Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

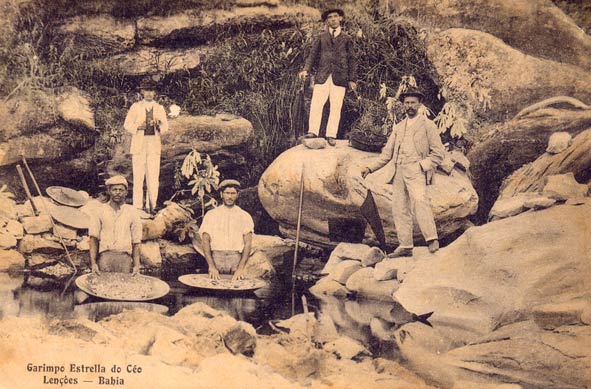

Mining and garimpo were the great economic engines of Chapada Diamantina centuries ago.

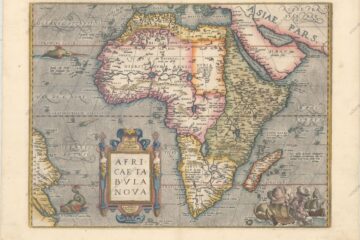

First gold, found in the 18th century in Rio de Contas and Jacobina, then diamond, whose first deposits were discovered in the early 19th century in Mucugê.

Many of the towns of the Chapada da Diamantina retain in their houses the memory of those golden times. For almost the entire 19th century, Bahia was the largest diamond producer in the world.

When the South African mines were found in 1870, production declined and was only saved by carbonado, the so-called “black diamond”, a very rare variety of diamond used in industry.

The Chapada concentrated practically all the world’s production of carbonado, and it was in the vicinity of Lençóis that a stone of no less than 3,167 carats was found, named “Sérgio” – to this day the largest diamond ever seen on the planet.

In the 20th century, the arrival of the synthetic diamond led to the extinction of carbonate mining.

But not the gold and diamond, which continue to spring from the Chapada’s ground, albeit in an artisanal way, since Ibama banned the use of dredges for mining in 1998.

The gold still shows up in Rio de Contas, and the diamond usually appears near Mucugê and Igatu.

Aguinaldo Leite dos Santos, or Guina, spends three days a week mining in Igatu. “I have already picked up 140 stones in a week,” he says.

He keeps them in his wallet and goes out to sell them in Andaraí, where diamond mining brings in around 300,000 reais a month. “You can still make a living from diamonds around here.

We make an agreement with a boss, who gives us food in exchange for half the profit. So there are almost no expenses. It’s getting stuck that’s difficult.”

Video of the History of Garimpo in Chapada Diamantina

Igatu na Chapada Diamantina

História do Garimpo da Chapada Diamantina

Pedras Preciosas na Chapada Diamantina20:23

Garimpo na Chapada Diamantina04:00

Diamante brought mining in the 19th century in Chapada Diamantina

Long before they took over the windows of fancy jewelry stores like H. Stern, diamonds abounded in the Chapada Diamantina in the mid-19th century. In 1844, they were abundant, more precisely in the hands of José Pereira do Prado, Cazuzinha do Prado, in the municipality of Mucugê.

Having found two stones, one and four carats, Cazuzinha returned to the site, according to the book “Chapada Diamantina – Águas do Sertão”, with “14 men of his confidence and a load of beaters, carumbés, frincheiros, marrões, sieves and hoes”. The balance of the venture? Six arrobas, or about 90 kilos, “of thick diamonds”.

Map of the Trails and Tourist Spots of Chapada Diamantina

But of course such a lustrous find would not remain silent. One of the 14 men decided to sell his share elsewhere.

Caught, he was accused of stealing the diamonds in Minas Gerais, arrested and forced to confess where he had mined them.

Soon a new mining cycle was underway – for the region, it was even more opulent than the gold one in the 17th century.

Mucugê, Andaraí, Palmeiras and Lençóis were the most crowded cities. At the height of the gold digging, Lençóis, notorious for the quality, quantity and size of this stuffing, became the third most important city in Bahia, behind Salvador and Feira de Santana.

In the 1850s, it had about 25,000 inhabitants, two and a half times what it has today, when the city lives on tourism and receives an average of 100,000 tourists a year.

In 1867, huge deposits were found in South Africa. The price of diamonds fell, and Brazil’s hegemony in this market was compromised.

It did not take long, however, for the Chapada to become attached to carbonate, a heat-resistant mineral valued by the European and North American industry of the time.

In keeping with local (and national) tradition, the profits from this extraction did not turn into permanent benefits either, and in the early 20th century, carbonate production fell, leading many workers to emigrate.

A last significant mining breath came in the 1980s: with mechanized mines, diamonds that had previously been inaccessible were mined.

But moving the heavy machines that did this work was not easy. What’s more, the idea of environmental protection had gained momentum. Mechanized mining was banned by the federal government and the state of Bahia in 1996.

Today, there are sparse attempts to exploit something. It is not uncommon to find residents with generous land – according to Ibama, only 12% of the diamonds in the Chapada Diamantina have been exploited. But these are residents who say they are resigned to the law: they swear they will leave the potential in their backyard unfulfilled.

From Mining to Tourism in Chapada Diamantina

Lençóis is not only known for being the main access to the Chapada Diamantina. Formerly called the Diamond Capital, Lençóis has a lot of history and a past marked by riches and traditions.

According to historians, Lençóis Bahia was discovered in the 19th century due to the exploration of diamonds in the region of Mucugê. The name of the city originated from the lagedos through which the river passes, down the mountain. The image is similar to an embroidered sheet.

For a century gold was the main wealth of the region and in this period the Royal Road was built to facilitate transportation throughout the region from North to South.

From the reduction of gold begins the exploitation of diamonds and the emergence of mines in Lençóis.

The exploitation of diamonds came to an end around 1870 when the so-called “Era dos Coronéis” began. The main character of the Lençóis region in this period was Colonel Horácio de Mattos.

In the middle of the 20th century Lençóis went through a strong economic crisis due to the great demand for diamonds, which led to the exhaustion of the exploitation of the stone. The activities in the mines ended in 1994 and from that another form of wealth was discovered in the region of Chapada Diamantina: Tourism.

The Chapada Diamantina National Park was created and in 1973 the city of Lençóis was listed by IPHAN (National Artistic Heritage Institute) as a National Heritage Site. Since then, tourism is the main form of income in the Chapada Diamantina region.

History of Mining in Chapada Diamantina

Tourism and Travel Guide to Chapada Diamantina and Bahi