Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

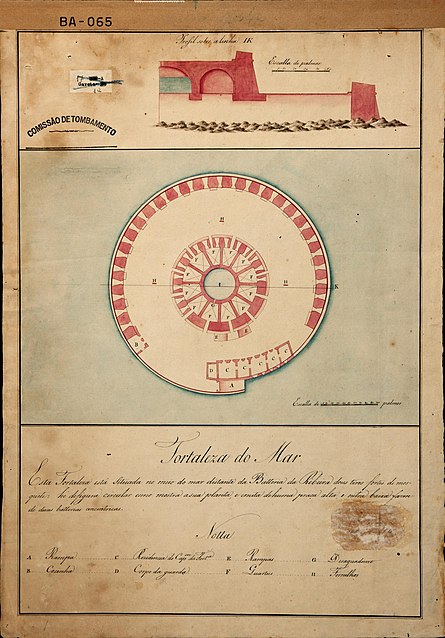

The fort of St Marcellus or Forte de São Marcelo in Salvador was built on a crown of sand, and because it is the only one with a circular plan;

The history of the Forte de São Marcelo is full of curious episodes to say the least. In 1624, for example, about a year after it was built with the aim of protecting Salvador from invasions, the fort was taken over by the Dutch who, from there, made violent attacks on the city.

But about 15 years later, it was thanks to this fort that the Dutch were kept at bay in their second invasion attempt.

Some chroniclers of the past confused the old Fort of the Sea, which was that of Laje, closer to the mainland, with the current Fort of Nossa Senhora do Pópulo and São Marcelo, called only Fort of São Marcelo or, popularly, Fort of the Sea.

Many modern historians have been drawn into this misunderstanding.

História do Forte de São Marcelo ou Forte do Mar

What the documents show, and Luiz Monteiro da Costa partly proved, is that there were two Forts of the Sea:

- The first of them, from the early 17th century, closer to the Ribeira de então, was built as a quadrilateral stronghold on a rocky outcrop, the famous “lagem”.

- The second, corresponding to our São Marcelo, was built, with a circular partition, on a crown of sand.

The documents that Monteiro da Costa uses in his argument make it clear that the fortification referred to as Forte da Laje or Forte do Mar, in the first half of the 17th century, was close to the beach and could not correspond to the current Forte de São Marcelo.

It is worth noting that, in his description of the fighting between the Dutch and the Portuguese that took place there in 1624, Aldenburgk reported that when the latter took the then “Forte do Mar”, which was still unfinished and protected by cestons, they jammed the battery’s cannons and retreated because of the ground fire.

According to a highly credible expert, Marshal Sebastien Vauban, the maximum useful range of a musket at the time was 120 to 125 toesas (237.6 to 247.5 metres).

According to the current aerial photogrammetric survey of the city, our Fort of St Marcellus is some 600 metres from the lower part of the Lacerda Elevator, which would rule it out as the successor to the old Fort of Lajem.

The iconography is also very clear. The oldest image, which shows the first Forte do Mar in its square redoubt version, in the Livro que dá razão do Estado do Brasil, shows a jetty connecting the fort to the land.

The size of this jetty, even considering any flaw in the artist’s scale, could not be a link from our present-day São Marcelo to the land.

Peter Netscher, a 19th-century Dutch military officer and historian, also quoted by Monteiro da Costa, in his account of the epic invasion says, referring to the storming of Fort do Mar: “Piet Heyn himself, followed by his ship’s bugler, was the first to climb the enemy fortification, forcing the entire garrison to escape, either by ford or by swimming”.

It is true that a good swimmer could cover the five hundred metres between the present-day São Marcelo and the beach at the time, but it would be totally improbable to ford it, no matter how much the bathymetry of our port had changed.

From this point of view, regarding the shallow depth between the fort and the land, the following information appears in Aldenburgk’s caption for the illustration of the text on the capture of Salvador, translated by Silva Nigra: “A battery built of hard stone, far from the land, which at high tide can be passed behind with a boat”.

The statement is obvious and deserves no further comment.

There is also a document dated 1668, signed by Francisco Barreto, Governor-General from 1657 to 1663, which is an opinion on the defence situation of Bahia and its Recôncavo, made at the request of the Overseas Council.

In one passage, he clearly states: “I built Fort São Marcelo in the middle of Bahia, so that with Fort Real (Fort São Felipe e Santiago, successor to Fort da Laje) and Fort São Francisco, the anchorage for ships could be defended”.

More recently, when IPHAN carried out restoration and consolidation works at the Fortress of Nossa Senhora do Pópulo and São Marcelo, five internal surveys were ordered in order to find out the substrate supporting the foundations.

The reports of the Concreta company show, when examining the drilling profiles, that the building is on an artificial rockfill, with rocks of various origins, some of them limestone.

After this stratum there is a drop in resistance, because there is no “lagem”. It is a crown of sand, as has been described before, and so the defence erected there could not be the Fort da Laje, as some historians have claimed.

The first fort, called “do Mar”, was built on a rocky outcrop known to the ancients as a “lagem”, and was in the shape of an unbulwarked quadrilateral, which in the technical language of the treatise writers was called a redoubt.

The report that formed the basis for the Livro que dá razão do Estado do Brasil, produced in 1612 by Diogo Moreno, already shows a map of the City of Salvador with the fortification “da laje” connected to the beach by a jetty.

In the copy of the valuable manuscript in the Oporto Library, an interesting feature is that the Fort of the Slab has been added on a paper pasted over the original drawing, as if it were an update.

In addition to the fleeting nature of the fortification, the iconography shows that it had no offensive capacity in the frontal direction, since the trestles were depicted on the sides, and the pier continued in the west direction, a side not equipped with artillery.

From the date of these records, we can imagine that the Laje Fort was built between 1609 and 1612, i.e. during the government of Diogo de Menezes.

As the defence of Cabeça do Brasil, both on land and at sea, remained precarious, and certainly due to the admonition of Captain Francisco Frias da Mesquita, the chief engineer, it was decided to improve the protection of the port under Mendonça Furtado (1621-1624), but as always too late.

Authorisation came by means of the Royal Charter of 3 August 1622, which, in a certain passage, reads as follows: “[…] and making a new fort and jetty on the slope in front of the city to shelter ships […]”.

Again by the hand of Frias da Mesquita, the redoubt on the slab was given a new project to leave the condition of a “temporary fortification” and become a “permanent” one, even without any great defensive pretensions.

Based on Portuguese iconography from after the retaking of Salvador from the Batavos, such as the well-known Plan of the Restitution of Bahia of 1626, we find a new fort in a quadrilateral shape, but with a kind of counterguard on the front face.

This detail gave it a similar shape in this direction to the Fort of the Magi in Natal, also attributed to Frias da Mesquita.

At the rear, the Potiguar fort has a hornaveque-like protection, a defensive element that does not seem to exist in our Fort da Laje.

In fact, the proximity of Ribeira to the rear of the “laje” fortification makes such a defence perfectly dispensable.

The same configuration can be seen in the engraving by the Portuguese cartographer Benedictus Mealius Lusitanus depicting the retaking of Salvador, produced to illustrate Father Bartolomeu Guerreiro’s 1625 account, Jornada dos vassalos da Coroa de Portugal.

The Dutch engraving of 1638 showing the City of Salvador at the time of the failed attack of Nassau, already commented on, points to an identical solution for the former propugnacle of the sea.

The important cadastral survey of Salvador from 1779, which is in the Military Archives of Rio de Janeiro, also shows the same configuration.

There are strong indications that this plan was drawn up by Sergeant Major José Antônio Caldas.

As for the current Fort of the Sea or of Our Lady of Pópulo and Saint Marcellus, it was born with a circular plan and, even with some modifications during its history, still shows the same configuration.

This type of fortress design is not very common, but it is not unusual.

Luiz Monteiro da Costa attributes the plans for the Fort of São Marcelo to the French military engineer Pedro Garcim (or Garim), who lived in Salvador for some time in the 17th century.

Carlos Ott, another scholar of the city’s history, is less emphatic, preferring to attribute to this engineer only the initial execution of the construction, which is considered more judicious.

In reality, the fact that an engineer started the work does not necessarily mean that he was the author of the project.

In the case of the Fort of St Marcellus, it is more likely that the “moths” came from the Kingdom. This hypothesis is based on the fact that a circular fort with a higher central turret, constituting a tall battery, had already been built in Lisbon since the end of the 16th century.

This was the Fort of Saint Lawrence of the “Cabeça Seca”, which, like Saint Marcellus, used the support of a crown on the Tagus bar.

This work, using the same technique of rockfill to reinforce the base, was begun by the engineer Father João Vicente Casale, who moved from Naples to Spain in 1588 and then to Lisbon with his nephew Alexandre Massai, alias Alexandre Italiano, also a military engineer.

The next person to take charge of the Fort of São Lourenço, now better known as the Bugio Fort, was Leonardo Turriano, who left the construction at the height of the foundation.

The information, from 1646, comes from his son, Friar João Turriano, who, like his father, was Engineer of the Kingdom by appointment of King João IV.

Examination of Turriano’s drawings indicates that, if Garcim is the author of the project for the Fort of Saint Marcellus, which does not seem credible, he was faithfully inspired by a prototype that already existed in Portugal, especially in its initial version, with a turret and high square.

It is also worth drawing attention to the date of João Turriano’s drawings for Bugio, 1646, which was before the Royal Charter of 1650 authorising Count Castelo Melhor to build the current Fort of the Sea.

We would emphasise, however, that our Forte do Mar is not a perfect circle (although some registers represent it as such), due to construction problems, but this does not change its affiliation.

The work on the Fort of Nossa Senhora do Pópulo and São Marcelo was far from being carried out quickly. The rock-fill work to stabilise its foundations took a long time.

Eighteenth-century engineers were still trying to improve its defensive condition and eliminate imperfections.

Reading some Royal Charters from after 1650 clarifies the origin of the lithic material used in the rockfill: some came from the Recôncavo (granite rocks), some from the neighbouring region (calcareous sandstones), possibly from the Preguiça or Itapagipe area, and some from Portugal (limestone) as ship ballast.

This information is suggested by the documentation and by the sampling that was done in the survey.

It can be assumed that the Fort of Saint Marcellus was originally a simple tower, since construction began, as would be logical, with the central turret. This is suggested by an engraving in the National Library of Lisbon, also reproduced in the Essay on the iconography of Portuguese cities overseas, which shows a tower surrounded by rockfill in the harbour of Salvador.

Another sign is the meagre nine-piece artillery available in the seventies of the 17th century.

Twenty years had elapsed since the construction of the Fort of the Sea was authorised and work was still in progress when Governor-General Afonso Furtado de Mendonça (1671-1675) requested a technical report on the state of the defences of Salvador and the Recôncavo.

With regard to this defensive work, the document states: “The Sea Fortress N. Senhora do Pópulo, is made of stonework, is still to be finished, and in the form of the order of H.A. we are beginning to deal with its work, it is of great consideration for the safety of the ships and the Enemy Armadas cannot easily reach the City […]”.

We entered the 18th century and our fort still needed some adjustments. At that time, it still had a taller central turret with gunboats, and a lower outer ring, also with gunboats, with a greater density of artillery.

Master of the Field Miguel Pereira da Costa protested against this solution, which made it very similar to the Bugio Fort on the Tagus, in a report dated 1710: “In the beach of this city is the Sea Fort, more than a musket shot from land, in a circular shape; with a high square, but this one, besides having little capacity, bothers the lower one”.

Miguel Pereira’s judicious advice would only be heeded many, many years later.

In 1758, when Captain José Antônio Caldas, an accomplished draughtsman, illustrated the text of his book with registers of fortresses, the Fort of São Marcelo still had a turret and gunboats.

These elements persisted into the late 18th or early 19th century, as can be seen not only in the profile of the city drawn up by Captain José Francisco de Souza in 1782, but also in that of Vilhena in 1801.

Brigadier José Gonçalves Galeão, coordinator of a report on the fortifications of Salvador dated 1810, criticises the high turret, troneiras and casemates, suggesting that it was only after that date that the transformations that led to the disappearance of the high square and the replacement of the troneiras with a parapet on the barbette took place.

The Galeão team responsible for the report included a Lieutenant Engineer called João Teixeira Leal, who left a collection of very good drawings of our fortresses, with numerous reproductions and copies in both Portuguese and Brazilian archives. Apparently, the report in question was illustrated by Leal.

One of these illustrations, which he signed in his capacity as Captain – thus after 1810 – shows the Fort of São Marcelo more or less as we know it today.

One of the moments of great movement in the quest to defend Salvador and other Brazilian cities occurred after the second French invasion of Rio de Janeiro in 1711.

Brigadier João Massé, who was in Brazil at the time, reported that the Fort of São Marcelo was not yet finished, and that he had drawn up specifications for it in order to instruct the opening of tenders for its construction.

Massé’s specifications provided for rockfill 20 palms (4.4 metres) larger than the diameter of the plan submitted, with foundations rising up to 2 palms (0.44 metres) above the low water mark and allowing a 3-palm (0.66 metre) footing to rise with the wall, with a drag of 1 palm over 5 (20%).

The later report on the fortifications of Salvador, signed by Massé, Master of the Field Miguel Pereira da Costa and Captain Gaspar de Abreu, repeats, as regards the fortification in question, the words of Miguel Pereira in his report of 17 June 1710.

Today, our old propugnacle, one of the most significant examples of the fortifications of colonial Brazil, survives with great difficulty, despite some improvements it has received.

It urgently needs its foundations and protective rockfill to continue to bear witness to our memory. If it does not receive this minimum of care, its outer ring will collapse and, subsequently, the rest.

Even though it did not take part in any military action in defence of our port, it is one of Salvador’s most expressive postcards, a living testimony to our history.

History of the Forte de São Marcelo or Forte do Mar in Salvador