Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

The Poti River canyon is one of the natural features of the State of Piauí, located more characteristically in the municipalities of Buriti dos Montes, Castelo do Piauí and Juazeiro do Piauí, with two access routes: one from Juazeiro do Piauí and another from Castelo do Piauí.

The Poti River, so named since 1760, was born Itaim-Açu, along which farms donated as sesmarias by the Portuguese crown were installed in the 18th century.

The Poti River runs for more than 80 km northwards through Ceará until it is captured by a fault system of the Transbrasilian lineament, deepening its bed as a result of the mechanical action of the waters on sediments of the Cabeças Formation,

predominantly.

The Transbrasilian Lineament cuts through Brazil from Sobral to Mato Grosso.

The river cuts through the Ibiapaba mountain system and the stretch between Cachoeira da Lembrada and Pedalta Canyon is where the Poti River Canyon is established, although its bed is also steep for other stretches until its mouth in Teresina.

The best time to visit the region is after the rains between July and December.

The place is suitable for practicing adventure sports such as abseiling, canoeing, cycling and trekking.

The source of the Poti River is located at Fazenda Jatobá, in the municipality of Quiterianópolis, Ceará.

The Poti River basin, due to its geographical position and the canyon, functioned as a migratory corridor between the plains of Piauí and Maranhão and the semi-arid region of Ceará, Pernambuco and Bahia.

The thousands of rock carvings, made in low relief by pricking, and many other rock paintings in shelters under rocks prove that this region was once a millennial migratory route of the first inhabitants of the Americas.

These are some of the reasons for tourists to fall in love with the beauty of the canyon.

The landscape, the ancestral trail, the rock inscriptions, the transitional vegetation between the caatinga, the carrasco and the cerrado; the white, yellow and red of the sandstone walls, as well as the whole work, accredits the formidable boqueirão to be among the most radical and beautiful ecotourism routes in Brazil.

The long natural history of the Poti River Canyon, between Ceará and Piauí.

About a hundred million years ago, South America and Africa, which were part of the megacontinent Pangea, split.

The Brazilian Northeast was the last part of this territory to be separated, and almost individualized as a separate continent. This did not happen, but the land suffered great efforts, was deformed, failed, fractured.

The great mark of this episode of continental separation in the Brazilian Northeast was the uplift of the land in the interior of the continent: crystalline land and sedimentary were thrown upwards, raised to an altitude perhaps not much higher than the top of the highest reliefs of today (about a thousand meters).

Since then, the relief, the natural landscapes, have evolved from the erosion of this uplifted surface, commanded by dry climates – that is, erosion is not very intense, because there is a lack of water to “destroy” the rocks.

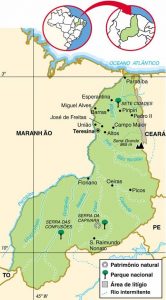

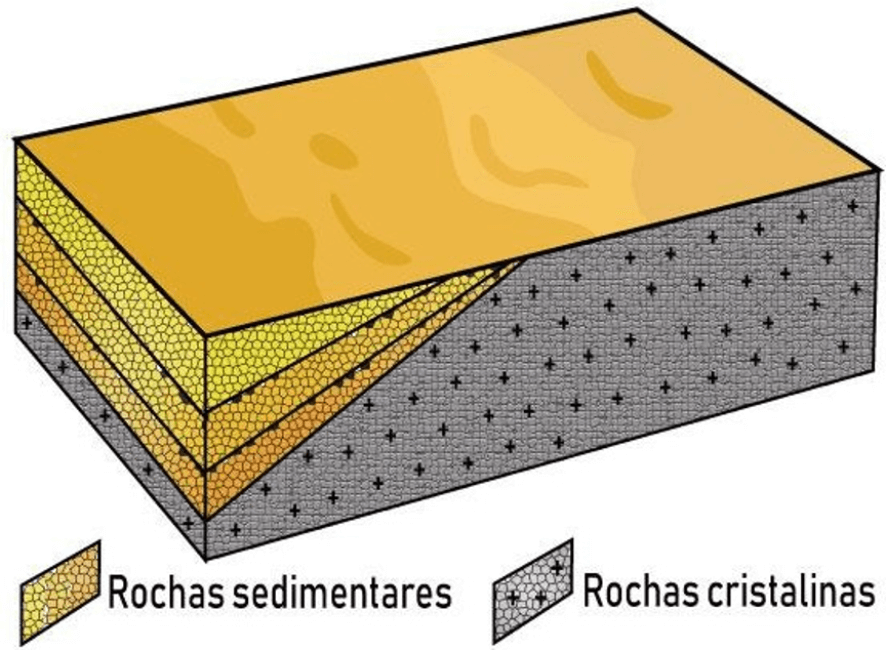

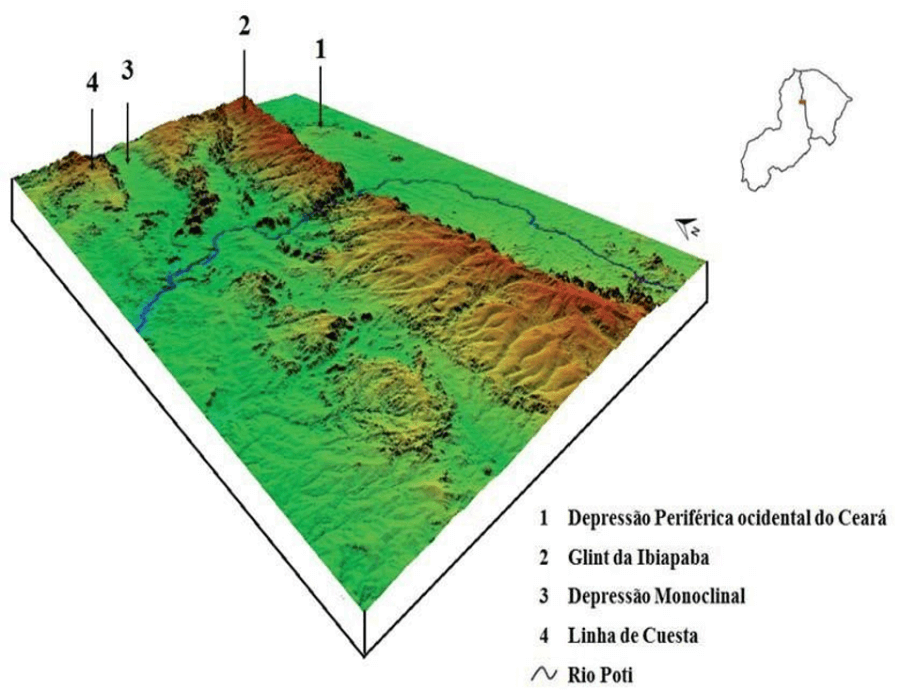

In the western segment of the State of Ceará, in the area that today corresponds to the border with the State of Piauí, this uplift placed sedimentary soils (the sandstones of the Sedimentary Basin of the Ceará State); Parnaíba Sedimentary Basin, very old, about 430 million years old) and crystalline terrains also old (2.2 billion years old, formed by gneisses and other metamorphic rocks) side by side (Figure 1).

As soon as this happened, the rivers, which are the greatest sculptors of the Earth’s surface, taking advantage of topographic unevenness on the uplifted surface, began to dig their valleys. Among these rivers was the ancient Poti River, which rises in the Serra dos Cariris Novos, in the municipality of Quiterianópolis, located south of Crateús (CE).

It drains from south to north until the height of Crateús, where it flows in an east-west direction, to flow into the Parnaíba River, in Teresina, PI. It has a length of approximately 570 km.

The Poti River began to dissect the sedimentary and crystalline terrains around 90, 80 million years ago. Coming from south to north, it found a geological fault (area of rupture between rocks) in these terrains, fit into the fault, and then began to flow from east to west.

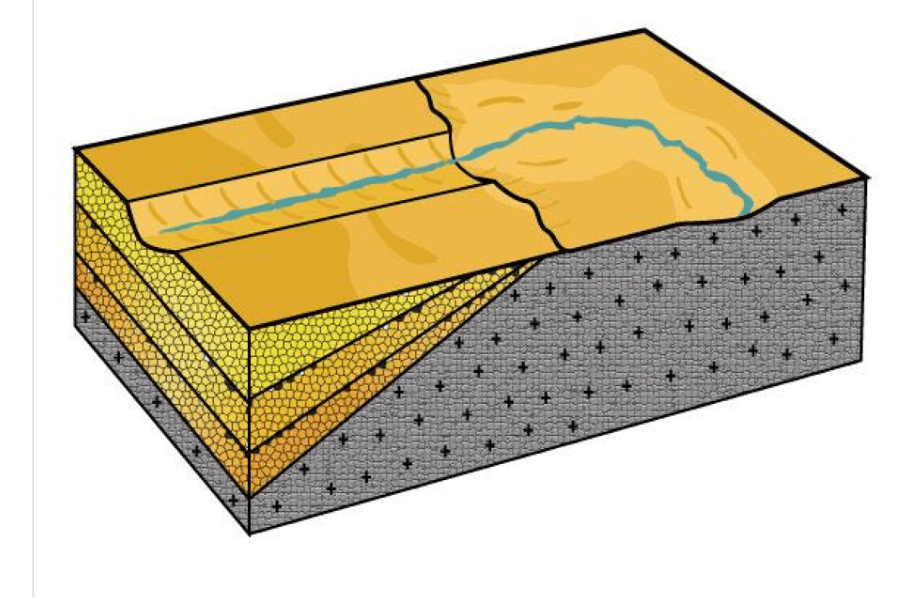

The great surprise that nature gave the Poti River was this: it quickly “realized” that sedimentary rocks were more resistant to the digging process than crystalline rocks. Thus, the river was opening the valley more easily in the crystalline terrains, while in the sedimentary terrains, resistant, the valley that was being opened was of the throat type (Figure 2).

Over the millions of years, the digging of the old Poti River followed this logic: it dug more into the crystalline than into the sedimentary.

While digging in the crystalline, the river was deepening the valley in the sedimentary, so that the river bed was always at the same level of topographic height. Several tributaries emerged on the crystalline side, and helped in the process of widening the valley.

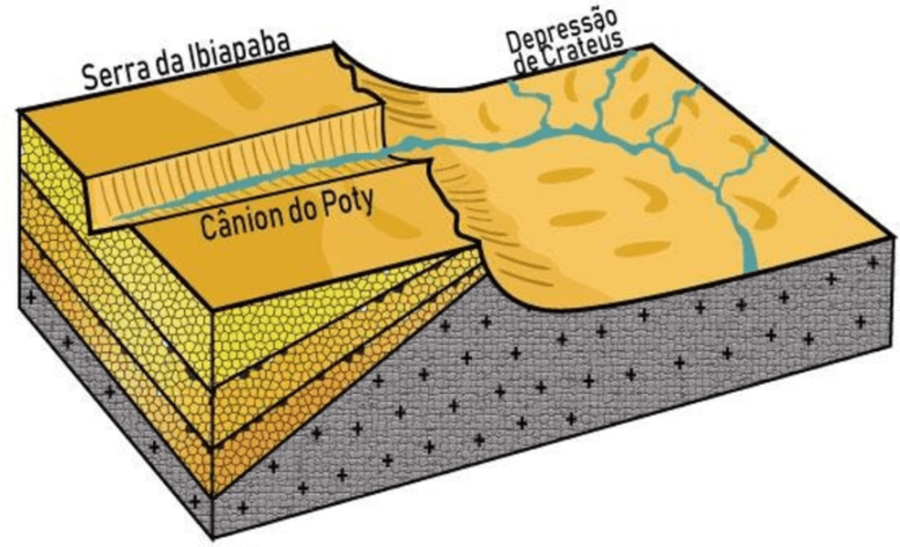

The result of this long evolutionary history was that a depressed area emerged in the crystalline, while the sedimentary was getting a rebound (Figure 3).

As these erosive processes evolved over time, the result was the formation of the Poti Canyon, the emergence of the Serra da Ibiapaba (which represents the uneven contact, the rebound, between crystalline and sedimentary) and the formation of a large lowered area at the foot of the Ibiapaba, which corresponds to what we call the sertão.

The logic of the existence of the Poti Canyon, the Ibiapaba Mountains and the sertão (the current floor surface) is therefore one, the so-called “differential erosion”: the most resistant materials were little eroded, in the form of a canyon (canyon) or elevation (Ibiapaba Mountains), and the most fragile material was lowered and depressed (the sertão) (Figure 4).

Thus ends our story. From now on, the tendency is for this evolutionary process to advance, with a retreat to the west of the Serra da Ibiapaba and eventual collapse of the canyon walls in the future (millions of years). That is, if society does not change the course of evolution.

We have to hope that they never think of making a dam on the river downstream of the canyon, as happened in similar situations in other areas of the world and in our own country. Let’s take care of the survival of our canyon.

The little map made from topographic data shows the current situation (Figure 5).

Poti River Canyon reveals beauty of mountain range between Piauí and Ceará