Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

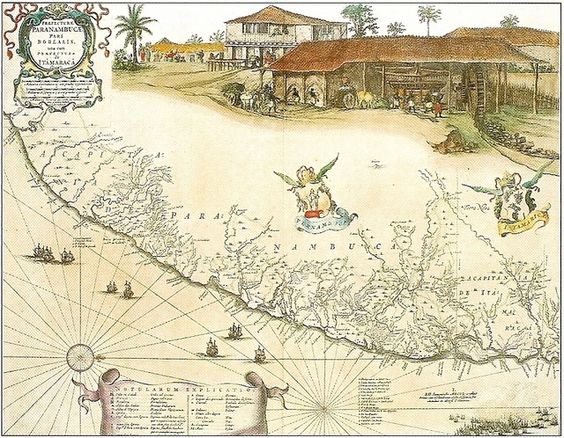

Recife dos Holandeses began with the Dutch invasion that was part of the Dutch project to occupy and administer the Brazilian Northeast through the Dutch West India Company.

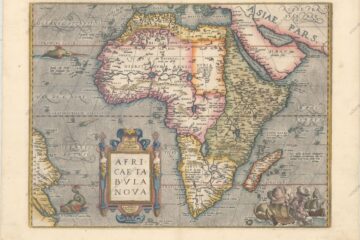

In 1624 the Dutch had already created the West India Company and started plans for the expansion of their overseas domains in Africa and America, since the East India Company was, at the time, relatively successful in Asia.

But how to conquer places already occupied and colonized by the Portuguese and Spanish, even more so at the time of the Iberian Union?

The way was to use force. And so the Netherlands managed to control Salvador, then the capital of Brazil, for about a year.

For the Dutch, the important thing was to traffic slaves to the northeastern plantations and eliminate the middlemen – in this case, the Iberians – in the sugar trade.

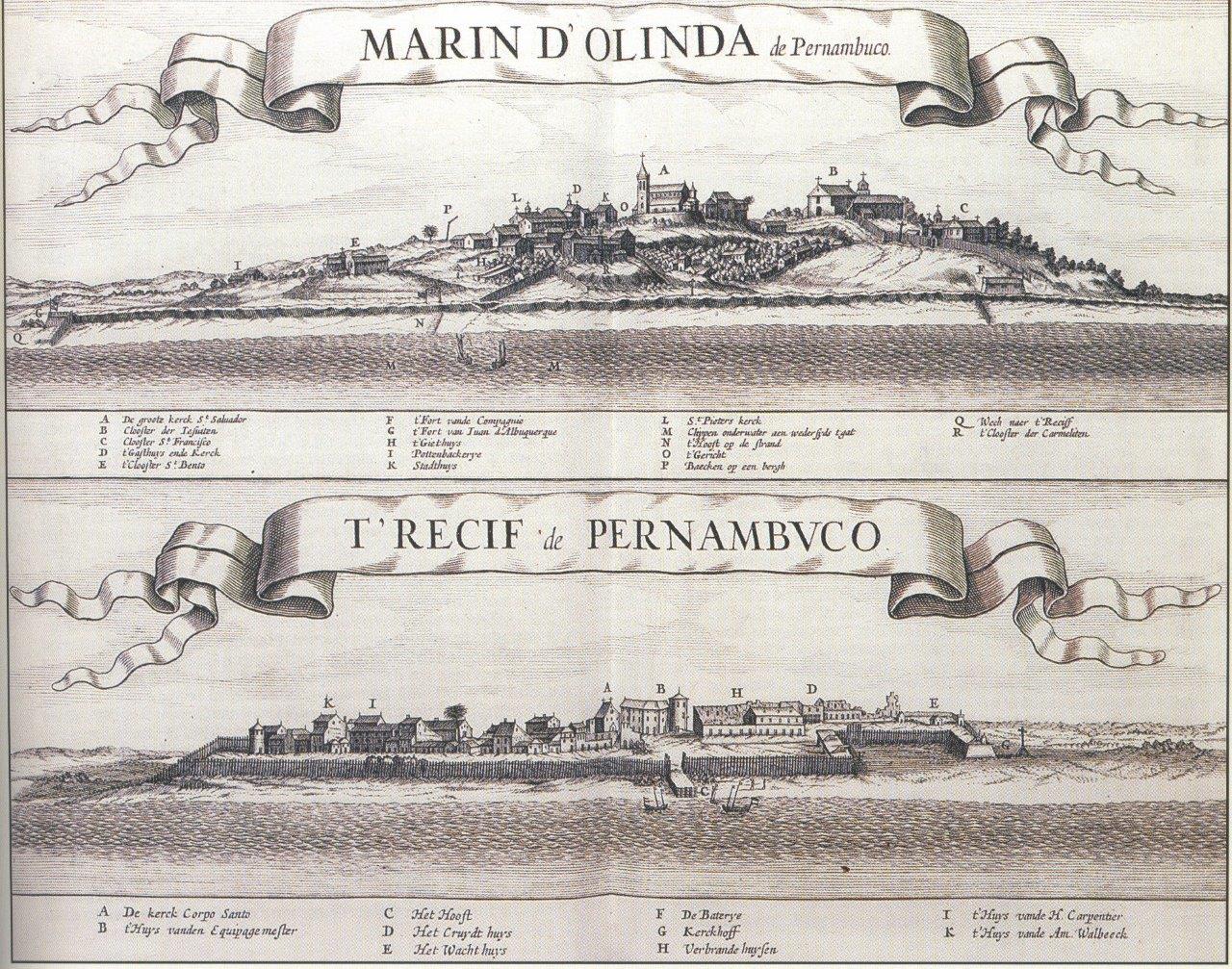

Expelled by the Jornada dos Vassalos in 1625, the Dutch joined forces for five years and in 1630 conquered Olinda and Recife.

And this is where we begin our text, talking about the Dutch influence in the region in twenty-four years of domination.

Conquering Olinda, then Recife: The lack of Portuguese defenses was decisive for the Dutch success.

History of the Dutch Invasion in Recife

História de Recife dos Holandeses

Invasão holandesa no Brasil

Legado holandês e o mito de Maurício de Nassau25:49

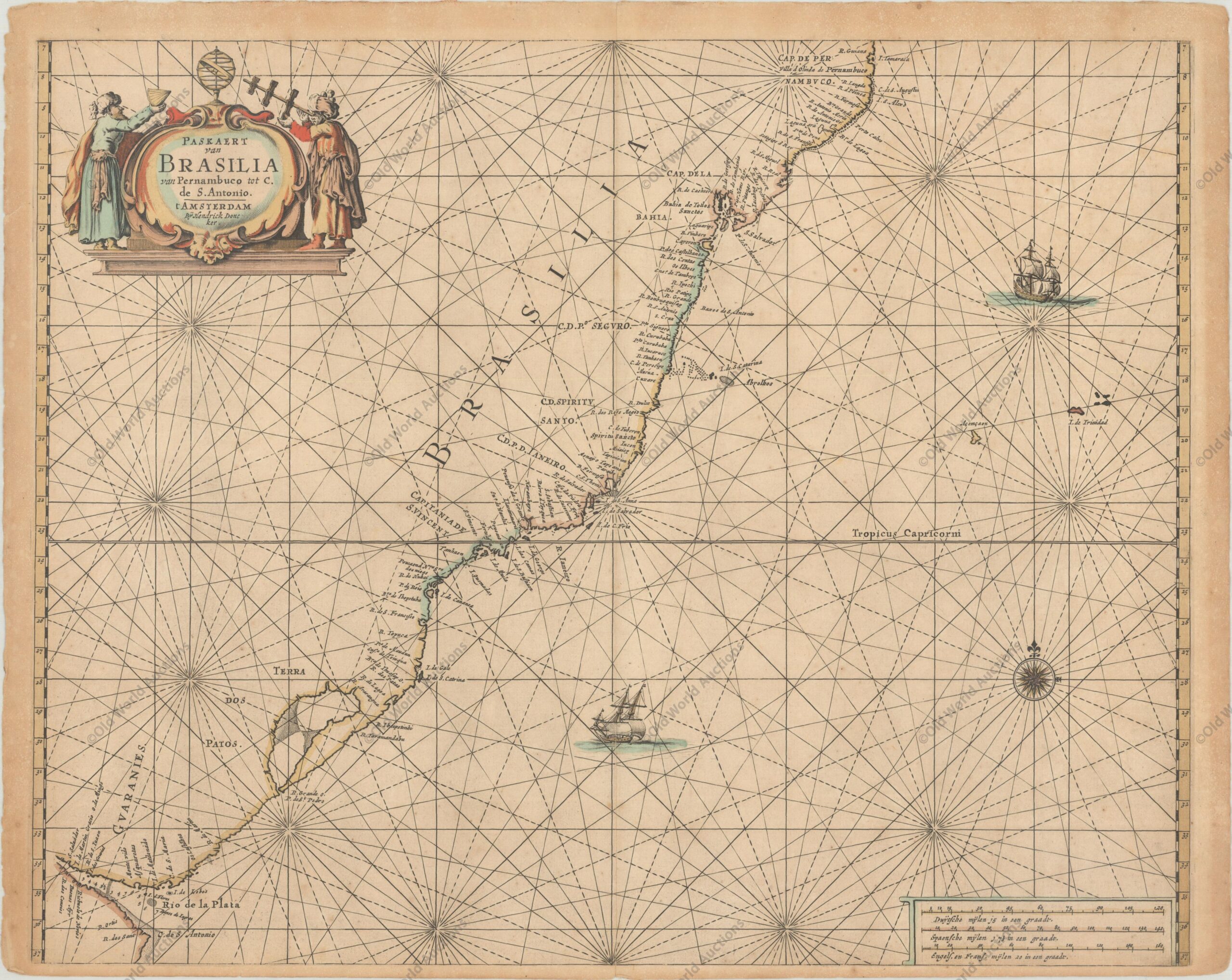

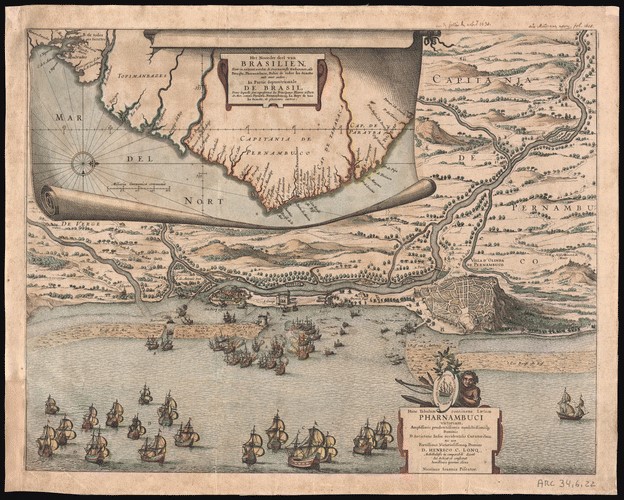

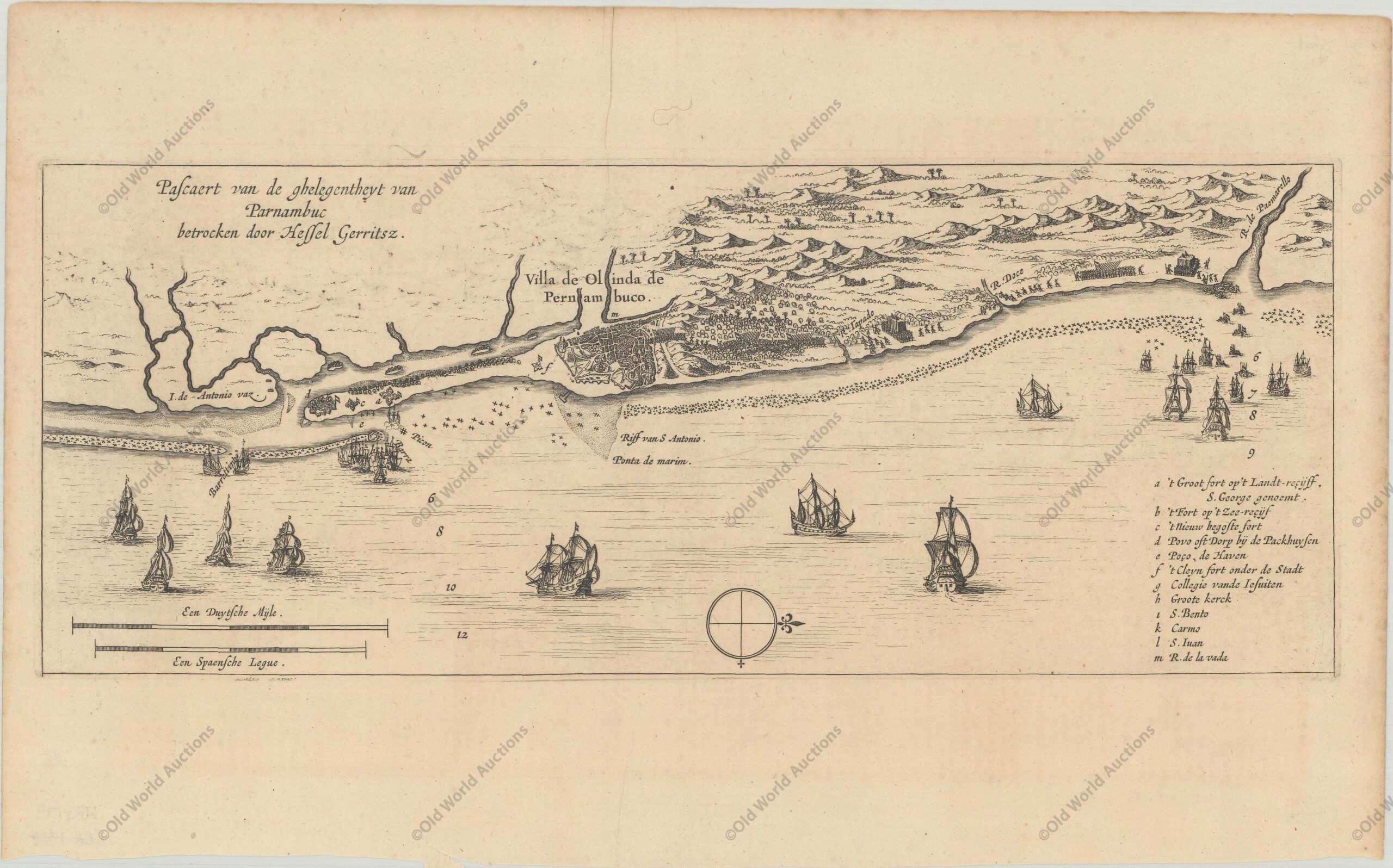

In February 1630 (in 1654 the Dutch left Brazil for good), 56 Dutch ships with 3780 crew and 3500 soldiers commanded by Diederik van Waerdenburch arrived in Olinda.

They quickly took the city, as there was not much Portuguese resistance available.

They then headed for Recife and after also conquering the city, they received the reinforcement of about 6,000 men sent to help defend the conquered area and expand their domains. But the Portuguese response was not long in coming.

Matias de Albuquerque, brother of the donatory Duarte de Albuquerque Coelho – the Count of Pernambuco – organized an offensive against the Dutch the following year, supported by a squadron of 23 Spanish and Portuguese ships.

His greatest merit was knowing how to use the support of the natives and his guerrilla tactics to expel the Dutch from Olinda, who chose to leave the city and concentrate all their defense in Recife.

By controlling Recife, the Dutch began to traffic the slaves brought from Africa and sell them to the mill owners of Pernambuco – a captaincy that was the main producer of sugar and tobacco at the time – in addition to trading with the mills in the region, since the port of Recife was the main exit door for Pernambuco products.

The dominated territory even had its own flag, since the Dutch considered the conquered regions as the “New Netherlands”.

After this retreat and a time without being able to leave Recife, the Dutch tried to conquer nearby coastal regions – in Paraíba in 1634 and in Rio Grande do Norte in 1635 – and were relatively successful, relying mainly on the help of Domingos Calabar, who is considered by many to be a traitor to the Portuguese crown by reporting to the Dutch various details of the cities and fortifications where the Portuguese defended themselves.

What many do not consider is that the region’s sugar producers themselves came to like Dutch domination, as there was an almost immediate injection of capital into the business, and the more liberal Dutch way of trading was more profitable for producers.

In 1637, aiming at the definitive administrative consolidation of the region, the Netherlands sent to Brazil the one who would become the main character in this occupation, Count Maurício de Nassau.

The Capital of Dutch Brazil

Nassau promoted important changes in the “New Netherlands”

Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen, better known to Brazilians as Maurício de Nassau, held the position of governor, captain and admiral general of Brazil on behalf of the West India Company.

A skilled negotiator, he always sought to reconcile Dutch interests with local merchants and mill owners, regardless of their nationality, and to end disputes with the Portuguese, since the struggles that were still being fought, even if isolated, caused losses for both local producers and the Dutch.

To this end, Nassau ordered that new territories be occupied. Thus, parts of Sergipe and Maranhão were conquered by the Dutch.

The count also created the Chamber of Escabinos, along the lines of the Municipal Councils of the time, with the function of legislating and also judging cases in the first instance still in the colony.

But it was in urban, cultural and religious terms that Nassau left his name forever marked in Brazil.

– Urbanization of Recife

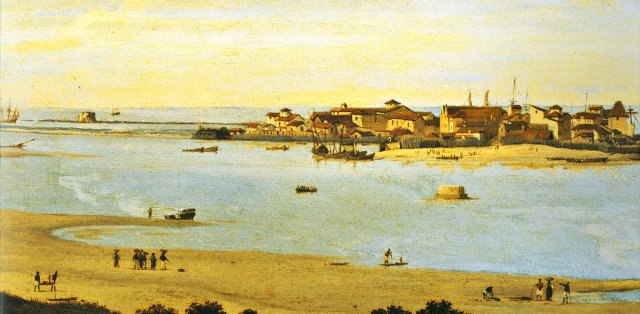

The architect Pieter Post designed the layout of Mauritstad, or “Mauritius City”, which today includes the neighborhoods of Santo Antônio and São José in Recife.

Bridges, canals, dykes and buildings were built, as well as the Freeburg Palace, seat of Nassau’s government.

The botanical garden, the natural museum and the astronomical observatory, the first in America, were also built.

Other architects and engineers assisted in the urbanization of Recife, focusing mainly on basic sanitation. Nassau also ordered the creation of a garbage collection service and a fire department.

It is also from this time the construction of several forts by the sea, such as Fort Brum and Fort Orange, aiming at the defense of the occupied areas.

– Cultural expedition

Nassau brought a number of scientists to Brazil, including the physician Willem Piso and the mathematician, astronomer and naturalist Georg Marcgraf, who studied the local fauna, flora and diseases.

The Historia Naturalis Brasiliae, which can be considered the first scientific work on Brazilian nature, was written by both of them.

Also in the entourage were landscape artist Frans Post – brother of architect Pieter Post – and portrait painter Albert Eckhout.

The painting opposite, “African Woman”, is by Eckhout, who also painted several canvases depicting the natives and African slaves who lived in the region.

The expedition sponsored by Nassau also included the cartographer Cornelis Golijath and the humanist Caspar Barlaeus.

It is unnecessary to list here the importance of the coming of these scientists and artists to Brazil at a time when the European metropoles already enjoyed a relative cultural advance while the colonies received very little attention in these aspects.

Much important information about our country during the colonial period was produced by this and other expeditions that brought European scholars to Brazil.

Unlike the first Portuguese who came to Brazil to settle and produce in the Hereditary Captaincies, the Dutch did not expect only to trade with the people who lived here, but also to develop the conquered region.

– Religious tolerance

Nassau was a Calvinist and yet he made no restrictions on the Catholicism already entrenched in the region by the Portuguese. In addition, he encouraged the arrival of Jews of Portuguese origin refugees in the Netherlands to the “New Netherlands”.

Even with the guarantee of freedom of worship by the Nassau government, there was a certain anti-Semitism in the region, motivated mainly by the Portuguese. In Recife was founded the first synagogue of the Americas, the Kahal Zur Israel.

For those who are more interested in knowing about the Dutch contributions, I advise you to visit the website of the Recife City Hall, which contains other interesting data.

But when reading about the time when the Dutch controlled part of the Brazilian territory, the thought immediately comes to mind: “What would these regions be like today if the Netherlands controlled them longer?”

Unfortunately we can only imagine, because Nassau left the administration of Recife in 1644, dissatisfied with the interference of the West India Company over the territory.

The new administrators who came to Brazil ended up provoking the Pernambuco Insurrection.

The “War of Divine Light”

Out with the Dutch!

A certain bearded German once said that everything in history can be summed up in economic – or production – relations. With all due respect, we can say that Brazilian merchants and producers provoked the Pernambucan Insurrection because they started losing money.

The Dutch who replaced Nassau in the administration of New Holland practically tore up the Count’s political will and began to collect from the sugarcane producers the debts they had contracted with the Dutch.

Not that the growers didn’t pay, but apparently everything was collected at a time when the weather didn’t help much and the cane and tobacco crop was very poor, causing losses for both sides.

The main leaders who fought against the Dutch were: the mill owner João Fernandes Vieira; the soldier André Vidal de Negreiros – named Master-in-Camp during the fighting – and the soldier Antonio Dias Cardoso, today patron of the 1st Battalion of Special Forces of the Brazilian Army; the native Felipe Camarão, better known as Potiguaçu, who led several guerrilla actions; and the black Henrique Dias, who commanded several former slaves who fought together with the Portuguese and Brazilians for the liberation of the region.

The Pernambuco Insurrection is considered by the traditional Brazilian military historiography as the first patriotic movement in Brazil and featured very violent fights, such as the Battle of Guararapes, portrayed in the painting above, by Victor Meirelles, painted only in 1789.

In 1654 the Dutch left Brazil for good, although a definitive peace treaty was only signed in 1661, after part of the Dutch armada threatened Lisbon demanding payment of compensation for the loss of territories.

Recife of the Dutch