prizes. His books have been translated into almost all languages.

He was a member of the Brazilian Academy of Literature, occupying the chair number 23. He began his writing career with works of a regionalist nature and social denunciation.

He went through several phases until he reached the phase focused on chronicle of customs. Politically committed to socialist ideas, he was arrested twice, once in 1936 and again in 1937.

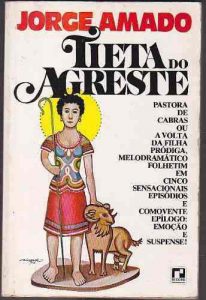

Exiled, he lived in Buenos Aires, France, Prague and several other countries with popular democracies. He returned to Brazil in 1952. Among his works adapted for television, cinema and theater are “Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands”, “Gabriela Cravo e Canela”, “Tenda dos Milagres” and “Tieta do Agreste”.

Jorge Amado (1912-2001) was born on the Auricídia Farm in Ferradas, Itabuna, Bahia, on August 10, 1912.

Son of the cocoa farmer João Amado de Faria and Eulália Leal Amado. He spent his childhood in the city of Ilhéus, where he learned his first letters. He attended secondary school at the Antônio Vieira College in Salvador.

At the age of 12, he ran away from boarding school and went to Itaporanga, in Sergipe, where his grandfather lived. He spent his teenage years among the people, becoming acquainted with popular life, which would strongly mark his work as a novelist.

At the age of 14 he began to participate in literary life, being one of the founders of the “Academia dos Rebeldes”, a group of young people who, together with the “Arco e Flecha” and the “Samba”, played an important role in the renewal of Bahian letters.

Commanded by Pinheiro Viegas, the Academia dos Rebeldes included, besides Jorge Amado, the writers João Cordeiro, Dias da Costa, Alves Ribeiro, Edison Carneiro, Valter da Silveira, and Clóvis Amorim.

In 1927, at the age of 15, he joined the “Diário da Bahia” as a reporter and also wrote for the magazine “A Luva”. At the age of nineteen he published his first novel “O País do Carnaval”. At that time he was already in Rio de Janeiro, in contact with important names in literature. He was editor-in-chief of the Rio magazine “Dom Casmurro” in 1939.

In 1933 he published his second book “Cacau”. Then came several novels that portrayed the daily life of the city of Salvador, among them “Mar Morto”, 1936 and “Capitães de Areia”, 1937, which portrays the life of juvenile delinquents, being at the time prohibited by the censorship of the Estado Novo.

Jorge Amado was married to the writer Zélia Gattai (1916-2008), who at the age of 63 began writing her memoirs.

He had two children, João Jorge, a sociologist and author of plays for children’s theater, and Paloma, a psychologist, married to the architect Pedro Costa. He is the brother of neuropediatrician Joelson Amado and writer James Amado.

He participated in the popular front movement of the National Liberation Alliance.

He was exiled in Argentina, Uruguay, Paris, Prague and lived in several countries. He received several awards, honorary titles.

He was a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences and Letters of the Democratic Republic of Germany; the Academy of Sciences of Lisbon; the Paulista Academy of Letters; and a special member of the Academy of Letters of Bahia.

He was a member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters, occupying chair no. 23.

Jorge Leal Amado de Faria died on August 6. His wake was held at the Palace of Acclamation in Salvador. He was cremated, at his request, and his ashes were placed at the foot of a mango tree, at his home in Bahia.

Works of Jorge Amado

O País do Carnaval, 1931

Cacau, 1933

Suor, 1934

Jubiabá, 1935

Mar Morto, 1936

Capitães de Areia, 1937

Terras do Sem-Fim, 1943

O Amor do Soldado, 1944

São Jorge dos Ilhéus, 1944

Bahia de Todos os Santos, 1944

Seara Vermelha, 1945

O Mundo da Paz, 1951

Os Subterrâneos da Liberdade, 1954

Gabriela Cravo e Canela, 1958

Os Velhos Marinheiros, 1961

Os Pastores da Noite, 1964

Dona Flor e Seus Dois Maridos, 1966

Tenda dos Milagres, 1969

Teresa Batista Cansada de Guerra, 1972

Tieta do Agreste, 1977

Farda Fardão Camisola de Dormir, 1979

O Menino Grapiúna, 1981

Tocaia Grande, 1984

O Sumiço da Santa: Uma História de Feitiçaria, 1988

Navegação de Cabotagem, 1992

A Descoberta da América pelos Turcos, 1994

O Milagre dos Pássaros, 1997

Biography of Tobias Barreto – Sergipe

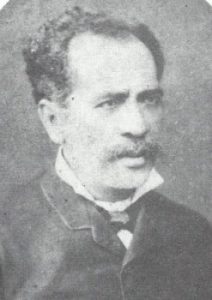

Tobias Barreto (1839-1889) was a Brazilian philosopher, writer and jurist. He was the leader of the intellectual, poetic, critical, philosophical and legal movement, known as the Recife School, which stirred the Recife Law School. Patron of chair no. 38 of the Brazilian Academy of Letters.

Tobias Barreto (1839-1889) was born in the village of Campos do Rio Real, today Tobias Barreto, in the state of Sergipe, on June 7, 1839. Son of Pedro Barreto de Menezes and Emerenciana Barreto de Menezes. He began his studies in his hometown.

In 1861 he moved to Bahia, entered the seminary, did not adapt, spent only one night. He moved to a friends’ hostel in Salvador. He studied philosophy and preparatory subjects. When the money ran out, he returned to Vila de Campos.

He lived for some years teaching Latin in Itabaiana, Sergipe.

In 1863 he moved to Recife, with the aim of entering the Faculty of Law. The atmosphere in the city was very intellectualized and dominated by students of the legal course. Among the students were Rui Barbosa, Joaquim Nabuco and Castro Alves, who became his friend.

He applied to teach Latin at the Pernambuco Gymnasium, coming second. In 1867 he applied for the position of Philosophy teacher at the same Gymnasium, was classified but not chosen.

Tobias Barreto tried to forget his humble origins, but found himself discriminated against because of the color of his skin.

He tried to marry Leocádia Cavalcanti, but was not accepted by the girl’s aristocratic family. He fell in love with Adelaide do Amaral, a Portuguese artist and married woman. He declaimed verses full of love and had poetic duels with Castro Alves.

He married the daughter of a mill owner and landowner in the town of Escada. After graduating, he spent ten years living in the small town of Pernambuco, in the sugar zone. He dedicated himself to the practice of law.

He was elected to the Provincial Assembly of Escada. He kept a newspaper, in which he printed several books.

His philosophical and scientific contribution was of great importance, since he challenged the general lines of the dominant legal thought and tried to make a link between philosophy and law, propagating the studies of Darwin and Haeckel.

Although he lived until the eve of the Republic, he did not become involved in the republican movements. He returned to Recife, where he began teaching at the Faculty of Law. Today the Faculty is known as “The House of Tobias”.

Tobias Barreto de Meneses died in Recife, Pernambuco, on June 26, 1889.

Works of Tobias Barreto

O Gênio da Humanidade, 1866

A Escravidão, 1868

Ensaios de Filosofia e Crítica, 1875

Ensaio de Pré-História da Literatura Alemã, 1879

Estudos Alemães, 1880

Dias e Noite, 1881

Menores e Loucos, 1884

Discursos, 1887

Questões Vigentes, 1888

Polêmicas, 1901

Biography of Lêdo Ivo – Alagoas

Lêdo Ivo (Maceió AL 1924) published his first book of poetry, As Imaginações, in 1944.

At the time, he was studying law at the National Law School of the University of Brazil, in Rio de Janeiro, RJ. In the following decades he published 5 novels, 14 books of essays on literature and translated poems from the works of Guy de Maupassant, Rimbaud and Dostoyevsky.

In 1957 his book of chronicles A Cidade e os Dias was published. He also wrote a novel, O Sobrinho do General, released in 1964. His poetry book Finisterra (1972) received several awards, including the Jabuti Poetry Prize in 1973.

In 1982, he received the Mário de Andrade Prize for his work as a whole, awarded by the Brazilian Academy of Letters. He was elected a member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters in 1986.

In 1991, he received the Juca Pato Trophy – Intellectual of the Year, awarded by the Brazilian Writers’ Union. Among his poetic works are Cântico (1949), Magias (1960), O Sinal Semafórico (1974), Crepúsculo Viril (1990) and O Rumor da Noite (2000).

Lêdo Ivo’s poetry belongs to the third generation of Modernism.

For the critic Carlos Montemayor, “like all the poets of his generation, Lêdo Ivo has a high awareness of language; however, his awareness is much broader, an Amazonian awareness that implies not only its involvement, but also its liberation, its eruption, its flaming explosions”.

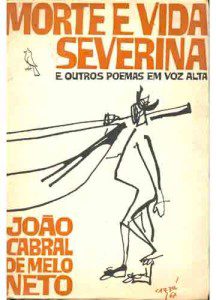

Biography of João Cabral de Melo Neto – Pernambuco

João Cabral de Melo Neto (1920-1999) was a Brazilian poet and diplomat. Author of “Morte e Vida Severina”, a dramatic poem that made him famous. He was elected a member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters.

He received the Poetry Prize from the National Book Institute, the Jabuti Prize from the Brazilian Book Academy and the Brazilian Writers Union Prize for his book “Crime na Calle Relator”.

João Cabral de Melo Neto (1920-1999) was born in Recife, Pernambuco. Son of Luís Antônio Cabral de Melo and Carmem Carneiro Leão Cabral de Melo. Brother of the historian Evaldo Cabral de Melo and cousin of the poet Manuel Bandeira and the sociologist Gilberto Freire.

He spent his childhood among the family mills in the cities of São Loureço da Mata and Moreno. He studied at the Marista College in Recife. A lover of reading, he read everything he had access to, at school and at his grandmother’s house.

In 1941, he participated in the First Poetry Congress of Recife, reading the booklet “Considerations on the Sleeping Poet”.

In 1942 he published his first collection of poems, with the book “Pedra do Sono”, where a vague atmosphere of surrealism and absurdity predominates. After becoming friends with the poet Joaquim Cardoso and the painter Vicente do Rego Monteiro, he moved to Rio de Janeiro.

During the years 1943 and 1944, he worked in the Rio de Janeiro Department for the Recruitment and Selection of Personnel. In 1945, he published his second book “O Engenheiro”, funded by the businessman and poet Augusto Frederico Schmidt.

In 1947, he entered the diplomatic career, living in various cities around the world, such as Barcelona, London, Seville, Marseille, Geneva, Bern, Asunción, Dakar and others.

In 1950, he published the poem “O Cão Sem Plumas”, from then on he began to write about social themes. In 1956 he wrote the poem “Morte e Vida Severina”, which was responsible for his popularity.

It is a Christmas carol that follows the tradition of medieval autos, making use of the redondilha, rhythm and musicality. It was brought to the stage of the Theater of the Catholic University of São Paulo (TUCA) in 1966, set to music by Chico Buarque de Holanda.

The poem tells the story of a migrant who, in order to free himself from a life of deprivation in the countryside, moves to the capital. In the big city, the retreatant is faced with a life of hardship and misery.

João Cabral de Melo Neto was married to Stella Maria Barbosa de Oliveira, with whom he had five children.

He married for the second time the poet Marly de Oliveira. He was elected a member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters, to chair number 37, taking office on May 6, 1969. In 1992, he began to suffer from progressive blindness, a disease that led him to depression.

João Cabral de Melo Neto died in Rio de Janeiro, on October 9, 1999, victim of a heart attack.

Literary Awards

José de Anchieta Award, for poetry, of the IV Centenary of São Paulo, in 1954.

Olavo Bilac Award, from the Brazilian Academy of Letters, in 1955.

Poetry Prize from the National Book Institute, in 1993.

Nestlé Biennial Award, for the body of work.

Prize of the Brazilian Union of Writers for the book “Crime na Calle Relator”, 1988.

Works of João Cabral de melo Neto

Pedra do Sono, 1942

O Engenheiro, 1945

Psicologia da Composição, 1947

O Cão Sem Plumas, 1950

O Rio, 1954

Morte e Vida Severina, 1956

Paisagens com Figuras, 1956

Uma Faca Só Lâmina, 1956

Quaderna, 1960

Dois Parlamentos, 1960

Terceira Feira, 1961

Poemas Escolhidos, 1963

A Educação Pela Pedra, 1966

Museu de Tudo, 1975

A Escola das Facas, 1980

Poesia Crítica, 1982

Auto do Frade, 1984

Agrestes, 1985

O Crime na Calle Relator, 1987

Sevilha Andando, 1989

Biography of Augusto dos Anjos – Paraíba

Augusto dos Anjos (1884-1914) was a Brazilian poet. His work is extremely original.

He is considered one of the most critical poets of his time. He was identified as the most important poet of pre-modernism, although he reveals in his poetry, roots of symbolism, portraying the taste for death, anguish and the use of metaphors.

He declared himself “Singer of the poetry of everything that is dead”.

The technical mastery in his poetry would also prove the Parnassian tradition. For a long time he was ignored by critics, who judged his vocabulary morbid and vulgar. His poetic work is summarized in a single book “EU”, published in 1912, and reissued under the name “Eu e Outros Poemas”.

Augusto dos Anjos (1884-1914) was born in the mill “Pau d’Arco”, in Paraíba. Son of Alexandre Rodrigues dos Anjos and Córdula de Carvalho Rodrigues dos Anjos. He received his first instructions from his father, a law graduate.

In 1900, he entered the Liceu Paraibano and composed his first sonnet, “Saudade”.

Augusto dos Anjos studied at the Law School of Recife between 1903 and 1907.

Graduated in Law, he returns to João Pessoa, capital of Paraíba, where he starts teaching Brazilian Literature, in private classes.

In 1908, Augusto dos Anjos was appointed to the position of professor at the Liceu Paraibano, but in 1910, he was removed from office due to disagreements with the governor.

That same year, he married Ester Fialho and moved to Rio de Janeiro after his family sold the Pau d’Arco mill. In 1911 he was appointed professor of geography at the Pedro II College.

During his life, he published several poems in newspapers and periodicals.

In 1912 he published his only book “EU”, which caused astonishment in the critics of the time, in the face of a grotesque vocabulary, in his obsession with death: rotting flesh, fetid corpses and hungry worms.

As well as for his delirious rhetoric, sometimes creative, sometimes absurd, as in this excerpt from the poem “Psicologia de um Vencido”: “I, son of carbon and ammonia,/ Monster of darkness and rutilance,/ Suffer, since the epigenesis of childhood,/ The evil influence of the signs of the zodiac”.

In 1914, Augusto dos Anjos was appointed Director of the Ribeiro Junqueira School Group, in Leopoldina, Minas Gerais, where he moved. That same year, after a long flu, he was stricken with pneumonia.

Augusto de Carvalho Rodrigues dos Anjos died in Leopoldina, Minas Gerais, on November 12, 1914.

Biography of Nísia Floresta – Rio Grande do Norte

In his book Patronos e Acadêmicos – referring to the personalities of the Academia Norte-Riograndense de Letras -, Veríssimo de Melo begins the chapter on Nísia as follows: “Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta was the most remarkable woman that the History of Rio Grande do Norte records”.

.

Indeed, Nísia’s story and work are of rare importance. “Unfortunately, the lack of dissemination of Nísia’s work has been responsible for the enormous ignorance of her unique life and her books considered of great value,” says Veríssimo.

The educator, writer and poet born on October 12, 1810, in Papari, Rio Grande do Norte, daughter of the Portuguese Dionísio Gonçalves Pinto with a Brazilian, Antônia Clara Freire, was baptized as Dionísia Gonçalves Pinto, but became known by the pseudonym Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta.

Nísia is the end of her baptismal name. Floresta, the name of the place where she was born. Brazilian is the symbol of her ufanism, a need for affirmation for someone who lived almost three decades in Europe.

Augusta is a memory of her second husband, Manuel Augusto de Faria Rocha, whom she married in 1828, father of her daughter Lívia Augusta.

That same year, Nísia’s father was murdered in Recife, where the family had moved.

In 1831, she took her first steps in literature, publishing in a Pernambuco newspaper a series of articles on the condition of women. From Recife, already widowed, with little Lívia and her mother, Nísia goes to Rio Grande do Sul where she settles and runs a school for girls.

The War of the Farrapos interrupted her plans and Nísia decided to settle in Rio de Janeiro, where she founded and directed the Brasil and Augusto schools, notable for their high level of teaching.

In 1849, on medical advice, she took her seriously injured daughter to Europe.

It was in Paris that he lived the longest. In 1853, he published Opúsculo Humanitário, a collection of articles on female emancipation, which was favorably appraised by Auguste Comte, father of positivism.

He was in Brazil between 1872 and 1875, in the midst of the abolitionist campaign led by Joaquim Nabuco, but almost nothing is known about his life during this period. She returned to Europe in 1875 and, three years later, published her last work Fragments d’un ouvrage inédit: Notes biographiques.

Nísia died in Rouen, France, at the age of 75, on April 24, 1885, of pneumonia. She was buried in Bonsecours cemetery.

In August 1954, almost 70 years later, her remains were transferred to Rio Grande do Norte and taken to her hometown, Papari, which was already called Nísia Floresta. First they were deposited in the parish church, then they were taken to a tomb in the Floresta estate, where she was born.

Her most complete biography – Nísia Floresta – Vida e Obra – was written by Constância Lima Duarte in 1995.

A book of 365 pages, edited by Editora Universitária (of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte) which, in 1991, had been presented as the author’s Doctoral Thesis in Brazilian Literature, at USP/SP.

Biography of Rachel de Queiroz – Ceará

Rachel de Queiroz (1910-2003) was a Brazilian writer.

The first woman to enter the Brazilian Academy of Letters, elected to chair No. 5 in 1977. She was also a journalist, novelist, chronicler, translator and theater writer.

She was a member of the Effective Members of the Cearense Academy of Letters. Her first novel “O Quinze” won the Graça Aranha Foundation prize. The “Memorial de Maria Moura” was transformed into a television miniseries and presented in several countries.

Rachel de Queiroz (1910-2003) was born in Fortaleza, capital of Ceará, on November 17, 1910. Daughter of Daniel de Queiroz Lima and Clotilde Franklin de Queiroz, descended on the maternal side of the family of José de Alencar.

In 1917, she moved to Rio de Janeiro with her family, who were trying to escape the drought that had hit the region since 1915. The novelist would later use the theme to write her first book “O Quinze”. Shortly afterwards, they moved to Belém do Pará, where they spent two years.

Back in Fortaleza, she entered the Colégio Imaculada Conceição, graduating as a teacher in 1925. She made her debut in journalism in 1927, in the newspaper “O Ceará”, under the pseudonym Rita de Queluz, publishing a letter ironizing the Queen of Students contest.

At the end of 1930, when she was only twenty years old, she made a name for herself in the literary life of the country with the publication of the novel “O Quinze”, a work of social background, deeply realistic in its dramatic exposition of the secular struggle of a people against misery and drought.

The book was published in only one thousand copies and already showed the characteristics that would mark his entire work. His success came with the Graça Aranha Foundation Prize in 1931.

In 1932, he published a new novel, entitled “João Miguel”. In 1937, he returned with “Caminho de Pedras”. Two years later, he won the prize of the Felipe d’Oliveira Society, with the novel “As Três Marias”. In Rio, where she lived since 1939, she collaborated in “Diário de Notícias”, in the magazine “O Cruzeiro” and in “O Jornal”.

Rachel de Queiroz published more than two thousand chronicles, which resulted in the edition of the books: “A Donzela e a Moura Torta”, “100 Crônicas Escolhidas”, “O Brasileiro Perplexo”, “O Caçador de Tatu” and “Cenas Brasileiras” (Brazilian Scenes)

In 1950, he published in pamphlets, in the magazine O Cruzeiro, the novel “O Galo de Ouro”. He has two plays, “Lampião”, written in 1953, and “A Beata Maria do Egito”, from 1958, awarded the theater prize of the National Book Institute.

In the field of children’s literature, he wrote the book “O Menino Mágico”, at the request of Lúcia Benedetti. The book, however, came from the stories she made up for her grandchildren.

Rachel de Queiroz translated more than forty works into Portuguese.

The President of the Republic, Jânio Quadros, invited her to take up the post of Minister of Education, which was refused. At the time, justifying her decision, she reportedly said: “I am only a journalist and I would like to remain only a journalist.”

She was a member of the State Council of Culture of Ceará. She attended the 21st Session of the UN General Assembly in 1966, where she served as a delegate from Brazil, working especially in the Commission on Human Rights.

She was a member of the Federal Council of Culture from its foundation in 1967 until its extinction in 1989.

She was the first woman to join the Brazilian Academy of Letters, occupying chair No. 5 on August 4, 1977. She was a member of the Effective Members of the Cearense Academy of Letters.

She was an honorary member of the Sobralense Academy of Studies and Letters and the Municipalist Academy of the State of Ceará.

In 1985, the nursery school “Casa de Rachel de Queiroz” was inaugurated in Ramat-Gau, Tel Aviv (Israel), being Rachel de Queiroz, the only Brazilian writer to have this honor in that country. She collaborated weekly in the newspaper O Povo, of Fortaleza and since 1988, she started weekly collaboration in the newspaper O Estado de São Paulo and in the Diário de Pernambuco.

Rachel de Queiroz died at her home in Rio de Janeiro of a heart attack on November 4, 2003.

Works of Rachel de Queiroz

O Quinze, 1930

João Miguel, 1932

Caminho de Pedras, 1937

As Três Marias, 1939

A Donzela e a Moura Torta, 1948

O Galo de Ouro, 1950, folhetins na revista O Cruzeiro

Lampião, 1953

A Beata Maria do Egito, 1958

100 Crônicas escolhidas, 1958

O Brasileiro Perplexo, 1964

O Caçador de Tatu, 1967

O Menino Mágico, 1969

Dora Doralina, 1975

As Menininhas e Outras Crônicas, 1976

O Jogador de Sinuca e Mais Historinhas, 1980

Cafute e Pena-de-Prata, 1986

Memorial de Maria Moura, 1992

Nosso Ceará, 1997

Tantos Anos, 1998

Três Romances, 1948

Quatro Romances, 1960

Biography of Antônio Francisco da Costa e Silva – Piauí

Antônio Francisco da Costa e Silva was born in Amarante, Piauí, on November 29, 1885.

He graduated from the Faculty of Law of Recife. He was an employee of the Ministry of Finance, having held the positions of Treasury Delegate in Maranhão, Amazonas, Rio Grande do Sul and São Paulo.

He lived not only in the capitals of these states, but also, more than once, in Belo Horizonte and Rio de Janeiro. Journalist. He retired into silence, demented, in 1933. Died on June 29, 1950.

He published the following books of poems: Sangue (1908), Zodíaco (1917), Verhaeren (1917), Pandora (1919) and Verônica (1927).

He himself organized an anthology of his verses, the first edition of which was published in 1934. Two more editions followed, the last in 1982. Three editions of his Poesias Completas were published: in 1950, 1975 and 1985.

Biography of Ferreira Gullar – Maranhão

Ferreira Gullar (1930-2016), pseudonym of José de Ribamar Ferreira, was a Brazilian poet, art critic and essayist. He paved the way for “Concrete Poetry” with the book “A Luta Corporal”.

He organized and led the literary movement “Neoconcreto”. He received the Camões Prize in 2010. In 2014, he was elected to the Brazilian Academy of Letters.

Ferreira Gullar (1930-2016) was born in São Luís, Maranhão, on September 10, 1930. He began his studies in his hometown.

At the age of 13 he began to dedicate himself to poetry. At the age of 18 he began to sign Ferreira Gullar and published his first book of poetry entitled “Um Pouco Acima do Chão”. He moved to Rio de Janeiro, where he worked as a journalist. He participated in the Popular Culture Center of the now defunct National Student Union.

Ferreira Gullar began his work under the principles of concrete poetry, but soon left the avant-garde of São Paulo, in a struggle to build an expression of his own. In 1954 he wrote “A Luta Corporal”, a book that foreshadowed Concrete Poetry.

In 1956, after participating in the first Concrete Poetry exhibition, held in São Paulo, he organized and led the “Neoconcrete” group, in which Lígia Clark and Hélio Oiticica participated.

After breaking with the concretists, he approached popular reality and the progressive thinking of the time, all of it linked to populism.

Ferreira Gullar was president of the UNE Popular Culture Center when the military coup took place in 1964. Affiliated to the PC and one of the founders of the Opinião group, he was arrested and lived outside the country from 1971 to 1977. He was exiled in Paris and then in Buenos Aires.

In 1976, he published the “Poema Sujo”, written in 1975, in exile in Buenos Aires, which represents the solution to the problems experienced by all the intellectuals of the period, who saw their populist ideals suffocated by the 1964 revolution.

In 1977 he was acquitted by the Supreme Court and returned to Brazil.

For the theater, Ferreira Gullar wrote, in 1966, in partnership with Oduvaldo Vianna Filho, the play “Se Correr o Bicho Pega, Se Ficar o Bicho Come”. In partnership with Arnaldo Costa and A.C. Fontoura, he wrote, in 1967, “A Saída? Where is the Exit?”.

Together with Dias Gomes, in 1968, he wrote “Dr. Getúlio, Sua Vida e Sua Glória”. For television, he collaborated for the soap operas Araponga in 1990, Irmãos Coragem in 1995 and Dona Flor e Seus Dois Maridos in 1998.

Ferreira Gullar won several literature awards, including the Jabuti Prize for Best Fiction Book in 2007, with “Resmungos”. He was also recognized with the Camões Prize in 2010. In the same year, he received the title of Doctor Honoris Causa, from UFRJ. In 2011, he received the Jabuti Prize for Poetry.

On October 9, 2014, Ferreira Gullar was elected to chair number 37 of the Brazilian Academy of Letters.

In December of that same year, he held the exhibition “A Revelação do Avesso” (The Revelation Inside Out), where he presented 30 paintings made from collages with colored paper, which were produced as a hobby.

The exhibition was accompanied by a book with photos of the complete collection and also with poems by the author.

Ferreira Gullar died in Rio de Janeiro on December 4, 2016.

Works by Ferreira Gullar

Um Pouco Acima do Chão, poesia, 1949

A Luta Corporal, poesia, 1954

Teoria do Não-Objeto, ensaio, 1959

João Boa-Morte, Cabra Marcado pra Morrer, poesia, 1962

Quem Matou Aparecida?, poesia, 1962

Cultura Posta em Questão, ensaio, 1964

Se Corre o Bicho Pega, Se Ficar o Bicho Come, teatro, 1966

A Saída? Onde Fica a Saída?, teatro, 1967

Dr. Getúlio, Sua Vida e Sua Glória, teatro, 1968

Por Você, Por Mim, poesia, 1968

Vanguarda e Subdesenvolvimento, ensaio, 1969

Dentro da Noite Veloz, poesia, 1975

A Luta Corporal e Novos Poemas, poesia, 1976

Poema Sujo, poesia, 1976

Antologia Poética, poesia, 1977

Augusto dos Anjos ou Vida e Morte Nordestina, ensaio, 1977

A Vertigem do Dia, poesia, 1980

Sobre Arte, ensaio, 1983

Barulhos, poesia, 1987

Poemas Escolhidos, 1989

Indagação de Hoje, ensaio, 1989

O Formigueiro, poesia, 1991

Argumentação Contra a Morte da Arte, ensaio, 1993

Rabo de Foguete-Os Anos no Exílio, memórias, 1998

Muitas Vozes, poesia, 1999

Rembrandt, ensaio, 2002

Relâmpagos, ensaio, 2003

Um Gato Chamado Gatinho, poesia, 2005

Resmungos, poesia, 2007

Em Alguma Parte Alguma, poesia, 2010

Autobiografia Poética e Outros Textos, 2016

History and origin of Northeastern literature

Biography of the main authors of the northeast

Bahia.ws – Tourism and Travel Guide to Salvador, Bahia and the Northeast