Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

Northeastern music includes rhythms such as coco, xaxado, martelo agalopado, samba de roda, baião, xote, forró, Axé and frevo, among other rhythms.

The armorial movement in Recife, inspired by Ariano Suassuna, did an erudite job of valuing this popular rhythmic heritage from the northeast (one of its best-known exponents is the singer Antônio Nóbrega).

Several artists have continued the legacy of Luiz Gonzaga, such as Dominguinhos, Sivuca, Jackson do Pandeiro and Waldonys.

In literature, we can mention the popular cordel literature that dates back to the colonial period (the cordel literature came with the Portuguese and has its origins in the European Middle Ages) and numerous artistic manifestations of a popular nature that are manifested orally, such as the singers of repentes and embolada.

In classical music, composers Alberto Nepomuceno and Paurillo Barroso stand out, as does Liduíno Pitombeira from Ceará today, and Eleazar de Carvalho as a conductor.

Rhythms and melodies from northeastern music have also inspired composers such as Heitor Villa-Lobos (whose Brazilian Bachiana No. 5, for example, in its second part – Dança do Martelo – alludes to the backlands of Cariri).

Northeastern popular music includes rhythms such as coco, xaxado, martelo agalopado, samba de roda, baião, xote, forró, Axé and frevo, among others.

The armorial movement in Recife, inspired by Ariano Suassuna, did an erudite job of valuing this popular rhythmic heritage from the northeast (one of its best-known exponents is the singer Antônio Nóbrega).

Genres and Rhythms of Northeastern Music

Forro Pé de Serra08:03

História do Frevo02:16

História do Axé Music

Bossa Nova - Chega de Saudade João Gilberto e Bebel Gilberto07:56

História da Tropicália / Tropicalismo

Various genres have emerged in the Northeast over the years.

Xote, xaxado and côco are part of the so-called forró

The Pernambucan Luiz Gonzaga was the forerunner of baião, a rhythm that alongside others such as xote, xaxado and côco form part of what is known as forró.

Several artists have continued the legacy of Luiz Gonzaga, such as Dominguinhos, Sivuca, Jackson do Pandeiro and Waldonys.

Frevo

Frevo, most common in the states of Pernambuco and Paraíba, is characterized by its fast pace and steps reminiscent of capoeira.

This genre has revealed great musicians such as Alceu Valença, Elba Ramalho and Geraldo Azevedo. These three, alongside Zé Ramalho, mixed frevo, forró, rock, blues and other rhythms. The quartet usually performs under the name O Grande Encontro.

Tropicalism / Tropicália

In the 1960s, tropicalism emerged in Bahia, inspired by the anthropophagic movement and which was to become a landmark in Brazil.

This group included the artists Tom Zé, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, among others.

Between 1965 and December 1968, an extensive and refreshing artistic activity developed with cultural and political dimensions of rare critical scope in Brazil. Avant-garde projects, largely associated with political and social interests, emerged in all areas of artistic production.

Two priority directions were defined: a so-called art of protest associated directly or indirectly with the need to raise awareness and mobilize the public, given the need to resist the calculations of the military regime, and an avant-garde art in which the imperative to renew forms, languages, processes and behaviours were considered a priority, both for the revitalization of the arts in the face of the new conditions brought about by modernization, and for the critical re-dimensioning of the imperative of cultural and political participation.

Among the artistic modalities that emerged at that time was music of protest and denunciation, generally translating hope for a “day to come”, a political utopia that had persisted since at least the beginning of the decade.

Music became the most suitable channel for conveying political projects, precisely because popular song had always been the artistic modality in Brazil with the greatest public penetration, in all strata of the population, even before the decisive developments of the cultural industry from the mid-1960s onwards, when the era of festivals brought the two modalities of participation, protest and innovation, to the fore, not without conflicts or intersections between them as to what was understood as legitimate Brazilian music or as to the most legitimized modes of political expression.

Tropicalism emerged from the combination of these various artistic, cultural and political factors that manifested themselves in popular music, theater, cinema, the plastic arts and literature.

The moment of maximum intensity and rupture occurred in 1967 and 1968, when there was an extraordinary creative explosion, which critically radicalized the intense renewal of artistic activity that had been developing since the mid-1950s.

In these two years, the social, political and cultural concerns and initiatives aimed at fulfilling the imperative of modernization that, since the modernist movement of 1922, had determined the effort to innovate art, culture and reflection in Brazil were pushed to their expressive limits.

The year 1967 was particularly remarkable: Tropicalism, unleashed with the songs Alegria, alegria, by Caetano Veloso, and Domingo no parque, by Gilberto Gil, presented at TV Record’s III Festival of Brazilian Popular Music; the release of the film Terra em transe, by Glauber Rocha; the editing of O rei da vela, a play by Oswald de Andrade, by the Teatro Oficina in São Paulo; the appearance of Hélio Oiticica’s environmental project Tropicália at the exhibition Nova Objetividade Brasileira at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro; and the launch of PanAmérica, a book by José Agrippino de Paula. These productions were listed under the generic name “tropicalism”.

Despite their differences, there was something in common between them: art of rupture, innovation in artistic languages and cultural strategies, which proposed changes in the political significance of actions, reproposing the meaning and forms of social participation in artistic and cultural activities.

Combining artistic experimentalism and cultural criticism, articulating avant-garde procedures and political participation, innovating the song by integrating non-musical effects and resources from contemporary and pop music, renewed composition processes in lyrics, melody, arrangements and vocalization and the elaboration of images with parodic and allegorical effects, the Tropicalist activity shifted the modes of expression of the aesthetic and social non-conformism evident in the most significant part of art in Brazil in the 1960s.

This non-conformism, which had been building up since the 1950s, was retranslated by Tropicalism, especially in the individual albums by Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil and the collective, Tropicália, Panis et circencis, released in 1968.

[…] Tropicalism appeared as a transgression not only because of its musical innovations, but also because it activated behaviors and incorporated them into the very structure of the song, composing a poetics of spectacularity.

The emergence of Tropicalism in 1967 not only brought about changes in the situation of popular music in Brazil, calling into question the limits of the effectiveness of the protest song, but also marked the more incisive absorption of the contributions of rock music, which until then had been only superficially experimented with by the Jovem Guarda of Roberto Carlos and Erasmo Carlos, as well as specific references to the tradition of popular music and other popular expressions.

The complexity of Tropicalism arises from its intervention in the ways of making songs in Brazil, highlighting the turn of bossa nova and explaining the possibilities of its critical function.

The very materiality of the song is modified with the introduction of avant-garde procedures (musical, theatrical, cinematographic, poetic), rock harmonies and rhythms, electronic instruments, elaborate staging, etc.

In addition, the explicitness of the political in the song is different: there is no longer the use of didactic means of denouncing and raising awareness, but the proposition of a syncretic set of disparate images which, while referring to the “Brazilian reality”, at the same time shattered it.

Of course, the reception and acceptance of this music as ‘Brazilian music’ was not easy.

It required audiences and critics to change the way they listened and the way they conceived of what popular song could be, beyond what was fixed by tradition.

So, if on the one hand Tropicalism was enthusiastically received by individuals associated with the search for the new, who valued strangeness as an antidote to the repetition of clichés, on the other it was not accepted by those who considered this movement a distortion of authentic Brazilian music.

Another important aspect is that Tropicalism appeared as a transgression not only because of its musical innovations, but also because it activated behaviors and incorporated them into the very structure of the song, composing a poetics of spectacularity.

The way the artists presented themselves, with extravagant clothes, disheveled hair and provocative and even obscene gestures, made up a language of rebellion, bad taste (by the standards of the time), tackiness and defiance.

In fact, they were assimilating the body into the song, not just the theme, as was common in the tradition. In fact, in this respect, the Tropicalist song goes hand in hand with the assumption of the body that was taking place at that time in all artistic areas.

In the songs, the themes were consistent with the atmosphere generated in the shows: criticism of consumer society mixed with criticism of morals, customs and petty-bourgeois values; criticism of established political positions, right and left; use of popular and erudite cultural residues, forming an apparently chaotic mixture, but actually built according to poetic processes of invention.

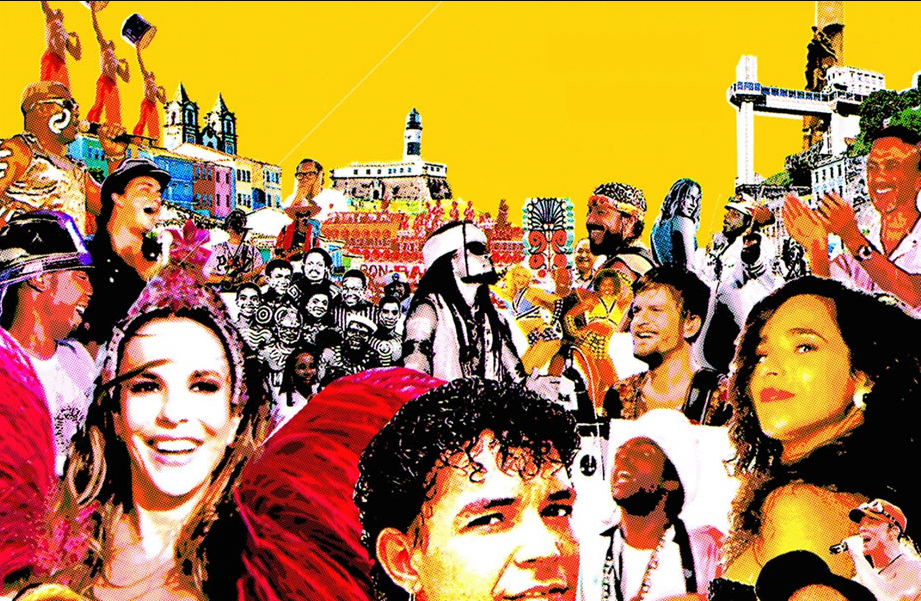

Axé music

Bahia would once again be the cradle of another musical genre in the 1980s, with the creation of axé music, whose precursors were Luiz Caldas, Chiclete com Banana, Daniela Mercury, Timbalada and Olodum.

The genre revolutionized the Bahian carnival, since frevo, a rhythm from Pernambuco, had been used in Salvador’s festivities until then.

Currently, the Bahian music industry is the one that generates the most stars in Brazil and already has a “constellation” with national and international notoriety, such as Ivete Sangalo, who is considered to be the most popular singer in Brazil today and the sales leader in the national music industry, and has the ability to attract a legion of fans wherever she goes, including in international lands.

An example of this was Rock in Rio Lisbon in 2004, where the singer broke attendance records.

Ivete is the owner of Caco de Telha, an entertainment company that is the largest in the North-Northeast and one of the five largest on the national scene.

Caco de Telha has already brought major events to Brazil, such as the I am… tour by pop singer Beyoncé. tour by pop singer Beyoncé, The End tour by the Balck Eyed Peas, The Grand Moscow Classical Ballet show and Cirque du Soleil performances in Brazil.

In addition to these events with international artists, it has also provided the state of Bahia with major concerts with national artists, such as the Roberto Carlos 50 years of music tour.

Through Caco de Telha, Ivete Sangalo was the star of a mega-production at Madison Square Garden, the temple of modern international music.

Bossa Nova

In Bahia, João Gilberto was born, considered among all the other precursors of Bossa Nova: Tom Jobim, Vinicius de Moraes and Luiz Bonfá Bossa Nova, the best-known Brazilian rhythm in the world.

Bossa Nova was a cultural artistic movement created with the aim of modernizing Brazilian music. Tom Jobim is one of the main names.

João Gilberto is considered to be the main creator of Bossa Nova.

Brazil was going through a period of ascension after the Second World War.

The period was known as the “Golden Years”, where economic and cultural growth were developing rapidly.

So, within this optimistic scenario, a group of young people decided to innovate Brazilian culture by creating a movement called Bossa Nova.

In this sense, the movement aimed to incorporate aspects and characteristics of Brazilian music. Furthermore, it is believed that the movement officially emerged in 1958, when João Gilberto released the LP “Chega de saudade”.

Subsequently, other artists such as Tom Jobim and Vinícius de Moraes joined in with various compositions. Among them, one of the most famous Brazilian songs, “Garota de Ipanema”.

In short, the movement was recognized worldwide when, in 1962, a group of artists performed in New York. The event was a concert held at Carnegie Hall.

Among the musicians who took part on the big day were Tom Jobim, João Gilberto and Oscar Castro Neves. Also taking part were musicians Agostinho dos Santos, Luiz Bonfá, Carlos Lyra, among others.

History of Bossa Nova

The movement emerged in the midst of the country’s economic growth. Juscelino Kubitschek (1902-1976) was president and with him political actions such as “fifty years in five” were in force.

With this, the president aimed to put into practice the actions of the Target Plan and the Development Policy.

Therefore, with the economy growing at a fast pace, young people from Rio’s middle class saw the period as an opportunity to create something innovative. So, after various experiments and influences from American jazz, João Gilberto released his first album.

With this, the Bossa Nova movement began, consolidating the musical style in the country.

The movement lasted more than a decade. It ended in 1966 with the emergence of the MPB style, Brazilian Popular Music.

In summary, it is worth pointing out that the end of the movement did not put an end to creations inspired by Bossa Nova. This is because, to this day, musicians still use characteristics of the movement in some compositions.

Characteristics of the musical style

As a way of modernizing the Brazilian music scene, Bossa Nova built its own characteristics that were aimed at the modern style of the Brazil that was being formed. Among the main characteristics that make up the Bossa Nova style we can mention:

- colloquial tone in the voice;

- everyday themes;

- low voice, almost like a whisper;

- Samba harmonies;

- jazz melodic inventions.

As a result, the songs were composed according to the natural manifestations of the streets, the movement of cars, the daily life of the developing urban centers. This gave rise to world-famous songs such as “Garota de Ipanema”. The song was composed in 1962 by Vinícius de Moraes and Antônio Carlos Jobim.

With the coup of ’64, music began to adopt forms of protest against the actions of the dictatorship.

As a result, it was common to see social issues in the artists’ compositions. In addition, it was during this period that what became known as modern Brazilian popular music, MPB, began.

In short, the end of the movement in 1966 did not mean the end of the musical style presented by the artists. This is because, to this day, it is still possible to see compositions that follow the musical style of Bossa Nova.

Main musicians

João Gilberto, Tom Jobim and Vinícius de Moraes were the artists who most marked the Bossa Nova movement. However, besides them, several other musicians also helped to compose great songs.

Therefore, the main musicians are:

- Dorival Caymmi

- Edu Lobo

- Francis Hime

- Marcus Valle

- Paulo Valle

- Carlos Lyra

- Ronaldo Bôscoli

- Nara Leão

- Bebel Gilberto

- Baden Powell

- Nelson Motta

- Wilson Simonal

The main songs of the movement

There were many compositions created in the Bossa Nova style. Thus, they marked the history of Brazil. In addition, some compositions have been recognized worldwide. Thus, among the movement’s main songs we can mention:

1. Garota de Ipanema

This is certainly one of the movement’s best-known songs. It was composed by Vinicius de Moraes (1913-1980) and Tom Jobim (1927-1994). In addition, the song was a tribute to the presenter Helô Pinheiro.

2. Samba do Avião

In short, addressing urban aspects of the city of Rio de Janeiro, the song was composed in 1962 by Antônio Carlos Jobim. Thus, the name came from the musician’s observation that he could see the marvelous city from an airplane.

3.Desafinado

Composed by Antônio Carlos Jobim and Newton Mendonça. However, it was João Gilberto who interpreted it. In short, it was a lyric that mentioned the characteristics of the Bossa Nova movement within the composition.

4.Insensatez

Composed by partners Vinicius de Moraes and Tom Jobim in 1961. The song had melancholic characteristics and a tone of regret. It was a song that took on worldwide proportions and was recorded in English under the title How Insensitive. It was soon interpreted by artists such as Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra and Iggy Pop.

5. Wave

Another composition by friends Vinicius de Moraes and Tom Jobim. It was also produced with the help of Claus Ogerman, who was responsible for the song’s arrangement. The song, which means “wave” in Portuguese, talks about love and beach landscapes.

6.By the Light of Your Eyes

Also composed by Vinicius de Moraes and set to music by Tom Jobim. However, it was in the voice of Miúcha and Tom Jobim that the song became known. So they each interpreted a part of the song. One of the characteristics of this song is that it has no chorus.

7. Ela É Carioca

It was a song composed in homage to the woman from Rio de Janeiro. As such, it was produced by Tom Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes. In this sense, the musicians put aspects of the marvelous city into the lyrics, as well as the personality of the carioca women.

8.Chega de Saudade

In short, it was one of the songs that most marked the Bossa Nova movement. Thus, composed in 1956 by Vinicius de Moraes and Tom Jobim, the lyrics bring love suffering as the main theme. In addition, the name of the song was used to christen the solo album by João Gilberto.

9. Águas de Março

In short, it was a song created in 1972 by Tom Jobim. It soon became recognized in the voice of the composer and singer Elis Regina in 1974. In that sense, it’s considered a big song. However, the song soon became popular and recognized.

10. Samba de Uma Nota Só

Finally, created by Tom Jobim (music) and Newton Mendonça (lyrics), the song has an English version. It is therefore called One Note Samba. In this sense, it is also a song with great lyrics. It also has metalinguistic characteristics.

Did you know?

- The song Garota de Ipanema entered the list of 50 great musical works of humanity. The title came from the US Library of Congress in 2005.

- National Bossa Nova Day is celebrated on January 25, Tom Jobim’s birthday;

- Tom Jobim was considered by the magazine Rolling Stone as one of the greatest names in Brazilian music.

What did you think of the article? If you liked it, go check out Tropicalism, another cultural movement that marked the Brazilian music scene.

Punk / Hardcore

In the 1980s, the first major reference in Punk/Hardcore music emerged in the region of Pernambuco. The band Câmbio Negro HC was the main name, also pioneering the style and producing the first records of the genre in the region, as well as being a major reference in the country’s undergroud music.

Mangue beat

In the 1990s, Mangue beat emerged in Pernambuco, a rhythm that brought together rock, hip hop, maracatu and electronic music. Chico Science and Nação Zumbi are the main names in the genre.

Repente

The repente is widespread in the countryside, with Cego Aderaldo from Ceará standing out. The Banda Cabaçal dos Irmãos Aniceto, a fife band from Ceará, is internationally renowned. Fagner, Belchior and Ednardo, MPB icons, also stand out in Ceará.

Brega

It was also in the Northeast that brega was born, with Pernambuco’s Reginaldo Rossi and Bahia’s Waldick Soriano as its main representatives.

In Maranhão, Northeastern music has a great diversity of rhythms, such as: Tambor de Crioula, Tambor de Mina, Tambor de Taboca, Tambor de Caroço, the four accents of bumba-meu-boi, as well as being one of the main Brazilian strongholds of reggae.

Tribo de Jah, one of the main bands of the genre, originated in the state. Other outstanding Maranhão musicians are: João do Vale; Cláudio Fontana; Rita Ribeiro; Catulo da Paixão Cearense; Lairton dos Teclados; Zeca Baleiro (MPB), and Alcione (Samba).

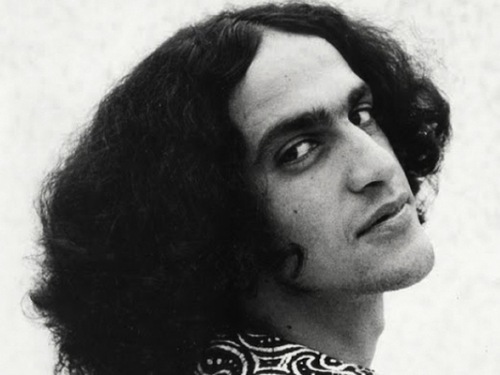

Raul Seixas, born in Bahia, is considered the main name of rock music in Brazil. He was part of the Jovem Guarda movement as a songwriter.

Currently, Pitty, also from Bahia, is very successful in rock music. The groups Cordel do Fogo Encantado and Pedro Luís e a Parede are also making a significant mark on contemporary Brazilian popular music.

The 7 Northeastern rhythms and musical styles that are successful in Brazil.

Genres, Rhythms, Singers and Northeastern Music Composers