Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

The history of the northeast begins with the discovery of Brazil and the northeast owes its birth and development around the sugar society

Ground zero of Brazilian history was in the northeast, the history of the northeast owes its birth and development to the sugar mill.

Today, while carrying nurcas of the colonial past, the region discovers new paths to modernization.

What all Brazilians identify as the Northeast region is a relatively recent notion: until the beginning of the Republic, this “upper” part of the country was called, without distinction, the North.

The regional cut was born with the efforts to industrialize the territory; during the last century, the region was divided in different ways and received different names.

The Northeast of today, composed of nine states, results from the division established by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in 1970.

In this process, distinct histories, cultures and trajectories were bundled under the general name of Northeast. Thus, there are many ways to retrace the region’s path.

The most conventional is to establish as a starting point the moment when the Portuguese squadron commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral landed on the coast of present-day Porto Seguro, in Bahia: it was in the Northeast that the initial encounter – between the Old and the New World – took place, which would give rise to what would one day become the Brazilian nation.

Watch the videos on the “History of Brazil”

Guerra dos Canudos

Recife dos Holandeses

A viagem de Predro Alvares Cabral04:40

Ciclo da cana-de-açúcar

Descobrimento do Brasil em 22 de abril de 1500

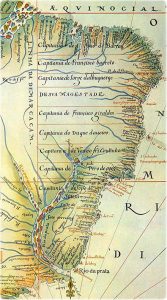

Capitanias Hereditárias08:24

Descobrimento do Brasil - Aula09:54

Parque Nacional Histórico Monte Pascoal02:16

To the disappointment of the conquistadors, the lands were lush, but poor in the spices and noble metals that drove the navigations.

The wealth here was something else: brazilwood, used in Europe as a dye for fabrics.

The Portuguese only began settling the colony thirty years after first landing, although they frequently visited the northeastern coast in search of timber, which also attracted smugglers, pirates and adventurers from other countries.

In 1534, the Portuguese occupation effectively began, with the division of the colony into large plots of land, the hereditary captaincies.

The system of captaincies failed – only São Vicente, in São Paulo, and Pernambuco, also called Nova Lusitânia, prospered, where sugar cane agriculture quickly took hold.

In 1548, the government-general was established; the following year, Tomé de Sousa, the first governor, landed in the village of Pereira – a settlement in the bay of Todos os Santos, where the port of Barra is located today – to found the administrative center of the colony. Salvador was born.

The Tupinambás Indians, the former inhabitants of the Recôncavo, were seized for farm work and converted to Catholicism; many fled to the interior of the continent.

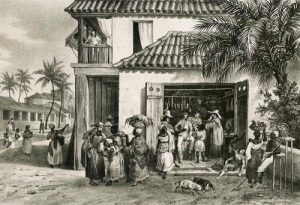

Gradually, the colonial enterprise was established, with the organization of the export of brazilwood and the construction of the first mills.

CRONOLOGY OF THE HISTORY OF THE NORTHEAST

THE SUGAR SOCIETY IN THE NORTHEAST

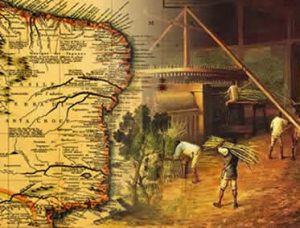

It is difficult to pinpoint the precise moment when the sugar cane was introduced in Brazil; in the second half of the 16th century the sugar industry was already established in the Northeast – and it would sustain the colony’s economy over the following centuries.

The sugarcane plantations spread along the northeastern coast, and Pernambuco and Bahia emerged as the most important producers; the fertility of their lands was combined with the relative proximity to Europe and the presence of good ports (Recife and Salvador).

Sugar production became the most dynamic of the entire colony; it was based on large property, monoculture and slave labor – indigenous initially and then African: Salvador became the main importing center for slaves from Guinea, the Costa da Mina and the Gulf of Benin, a position from which it only declined from the 18th century onwards, when sugar began to lose space to gold from Minas Gerais and the center of the slave trade moved to Rio de Janeiro.

Not by chance, the Northeast is the region that concentrates the largest number of blacks and the one that most effectively preserves cultural traditions of African origin.

The core of sugar society was the engenho (sugar mill), composed of mills and furnaces that stood amidst the immense cane fields.

The masters and their families lived in the so-called casa-grande; the slaves lived in the senzalas. This opposition – or complementarity – between master and slave would mark the whole of colonial society.

EUROPEAN INVASIONS IN THE NORTHEAST

Throughout the 16th century, many villages were founded by Portuguese grantees and explorers in the coastal lands north of Bahia.

In some regions, the Portuguese occupation was only consolidated in the following century, hampered both by the resistance of the indigenous peoples and by the invasions of other Europeans.

The French explored lands now belonging to Sergipe, Paraíba, Alagoas and Rio Grande do Norte from the first years after Cabral’s expedition.

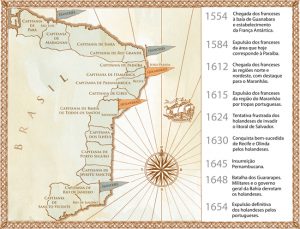

In 1612, they invaded Maranhão and founded São Luís; they were defeated in 1615.

Six years later, the Portuguese government encouraged the arrival of Azorean settlers to populate the region and created the state of Maranhão, which included the so-called Grão-Pará and reported directly to Lisbon. Maranhão and Pará separated in 1774.

Attracted by sugar, the Dutch also invaded Portuguese territory, with the support of a company, the West India Company.

In 1624, they attacked Salvador, but were quickly defeated; in 1630, they returned to charge Pernambuco. After conquering Recife, the Dutch invaded Filipéia, now João Pessoa (1637), Fortaleza (1640) and São Luís (1641-44).

THE DUTCH BRAZIL – HISTORY OF THE NORTHEAST

The seven years that followed the invasion of Pernambuco by the Dutch were marked by wars of resistance; in 1637, with the Portuguese capitulation, Count Maurício de Nassau, governor of the Dutch possession, landed in Recife.

The period during which Pernambuco remained under Dutch occupation has passed into the popular imagination as a kind of golden age, a fabulous and almost noumenal time.

Nassau established a policy of religious tolerance – two synagogues functioned in Recife – and conciliation with the Portuguese who lived there; he promoted the arrival of scientists who bequeathed important studies on topography and tropical diseases, and artists such as Frans Post, Albert Eckhout and Zacharias Wagener, who recorded American nature and scenes of colonial life.

The fall in the international price of sugar and disagreements with the West India Company forced Nassau to return to Europe in 1644, and the following year the Dutch were definitively expelled from the Portuguese colony – taking cane seedlings, which they planted in their colonies in the West Indies. Portugal retook Pernambuco, but lost its monopoly on sugar production forever.

Beyond Sugar – HISTORY OF THE NORTHEAST

The sugar company was the economic axis of the Northeast during the first centuries of colonial Brazil. However, other products grown in the region played important roles in colonial society.

Tobacco, whose cultivation was predominant in the Recôncavo Baiano, was widely used as a currency on the coast of Africa by slave traders; the finest varieties were exported to Europe.

Livestock farming emerged in the shadow of the mills, but eventually entered the territory.

Cattle breeding drove the occupation of the vast and flat northeastern hinterland – including Piauí, the only state whose settlement occurred from the interior to the coast, by cowboys from Bahia – and resulted in what many call the “leather society”.

Cotton production, present since the beginning of colonization, took off at the end of the 18th century, when sugar exports began to decline and the English Industrial Revolution took place; when the War of Secession interrupted North American production, Brazilian production was boosted, particularly in Maranhão.

TEMPS OF WAR

-<nbsp;-<nbsp;HISTORY OF THE NORTHEAST

In the 18th century, sugar profits fell, depressed by competition from Antillean production.

The discovery of gold in Minas Gerais gradually shifted the economic axis to the Southeast. Several revolts reflected the unstable situation of the Northeast.

In 1684, in Maranhão, the Beckman Revolt was one of the first protests of the colonists who disagreed with the Crown’s policy, especially regarding the obstacles to indigenous slavery and the form of trade imposed by the Companhia de Comércio do Maranhão, which monopolized trade in the region.

Between 1710 and 1712, the sugar crisis resulted in the so-called Mascates’ War, a conflict between the indebted rural aristocracy, represented by the landlords of Olinda, and the merchants – mascates – of Recife, mostly of Portuguese origin.

In the second half of the 18th century, the liberal and republican ideals that would result in American independence and the French Revolution began to circulate in the colony.

In 1798, the Conjuration of the Tailors broke out in Bahia, a movement that included the participation of popular sectors: for the first time, social demands were added to the desire for independence.

In 1817, the Pernambuco Revolution spread from Recife to Rio Grande do Norte, entering the hinterlands and bringing together groups of different interests, such as landowners, merchants, military personnel, judges and priests under the banner of the republic and the independence of the Northeast.

Social revolts followed the proclamation of independence. Independence itself, moreover, was not peaceful in Bahia, where it was only consolidated in 1823, with the defeat of the Portuguese troops that still resisted in the Recôncavo.

Even today, the highlight of the state’s civic calendar is Dois de Julho, the day of victory, and not the Sete de Setembro celebrated in the rest of the country. In 1824, Dom Pedro I dissolved the Constituent Assembly and decreed the first Brazilian Constitution, measures that rekindled in Pernambuco the republican fervor of 1817.

The province joined Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte and Ceará in the so-called Equator Confederation, which was defeated after four months of fighting.

Throughout the 19th century, other movements broke out across the country, reflecting Brazil’s political instability and the dissatisfactions of various segments of society.

In the Northeast, the Cabanas War in Pernambuco (1832-35) brought together small landowners, Indians and slaves in a religious movement calling for the return of the emperor (Dom Pedro I had returned to Portugal in 1830, abdicating the throne in favor of his five-year-old son; several regents were at the head of the country until 1840, when Pedro II came of age).

In Salvador, middle-class merchants and officials came together in the republican Sabinada movement (1837-38), violently repressed.

In Maranhão, the Balaiada (1838-41) brought together small landowners and mestizos; the Praieira Revolution in Pernambuco (1848) opposed the two parties that would dominate imperial politics – the Liberal (composed mainly of the urban middle class) and the Conservative (formed mainly by large landowners).

It is also important to remember the slave rebellions that agitated the Recôncavo Baiano during that century. The largest of these was the Revolt of the Malês (Muslims), which took place in Salvador in 1835 and foreshadowed the unsustainable situation towards which the slave order was heading.

The abolitionist movement spread throughout the Northeast; among its most notable names are the Bahians Rui Barbosa, Luís Gama and Castro Alves, the Pernambuco Joaquim Nabuco, the Potiguar Aimino Manso and Francisco do Nascimento, from Ceará – a state that abolished slavery in 1884, four years before the promulgation of the Golden Law.

CORONELISM AND CANGAÇO

In the First Republic, the country crystallized coronelismo, a political practice based on the power of large landowners – the colonels, a name inherited from the National Guard, a civilian militia created during the Empire to ensure internal order.

Supported by their bodyguards, the jagunços, the colonels in the interior of the Northeast imposed their will by force; in a complex network of favors and commitments, they exchanged protection, public offices, schools, medicines for votes for representatives of their interest.

Frequent rivalries between families were resolved with violence. A feud with colonels resulted in the assassination of the governor of Paraíba, João Pessoa, a fact that would become the trigger for the 1930 Revolution, which would bring Getúlio Vargas to power.

If the jagunços acted at the service of the colonels, the cangaceiros were independent bandits who, for decades – from the early years of the 20th century to the 1940s – spread terror through the northeastern hinterlands, invading and looting houses and cities.

Their nomadic life and defiance of authority, however, would lend them a romantic aura. Lampião, the most famous of them, is still seen as a myth today. After years of spectacular escapes, he, his companion and his men were ambushed and killed in 1938 in Angicos, Sergipe, by government troops.

Corisco, his successor and the last of the cangaceiros, was captured and killed two years later.

THE WAR OF CANUDOS – A HISTORY OF THE NORTHEAST

“There were only four of them: an old man, two grown men and a child, in front of whom five thousand soldiers roared angrily.” Thus Euclides da Cunha described, in Os sertões, the outcome of the Canudos War.

The conflict – a consequence of what at first appeared to be a modest religious movement among farmers and small landowners in the interior of Bahia – took place between 1896 and 1897 and shook the newly born Brazilian Republic.

Coming from Ceará, the blessed Antônio Mendes Maciel, known as Antônio Conselheiro, wandered for years through the sertão in religious preaching, amassing followers.

In 1893, he settled on the banks of the Vaza-Barris river, where the so-called Canudos settlement was formed, whose population grew rapidly. Rumors that Conselheiro’s faithful would invade Juazeiro to collect a debt led to the first attack by government troops on the village – which, surprisingly, was victorious.

Two federal government expeditions, although heavily armed, also failed.

The incredible resistance of Canudos, considered a stronghold of monarchists and fanatics, humiliated the Brazilian Army and became a national issue.

Finally, in August 1897, after more than three months of fighting, a troop of 8,000 men destroyed the village. Residents captured alive, like those who surrendered, were executed.

NEW WAYS – HISTORY OF THE NORTHEAST

The sugar mill was the blessing and the curse of the Northeast: on the one hand, it guaranteed its economic consolidation and presided over the genesis of its rich culture; on the other hand, its land structure determined the serious social distortions that lasted throughout its history.

Marked by misery and very harsh natural conditions – large areas regularly plagued by long periods of drought – the region experienced a continuous flow of migrants throughout the last century.

The exploitation of rubber in the Amazon attracted many northeasterners, especially during the great droughts of 1877 and 1915; in the following decades, they moved to the centers of the Southeast, looking for jobs in industry, and to the Midwest, due to the construction of Brasilia.

The movement still continues. The Northeast, which was the country’s most populous region in the 1870s, is now home to about 30% of Brazil’s population.

In 1959, the Brazilian government created a regional economic planning body, the Superintendency for the Development of the Northeast (Sudene), as part of an effort to reorganize the social order and modernize labour relations in the countryside.

At that time, the region did not yet include the states of Bahia and Sergipe.

Today, despite the marked internal imbalances, the Northeast has important industrial centers, such as the petrochemical complex of Camaçari in Bahia, the textile complex of Fortaleza in Ceará, and the iron industry of Carajás, which occupies a large part of Maranhão.

In the São Francisco valley, Petrolina has established a successful irrigated fruit plantation. The population is no longer massively rural, and the cities, especially the coastal capitals, are becoming metropolises.

Northeastern culture – manifested in literature, music, the arts and cinema – continues to exert an immense influence on the country. Oscillating between poverty and exuberance, the archaic and the modern, the Northeast region faces its challenges and writes its history.

History of the Northeast

Tourism and Travel Guide to Bahia, Salvador and the Northeast