Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

The Nossa Senhora of Monte Serrat, originally called the Castle of Saint Philip, is considered to be an extraordinarily important example of our early fortified architecture, as it is the most archaic model of local defences that has survived without major transformations.

In this respect, it is perhaps the oldest existing in the whole of Brazil.

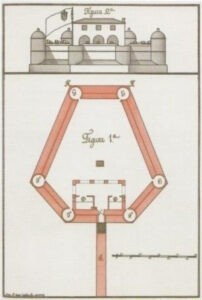

In fact, in Albernaz’s cartography from the first quarter of the 17th century, which also includes the Fort of Saint Albert, the old Tower of Saint Anthony of Barra and the Tower of Saint James of Água de Meninos, the Fort of Serrat is the fourth fort represented in plan.

In this representation, it looks the same as it does today, despite the renovations by the Count of Castelo Melhor (1650-1654), Viceroy André de Melo e Castro (1735-1749), the Count of Galveias, completed on 18 October 174225, and the restoration by Góis Calmon in 1927.

The Albernaz plan is the oldest iconographic document concerning the fort completed on 18 October 1742, and the restoration by Góis Calmon in 1927.

Albernaz’s plan is the oldest iconographic document concerning the fort.

In fact, from the point of view of the city’s image, the Fort of Nossa Senhora of Monte Serrat is a reference like many other forts, but quite special because of its privileged position and extreme harmony with the morphology of the terrain.

Its round bastions were very much in keeping with the Italian fortified architecture of the transition, albeit on an infinitely more modest scale.

História do Forte de Nossa Senhora de Monserrate

For the less informed reader, it should be emphasised that the fort’s name is not related to the Baluarte de Monserrate.

This was part of the approximate defensive perimeter of Salvador, probably located on the hillside below the Fortress of Santo Antônio Além-do-Carmo, as described by Captain João Coutinho.

Assuming that it was built during the time of King Francisco de Sousa, as Teodoro Sampaio and many other illustrious researchers of our history believed, one imagines that its design may well be the work of Baccio de Filicaia, who was in the service of that governor.

In his work on the military history of Brazil, written in the 18th century, Colonel José Mirales believes that it dates from the time of Governor-General Manoel Teles Barreto (1583-1587).

What is certain is that it was already part of the fortresses mentioned by Diogo de Campos Moreno in his report of 1609.

Even if it had the capacity to receive a greater number of pieces, Monserrate had no more than six or seven, since “a pygmy should not be given the same weapons as a giant […]”, as was the opinion of Master-decamp Miguel Pereira da Costa, an expert on the subject.

In fact, Caldas, who saw it as an “old and defective fortification”, found it in the mid-18th century with nine pieces, which he considered more than enough for its firepower.

He also found it with the two front turrets cut down to the height of the barbette to increase the line of fire. These turrets, at some point in the past, were rebuilt.

Their “sentry boxes”, as the common people usually consider them, are actually tiny turrets whose function was to flank the curtains with musket fire (a type of portable firearm).

Because it had a parapet to the barbette, this fortress was always frowned upon by the gunners, as they were more exposed to enemy fire.

All these devices, however, were intended to increase the fire capacity of the fort, making it receive more pieces and unobstructing the visibility of the frontal shot.

It had, among other things, a defect peculiar to many fortifications in Salvador, which was the existence of a stepfather, formed by the hill where the headquarters of the Coordination of Environmental Resources is currently located, at a higher altitude than the Monserrate stronghold.

Unlike other defences of our city, which have never fought against an external enemy, the former Fort or Castle of São Felipe, today the Fort of Nossa Senhora de Monserrate, has been involved in some struggles throughout its four hundred years of existence.

The behaviour of its defenders is, however, a matter of controversy.

During the first Dutch invasion, it was taken by the Batavos, after having exchanged fire with some ships of the enemy squadron.

Its resistance to the assault seems not to have been tenacious because, once the city was occupied, there was no alternative but to retreat.

Moreover, it was not difficult to land on the beaches of the Itapagipe peninsula and cut off communication with the city garrison.

There is a new disagreement among historians about what happened at Monserrate Fort with the arrival of Fradique de Tolledo in 1625.

Some believe that, at the sight of the powerful fleet, the Dutch retreated to the city and abandoned it, a prudent and salutary measure.

Aldenburgk says that his garrison even fired on the ships of the Portuguese-Spanish squadron, then withdrew the following night.

Those who wanted to valorise the Portuguese achievements, such as the military man Francisco de Brito Freire, author of História da Guerra Brasílica, speak of the fort being taken by surprise. Where bravado abounds, historical truth is lacking.

Thirteen years had elapsed since the Portuguese reoccupation of the fort when, “on the afternoon of 21 April, Major van den Brand advanced with some people along the beach, leading five pieces, and took it from Captain Pedro Aires de Aguirre, who had few soldiers and six cannons”.

It was the invasion of Nassau of 1638. The Dutch only vacated it when they returned to Pernambuco.

In particular, it should be said that Aguirre had been a corporal at the fort since 1618 and was certainly an old man.

The Fort of Nossa Senhora of Monte Serrat would hibernate for some two hundred years, waking up sporadically from its nap with some commemorative salute when it was occupied by the Sabinada insurgents in 1837.

It was “his third warrior adventure”.

The seditionists, who took it with the help of the Brasília liner, exchanged fire with ships of the Imperial Navy, but surrendered in the face of the more modern artillery of the Regeneração corvette and the brig Três de Maio, which landed the garrisons supported by a legalist detachment that advanced by land.

During the Second Reign, the Christie question, which involved incidents with ships and resulted in a diplomatic break with England, raised the issue of remodelling the fort. This was carried out in 1863, in accordance with the recommendations of Colonel Beaurepaire Rohan of French origin, who was then collaborating with the country’s security.

Map of Tourist Attractions of Salvador da Bahia.

From then on, there is no knowledge of any substantial intervention for its conservation until, in a deplorable state, it was the object of restoration work during the government of Góis Calmon (1924 to 1928), as part of the project to “beautify” the areas of Montserrat.

At that time, a commission was set up which included Captain Cunha Menezes, Professor Alberto de Assis and the engineer Américo Furtado de Simas.

The most recent restorations, undertaken by the Brazilian Army, were minor and did not alter the appearance of the defence.

The Fort of Nossa Senhora de Monte Serrat is located at Ponta de Humait in Salvador da Bahia.

History of the Fort of Nossa Senhora de Monte Serrat – Tourism and Travel Guide of Salvador da Bahia