Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

Rio de Contas is one of the oldest cities in the Chapada Diamantina region.

With preserved baroque architecture from the 17th century, Rio de Contas was the first planned city in Brazil, in 1745, during the heyday of gold that seemed inexhaustible.

Rio de Contas is home to communities of Portuguese descendants who only intermarry.

They are at 1500m (above sea level); the two black communities of African descent are in another area, at 1050m.

The municipal historical archive of Rio de Contas has interesting documents, such as letters of manumission, ecclesiastical sentences and slave certificates.

The rich flora prompted more than 100 English and Brazilian researchers to conduct a study of the local variety in 1974. More than 1100 species were recorded and more than 100 unknown.

Video about Rio de Contas BA

RIO DE CONTAS - SUA HISTÓRIA08:57

História de Rio de Contas08:39

Rio de Contas Guia de Turismo

Rio de Contas Patrimonio Nacional

Rio de Contas na Chapada Diamantina

Rio de Contas Dicas de Viagem

Rio de Contas Guia de Viagem07:48

Rio de Contas - Drone12:01

Igreja de Santana em Rio de Contas25:49

AS BELEZAS E A HISTÓRIA DE RIO DE CONTAS

Film “Behind the Sun”

Rio de Contas was the setting for the movie “Behind the Sun”, directed by Walter Salles (the same director of Central do Brasil), the filming took place between August and September 2000.

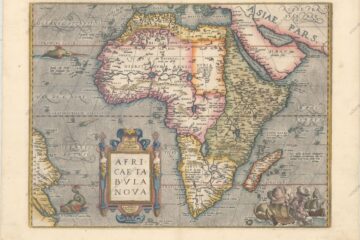

View the map Chapada Diamantina

History of Rio de Contas

The colonization of the region began at the end of the 17th century, when escaped slaves settled on the left bank of the Contas Pequeno River, where the current city of Brumado emerged, which soon became a landing point for travelers from Minas Gerais and Goiás who were heading towards Salvador.

As there was a path that connected the São Francisco River Valley to the coast, they founded the village of Creoulos. A chapel was built on this site, under the invocation of Our Lady of Santana, whose foundations still existed at the beginning of the 20th century.

Going up the river Brumado, Sebastião Raposo, from São Paulo, discovered gold in the 1710s, and the settlement of Mato Grosso arose near the mine, where, according to tradition, the Jesuits built the Church of Santo Antônio.

In 1715, the same Paulistas founded a settlement downriver where the Chapel of Our Lady of Deliverance was built. In order to prevent the evasion of the “quinto” (a tax levied by Portugal on the gold extracted) and to control disorder, the Count of Sabugosa commissioned the Bahian explorer Pedro Barbosa Leal to found villages in the region.

The town grew as a result of mining and, in 1718, the parish of Santo Antônio de Mato Grosso was created, the first in the highlands of Bahia. At that time, the Jesuits built a church, 12 kilometers below the village of Creoulos, dedicated to Our Lady of Livramento.

In 1724, Viceroy Dom Vasco Fernandes commissioned Colonel Pedro Barbosa Leal to create the town of Nossa Senhora do Livramento do Rio de Contas.

In 1726, it was decided to establish foundry houses in the region.

The discovery of auriferous veins and gravel attracted São Paulo bandeirantes to the region, and the discovery of mines in the region favored the occupation of this stretch of the plateau when, in 1745, the old village was transferred to the new site, called Vila Nova de Nossa Sra. do Livramento e Minas do Rio de Contas.

The transfer of the town was due to the need to better control the alluvial gold mines.

The stagnation of Rio de Contas began in 1800 with the fall in gold production, and worsened in 1844 with the emigration of a large part of the population to the newly discovered diamond mines in Mucugê. But the town did not exactly fall into decay.

The creation of the Casa de Fundição brought to the town the technique of jewelry making, generating an artisanal metallurgy, which became the basis of the local economy.

It is not without reason that the largest collections of the “quinto” were recorded in the years immediately following the creation of the town of Rio de Contas. Rich in alluvial gold, the municipality extended its boundaries to the state of Minas Gerais and grew rapidly.

The discovery of gold in the bed of the Brumado River attracted a large number of prospectors to the region who, going up the river, founded the settlement called Mato Grosso.

Even with the decline in gold production, Rio de Contas continued to be an obligatory stopover on the Camino Real, which led from Cachoeira to Goiás and Mato Grosso, and through which the pilgrimages of the religious to Bom Jesus da Lapa passed. During the 19th century, all traffic to the southwest of the São Francisco River Basin was made by this route.

In 1868, the district of Vila Velha was created, annexed to the village of Minas do Rio de Contas, and elevated to the status of city with the name of Minas do Rio de Contas, in 1885. In 1931, the municipality of Minas do Rio de Contas was renamed Rio de Contas.

When the deposits began to run out, handicrafts and agriculture based on coffee, sugar cane, cereals and tubers developed. In the 20th century, new gold rushes occurred in 1932 and 1939.

Tourist Attractions of Rio de Contas

1. Pico das Almas with 1958m

One of the highest in Chapada Diamantina. Those who enjoy climbing, see the peak as another possibility of adventure. Three days with camping in the ecological sanctuary of Largo do Queiroz and trekking through streams and forests where the Brumado River rises are already rewards before reaching the summit.

2. Igreja Nossa Senhora de Santana

Igreja Nossa Senhora de Santana was built by slaves, it remained in ruins for about 50 years, which facilitated the removal of

stones for the construction of some neighboring houses. The characteristic of the construction, according to architects, seems to date from the 19th century. After the listing some things like the roof were rebuilt.

3. Flora

The region presents species not yet identified or cataloged. The diversity concerns decorative species (cinnamon trees, orchids, bromeliads, cacti and evergreens), food and medicinal species.

4. Zofir Museum

In the house where the artist Zofir Oliveira Brasil (1926-1990) lived, the curious works made with wood are exhibited recycled and scrap material. At the entrance to Rio de Contas is a painted stone, the Negra do Zofir.

5. Barbado Peak

2033m, the highest peak in the Northeast and geological formation of rare beauty. It is an environmental protection area due to its botanical richness.

6. Estrada Real

pedestrian road. Paved in stone slabs that connected Rio de Contas to the city of Livramento. The route provides all the beauty of the descent of the mountains.

7. Old House of Chamber and Jail

one of the most feared prisons in Bahia at the time of slavery. To this day, there are instruments that were used to torture slaves, as well as a coat of arms of the empire on its façade.

8. Municipal Archive

House where the Baron of Macaúbas (Abílio de César Borges) was born. The site has documents that record the past of the region since 1724. Letters of freedom, ecclesiastical sentence and slave certificates, among others, are part of the collection.

9. Fraga Waterfall

Waterfall in the Brumado River. It forms natural pools great for swimming.

10. Colonel’s Bridge

Nothing more, nothing less than 8 natural pools!

11. Poço das Andorinhas (Swallows Well)

Located in the district of Arapiranga, 25 km from the municipality’s headquarters. The well is located on top of a mountain, where it is reached by a steep road that can be overcome on foot or in a 4×4 vehicle, on a 6 km route.

The trail is intersected by waterfalls and natural pools of crystal clear water.

Best time to visit

From December to March, the rainy season, when the water flow is higher, thus providing better waterfall baths, in addition to making the flora much greener.

Travel and Tourism Guide of Rio das Contas in Chapada Diamantina

Main events in Rio de Contas

- February

The most traditional carnival of the Chapada Diamantina takes place in Rio de Contas. Mask contests, washing of the Santana Staircase and a party in the Praça da Matriz are part of the revelry.

- May and June

Feast of the Patron Saint: Blessed Sacrament (Corpus Christi).

Celebrated for over a century. Highlight for the eve of the party with the night of the lanterns and the traditional auction in the churchyard, and on the day of the party the procession with the houses decorated with lace and crocheted towels in the windows, streets carpeted with flowers, rice husks, saw dust, formed drawing allusive to the festivities. Presentation of the Philharmonic Lira dos Artistas.

Climate & Temperature in Rio de Contas

Dry and hot climate in the lowlands / temperate or cold in the highlands and in the general. The temperature varies from 7ºC to 32ºC.