Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

Brazil as a Portuguese colony became the new India for the Iberian country. What at the time of its discovery was just a coastline that showed no signs of wealth turned out to be more than that.

Products such as timber, slaves and sugar in the first instance revealed the great economic potential of the territory and created interest in the powers of the old continent.

The realisation of this work starts from the interest in wanting to disseminate and improve subjects little worked on during the degree, in the context of the Portuguese maritime empire.

The choice of the theme was especially due to the great importance that this captaincy had during the Portuguese overseas empire. If there is, in my view, a region to be emphasised during the age of discovery, Bahia is one of those areas and in the work we will see why.

The subtitle shows more than anything the lack of time that this work had for its realisation and as such could not be very specific at the risk of being very time-consuming to execute.

The date of approach between 1500-1697 was a time spacing that I arranged in the course of the work, 1500 because it is the date attributed to the discovery of Brazil, 1697 because it is the date attributed to the discovery of gold.

I decided to use 1697, not because I worked all the way up to that date, but because I wanted to put the brakes on with the launch of this new economy and it was not interesting for this work since it would make the subject too long and because gold took away a lot of political centrality from Bahia.

In this work we will see, general traces of various factors that passed through the history of the Bahia region during the period.

The interest is to try, whenever possible, to resort to sources of the time to be analysed or already analysed.

Captaincy of Bahia de Todos os Santos

Geography

Bahia, Recife, Rio, São Vicente and other ports are all favoured by reefs and coastal strands, giving them distinctive protection.

Bahia is a privileged centre of maritime life; it lies in the middle of two coasts with different characteristics.1 The city is built at the base of an isolated mountain in the region.

The harbour is one end of the city, a harbour protected by reefs, a bay that is an excellent communication route between various lands, a true Mediterranean Sea in its ease of communication.

The Captaincy of Bahia de Todos os Santos at the time it was assigned to the grantee Francisco Pereira Coutinho (1534) had fifty leagues of coastline, from the right bank of the São Francisco River to the current Cabo de Santo António.

The capital of Bahia, the city of Salvador, was built near the old Vila do Pereira which, with the implementation of a general government, became its headquarters (at which time Tomé de Sousa arrived).

Population

Bahia was one of the first points to be discovered by the Portuguese in Brazil.

The Bay of Todos-os-Santos was discovered on 1 November 1501.

It was in this bay that the first European settlers settled, Diogo Álvares plus his companions who were shipwrecked (first proven occurrence).

The division of the Brazilian territory into captaincies adopted by D. João III of Portugal intended the settlement and colonisation of this new territory.

It is known that this was not easy, and this goal was not initially achieved.

In the beginning what we can see are scattered settlement centres along the Brazilian coast, some of which managed to develop (a few) and others stagnated and some disappeared due to various factors.

Bahia in its beginning was also just a set of settlement centres, a captaincy in theory and in the image of Portugal but that the donatary captains failed in their settlement and development, leaving Bahia and not only delivered to the natives until 1549.

Moment when Tomé de Sousa, the first governor-general of Brazil and the founder of the city of Salvador, arrived.

Read Foundation and History of Salvador da Bahia

At the time the Governor-General was established in Brazil, the population began to spread, quite possibly because of the security that the presence of the Governor-General conveyed. Now we see a representative of the king in this colony.

The requests of the population, of the grantees, did not take so long to be met, there was a different kind of response. This created the conditions for Bahia to develop, the nucleus of inhabitants was structured, it grew, it became definitive.

The great obstacle to Portuguese settlement in Brazil was the constant resistance of the Indian.

The search for resources was one of the objectives of the settlement, we saw earlier that Bahia had plenty of brazilwood and that it was of quality, but this was something that was seen without great demand, the settlers were also interested in discovering other riches, as was the case of metals and precious stones, although in the case of Bahia it played a secondary role.

These searches mobilised large numbers of people, which increased the area demographically and allowed communication networks to develop between Bahia and other areas.

Both Bahia and Brazil as a whole took a long time to develop, but when they began to find economic interest in these new Portuguese lands, development increased greatly and competition with other European peoples also favoured them.

The growth of cities is one of the points where we can see this development as well as the population increase.

Let us now look at more specific demographic issues.

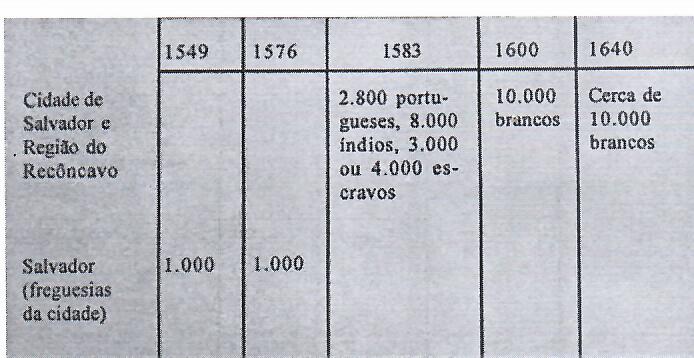

Let’s start with a table that reflects the demographic values of Bahia in various periods.

According to Father Nóbrega, in 1549, the population of Francisco Coutinho had forty to fifty white inhabitants.

As we have seen before, the settlement of Bahia was not easy, in fact, no land in Brazil was completely easy. The main case was the tensions with the natives.

For example, the Tupinambá clashed with the Portuguese when Francisco Pereira Coutinho implemented sugar production in Bahia (cane production).

On 28 July 1541, Coutinho donated two sesmarias (one in the Pirajá estuary to the nobleman João de Velosa and the other in Paripe to Afonso de Torres, a Castilian nobleman).

In co-operation with Francisco Coutinho, sugar mills were established in these two locations.

The enslavement of natives for sugar cultivation was not the only reason for the conflicts between the Portuguese and the natives.

As Father Simão de Vasconcelos says, “peace with the natives of Bahia only lasted as long as their patience lasted, because there was no vile trade, barbarity, violence, extortion and immorality that the Portuguese did not practise against those whom they called savages, but to whom they exceeded in savagery on this point.”

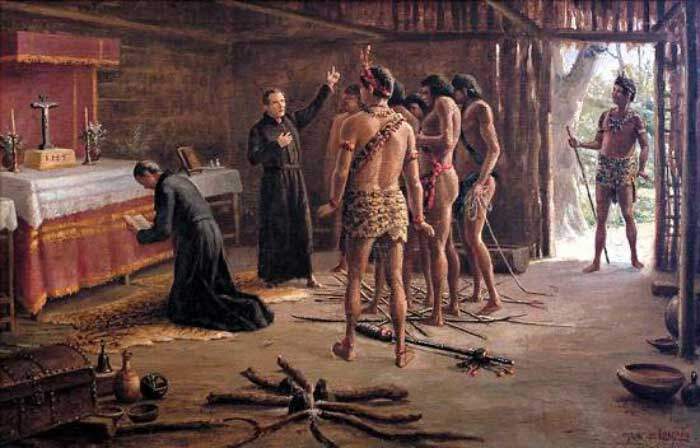

Also the Jesuit priest, Manoel da Nóbrega, reported on arrival in Bahia in 1549 that there was no place where Christians had not caused wars and conflicts, that all the first tensions in Bahia had been caused by them.

Jesuíta Padre Manuel da Nóbrega

The Portuguese occupation of the Bahia-Sergipan region only began to move away from the coast and extend inland from the mid-17th century onwards.

The first reason for this advance inland was the need to find new land for the production of cattle, products needed for the work of the mills and to obtain food to support the population increase.

It was for these main reasons that the hinterland of Bahia was occupied, as was the reason for the excess of Bahian breeders to go and populate fields in other places, such as Ceará, Piauí and Maranhão.

Another reason for the population expansion was the donation of land to sertanistas (a measure to combat the revolted Indians who around 1669 almost reached mills such as those of Jequiriçá and Jaguaripe).

In 1532, Martim Afonso de Sousa informed the king of the risks that the French could offer to the Portuguese colony and this was also one of the reasons that led to the desire to populate Brazil in a more systematic way.

At the organisational level, several parishes, towns and villages emerged, especially from 1680 onwards, such as the parish of Santo António de Jacobina, the parish of Maragogipe and other villages that in the following century would become parishes.

parishes.

In the course of the 17th century, Bahia shared its importance in Brazil with Pernambuco and Rio de Janeiro; they were sort of the three capitals of the State of Brazil.

This was mainly due to the fact that they were among the oldest colonial territories in Portuguese America,

but it was also due to the fact that they were one of the cities that had the greatest economic, political and cultural development;

The other captaincies in comparison had a role at this time, attached, secondary.

When we talk about the settlement of Bahia, we cannot neglect the city of Salvador. The choice of the site for the construction of this city was based on a defensive perspective.

As we will see later, this city was divided (Lower City and Upper City).

In part of it, in the lower city, there was only one street, where the warehouses related to the port and the hermitage of N. Senhora da Conceição da Praia were located.

The original nucleus in the upper city went from the Porta de São Bento to the Praça da Cidade. There were later expansions of this nucleus.

To the north it took the direction of Portas do Carmo and then to the Convento do Carmo (1586).

To the south, it went towards the Mosteiro de São Bento (1584) and to the east we see the first occupation with the construction of the Capela do Desterro (1567).

In the matter of defence, a fundamental part of the construction of the city, the fortifications proved to be fundamental. At first, the lower town was defended by two bastions and the upper town was protected by a fence and a rampart (1551) together with four bastions.

Later, two forts were erected to protect the town, on the bay side, one at Barra (St Anthony, 1583-1587) and the other at Itapagipe (Montserrat, 1585-1587).

When the Dutch entered, they reinforced the two gates and built the first dyke at the present-day Baixa dos Sapateiros.

After the Dutch left, two small forts were built in Barra, at the place where the Dutch landed (Santa Maria and São Diogo) and two more forts to the north, one in Santo António além do Carmo and another in Cidade Alta and São Bartolomeu, in Itapagipe.

A major defence problem of this period was the accommodation of the 2000 soldiers defending the city.

But as it is easy to understand, no matter how many defensive constructions there were, they were unable to neutralise the Dutch offensive and the city ended up suffering bombings, looting, homes were destroyed and the same happened in the recovery of the city by the Spanish troops together with others.

Economy and Food

The initial economic development of the Portuguese colony was very difficult, as was the expansion of settlers into these new lands.

In the beginning the Portuguese witnessed a lack of resources, the human resources they had were also very limited, there were few inhabitants, few Portuguese inhabitants, but worse than that were the great and continuous hostilities of the indigenous people where the Tupiniquins, the Aimorés and especially the Tupinambás stand out as we will see later.

At the time of the arrival of the first captains, the first crops began, possibly mostly manioc production (according to Nóbrega on his arrival in Bahia, this root was the common food that came from the land, it was transformed into flour as well as American corn). The first attempt to produce sugar cane began at this time.

In 1538 a sugar mill was already operating in Bahia fuelled by funds from capitalists/investors from Lisbon. Something that did not survive until the arrival of Tomé de Sousa as we shall see.

It was with the change of policy (implementation of a General Government based in Bahia) that economic activities expanded.

From this time onwards, the extraction of wood was developed and with it the development of shipbuilding, the production of lime, the whale fishing industry was increased and regulated, especially for the interest of their blubber, the cultivation of cotton, tobacco, ginger, cattle breeding was established as well as the number of corrals and the sugar industry was developed.

The following are brief notes on the main resources exploited in the captaincy of Bahia.

Brazilian Wood

The first great Brazilian economic resource or, if we prefer to say, the first product to be exploited with great economic impact, was undoubtedly wood, more specifically the so-called brazilwood.

Brazilwood is a wood that provides colouring matter.

At the time Brazil was discovered, the textile industry was in full development and, as the artificial anilines that we use today were not yet known, brazilwood was a much appreciated and sought after raw material.

It was found on the Brazilian coast, in the forest zone that skirts the coast up to the Cabo Frio area, in relative density.

Afterwards, this extraction was diminished and dragged on, always decadent, for another 200 years, until the progress of chemistry allowed the obtaining of synthetic anilines and, caused the disintention for brazilwood.

The brazilwood cycle was nothing more than a rudimentary exploitation, nothing more than a simple collection, a typical extractive industry.

In the middle of the 16th century, Brazil is still nothing more or less to Europe than the country of coloured wood, a wood used to make precious furniture.

wood used for the transformation of precious furniture and other purposes.

The profitability of this business was such that timber traffickers began to appear in this century.

The Portuguese crown itself reserves the monopoly on the exploitation of brazilwood.

In 1501 we see the first monopoly contract signed for three years with Fernando de Noronha. This is to summarise what timber is economically in Brazil.

As far as Bahia is concerned, we know that there was an abundance of brazilwood, a quality wood, and it was the governor-general of Brazil himself, Diogo Botelho, who in 1606 reminded the king of this fact.

The port of Bahia is one of the major ports and one of the main ports for the shipment of cut timber.

This wood is then usually unloaded in Lisbon unless unusual conditions do not allow it, such as storms or encounters with privateers, which sometimes forces the route to be diverted to another port such as Porto, Viana, Peniche or even another.

The common thing was to arrive in Lisbon and be stored in Casa da Índia.

Cristovam Pires was one of the many commanders, in this case commander of the Bretôa ship that in 1511 came from the Tagus to collect 5,000 logs of brazilwood and various exotic animals in Todos-os-Santos Bay and Cabo-Frio.

Various letters and records allow us to trace typical values of prices on departure from Brazilian ports, values that could have been close to those practised in the port of Bahia.

In 1591 the quintal had a value of around 900 to 1000 réis and in 1666 the value was around 610 réis, of course this was not an ever decreasing phase, during this time there were some increases as it was in 1625 with prices around 1050 réis, this may well have been influenced by the problem with the Dutch in Bahia.

Regarding transport prices, we know that at least between 1602 and 1624 the quintal had a cost of around 300 réis (it is a tax).

The Dutch came to jeopardise the Portuguese trade in Brazilian timber, especially around 1625, much to blame for the effectiveness of the Dutch West India Company and the direct supply from Amsterdam to Brazilian lands, namely Pernambuco.

We have to take into account that the Brazilian timber market was the target of much smuggling, the French even gave serious problems and as a measure to combat this irregular trade so to speak, Abreu de Brito will propose in 1591 the creation of the office of Guarda-Mor and the construction of five fortresses being one of them in Bahia.

Smuggling was so widespread that it was not difficult to conceal the arrival of timber in unauthorised ports, or rather, in ports where the merchandise should not have gone directly.

There is a case reported in the Netherlands in June 1657 by Hieronymo Nunes da Costa, a resident of Amsterdam, who reports the arrival of a shipment of brazilwood from Paraíba.

The governor of Bahia was charged with resolving the problem. The problem of this traffic is quite difficult to solve, especially when certain Portuguese are complicit in these acts, but once these illegal acts are caught, the timber and even the ships can be confiscated and the accomplices are subject to punitive measures.

If the wood from Pernambuco arrives directly in Amsterdam, it does not pass through Lisbon, the wood that comes from other captaincies such as Bahia and that passes through Lisbon before going to Holland, is sold cheaper due to competition, unfair because it is not authorised by Portugal but it is always competition that is reflected in prices and therefore in the profits of the national crown.

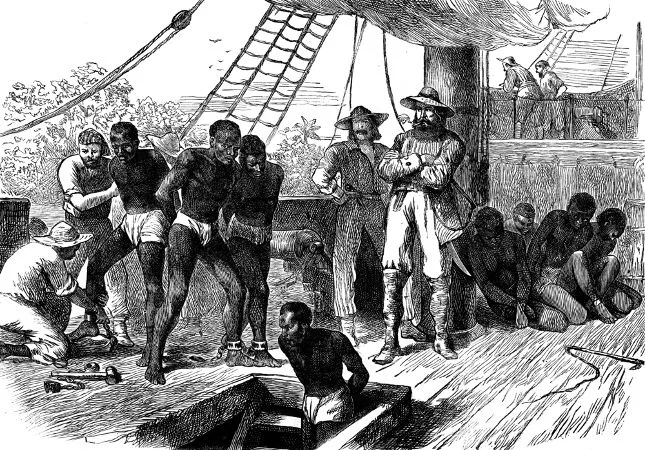

Slaves

When the Portuguese arrived in Brazil it became clear that the Indians would be enslaved, those beings with the shames in sight, did not appear to be useful for anything else, but it was not the question of their ability that was at stake but the need that the Portuguese had.

that the Portuguese had.

Human labour was needed to explore Brazil and the Indian was a resource that was available and it is on this issue that we must base ourselves.

Videos about Slavery in Colonial Brazil

.

Later the Portuguese come to realise that it is a weak resource, much due to the exploitation of sugar. The frequent deaths and lack of profitability lead them to look for a stronger human resource and then they begin to bring slaves from various areas of Africa, most of these land in the captaincy of Bahia.

Effectively, blacks from Africa were the major labour force of the Portuguese economy in Brazil and the dependence was becoming so great that when the Dutch entered Brazil and Angola, there was a time called the Black Famine (1625-1650).

Bahia was taken in 1625, it was one of the main ports of entry for the black slave, Pernambuco was also important and was taken in 1630 not stopping there, in 1640 the Dutch took the Angolan coast from where a large amount of slaves came.

These three points were crucial to affect the slave trade, to the point that in 1644 the Overseas Council receives a request from a certain Sebastião Araújo who wants to go to Guinea to exchange certain goods for slaves to bring to Bahia since in Angola the situation is complicated.

It is curious that while the slave trade is suffering problems as the Dutch try to monopolise this business, sugar cane cultivation is developing with particular incidence in Rio and Bahia. So within the economic spectrum not everything is problematic.

In Bahia there was a very large mixture of Blacks, they were no longer pure Peuls or any other race, it was not a specific and unchanging community, they were more a cluster of mestizos, many had come from Senegambia, Guinea and other African coasts.

There was a desire not to bring a particular group of African peoples together in one place, it was feared that if it triggered certain nationalisms, a native group together could cause revolts and other problems.

This was also only a much-worked issue later in the 18th century, but already in 1647 a letter sent by Henrique Dias to the Dutch reveals the virtues and problems of certain groups of Africans which leads to the conclusion that the best thing was the fragmentation of the various communities by the various captaincies.

This was largely due to the Dutch. Between 1630-1636, few slaves enter Pernambuco, and they begin to emigrate to Bahia to escape the Dutch.

However, although this emigration is seen in this period, it should be noted that between 1600-1630 more slaves entered Pernambuco than Bahia due to the greater number of mills that this captaincy had.

In the 16th century, an estimated 20,000 slaves arrived in Bahia.

During these times the church itself made a distinction between the Indian and the black, justifying that the black should be the slave, thus defending the Indian.

The Church and the orders have always played an important role in native communities.

Sugar

Sugar is the great wealth of Brazil in the 17th century. It gave the Portuguese empire a new source of wealth, somewhat forgetting the riches that at another time came from India.

With the implementation of this new economic structure, focused on sugar, taking into account its production and its needs such as slave labour and the use of the best lands in the northeast, it caused social inequalities, an accumulation of wealth by certain undue and the Dutch invasion (1624- 1625) due to the interest in controlling this business.

Brazil, more specifically the north as was the case of the Recôncavo da Bahia, was endowed with favourable conditions for planting sugarcane plantations. There were fertile, rich soils, some clayey, others consisting of massapé (black earth), endowed with humus (decomposing organic materials).

Bahia thus became, like Pernambuco, one of the most important sugar-producing centres of the Portuguese empire.

As we have already seen, the quality of the soils, the climate (hot and humid), the abundance of forest resources and the favourable condition of the port and the speed of communication with the metropolis were essential conditions for the elevation of the status of the captaincy.

Land for the production of sugarcane and other crops was distributed in the form of sesmarias, with priority being given to land next to rivers and to those who had the capacity to install hydraulic mills.

By installing mills next to watercourses, transport was facilitated (by boat) and the force of water itself was used as a power mechanism for the mill.

When this was not the case and the mills were far from a watercourse, animal and human power had to be used;

Brazil became the main producer of sugar in Portugal, it was even impossible to compete with it, since the middle of the 16th century it was already showing signs of growth in production.

To give us an idea, in the 80s of the same century, an arroba of white sugar in Brazil cost about 800 réis while in Funchal it cost 1800.

In terms of engines in Bahia, we initially have Francisco Pereira Coutinho (donee) trying to build two, something that was not possible because the natives / savages forced the abandonment.

More specifically it was the Tupinambá who united and with about 6,000 men, burned the mills and killed many Portuguese. This war lasted about 5 to 6 years (it must have started in 1541). There were times of great famines, diseases and other misfortunes.

In 1587, Gabriel Soares de Sousa indicated 36 mills for Bahia (21 powered by water, 15 by animal power and 4 under construction).

Around 1610, but without a solid basis for veracity, we can see the captaincy with 50 mills. Not counting Maranhão, there were 235 mills in operation in Brazil by 1628.

In organising the information on mills in Brazil, we can place the captaincy of Bahia in the central zone, which in 1570 had 1 mill, increasing progressively until 1710 when it reached 146 mills (the entire central zone).

The centre zone was not the most profitable, it was the south, not Bahia, it was Pernambuco. In Bahia we see an evolution of mills from 1570 to 1629 from 18 to 84 mills.

The increase in the number of mills was not greater because of the Indians who killed the whites, the Europeans and destroyed the mills themselves, these internal problems were always a constant throughout Brazil.

Torrential rains, droughts, animals, are all factors that jeopardise the development of sugar cane plantations.

In 1665, Lopo Gago da Câmara asked the Overseas Council for a regulation to prevent the movement of flocks in his mill so that the flocks and others would not be eaten.

Sugar exploitation and beyond is subject to taxes (certain tithes), and to make matters worse, the captaincy of Bahia had to pay war indemnities to the Netherlands for 16 years, not the only one with these financial obstacles, but that is what matters for our study.

It seems that the first sugar mills began to be established in Bahia during the government of Tomé de Sousa, but it was only years later, possibly during the government of Mem de Sá, that production reached a point where it was possible to commercially exploit the product and export it in other proportions.

History of sugar cane in the colonisation of Brazil

Fishing and Hunting

According to letters of the time, some of them written to the king by those who were in the captaincy (example of the Jesuit priest Nóbrega) refer that there were many fish, many shellfish, great varieties that served in the food of the local inhabitants.

There was also a lot of game that lived in the bush and birds such as geese that were already bred by the Indians.

The harbour of Bahia has very strict regulations on the sale of fish, and large fish must be sold by weight.

The weights differ depending on the quality.

Bahia set a price for salt fish.

In the years following the arrival of Tomé de Sousa in Bahia, the exploitation of oysters for lime began.

At the end of the 16th century, there were a lot of oysters being taken from Oyster Island which, according to Gabriel Soares de Sousa33, made it possible to create more than 10,000 moios of lime.

Gabriel Sousa also tells us: “And there are so many oysters in Bahia and elsewhere that very large boats are loaded with them to make lime from the shells, of which much is made and very good for the works, which is very smooth; and there is a mill in which more than three thousand moios of lime from these oysters were spent on its works.”

At the turn of the 17th century, freshwater fishing developed greatly. Friar Vicente says: “from there upwards it is fresh water, where there are such great fisheries that in four days they load as many caravelões as go there with fish”.

This refers more specifically to the fishing done in the River São Francisco. For Gabriel Soares de Sousa it is the whale that deserves great attention, he had already predicted that this industry would be successful at the end of the 16th century and this was revealed with the regular establishment of this fishery and with the large quantity of whales that entered Bahia.

Already with the Government-General of Diogo Botelho (1602-1608) assigned by King Philip III, Pedro Urecha brought from Biscay (Spanish region) boats and people with practice in the craft of whaling and its treatment (oil extraction especially) in order to develop this industrial.

This development made it possible to export whale oil to the various regions of Brazil, addressing the shortage of this resource and allowing greater sugar production since, with lighting, some mills could work at night.

INVASORS

French

The French looked favourably on Brazil, wanting to create a centre of influence, especially commercial, where they could extract as much wealth as the Portuguese.

In 1591 Francisco Soares wrote that in 1504 the French arrived in Bahia and that the Portuguese rejected their entry, even detaining three ships.

In fact, many of the corsairs that circulated in Brazilian waters were French, as the Jesuit in Bahia, Leonardo do Vale, said on 26 June 1562, “the new generations of the whole land is to be very full of Frenchmen”.

On the other hand, we see the author Eduardo Bueno mentioning that the Tupinambá had more respect for the French than for the Portuguese.

For them, the French came to Bahia just to collect brazilwood in exchange for other goods, and there were no major conflicts either on arrival or departure.

The Portuguese, on the other hand, had come to stay on their land and were prepared to enslave the natives for their own benefit.

History of Pernambuco and Recife is marked by conflicts

Dutch

The Dutch caused a lot of destruction, they were quite troublesome invaders.

Accounts of the time resemble that of the French when they were invaded by Vikings in the Middle Ages.

Friar Vicente do Salvador (1564-1635) reported that the Dutch, this in the area of Bahia (Rio Vermelho), burned what they found along the way, stole, forced the locals to flee into the bush, threatened and did other worse things.

You can get an idea that the Dutch did as much or more damage than the French in Brazil.

In response to the conquest of Bahia by the Dutch, a Portuguese-Hispanic armada entered the captaincy in 1625 and managed to evict the Dutch from the fort of São Filipe de Tapuype.

Read History of the Forts and Lighthouses of Salvador.

But stepping back, we have to realise why the Dutch showed interest in Brazilian lands.

We are looking at a period when the Twelve Year Truce (1609-1621) had ended and disputes between the Spanish and Flemish had resumed.

On this issue alone, there were no longer any impediments for the Dutch. Then there was the Dutch interest in Portuguese salt and sugar, very important commodities.

In this scenario, the solution to these dependencies was the Dutch occupation of Brazil; there was no need to buy and negotiate with the Portuguese when there was the possibility of getting what mattered straight from the source.

This led to the interest of the West India Company, a private Dutch entity with a lot of rights.

Bahia was the location, the key point for the company to begin its influence in South America.

On 9 May 1624, a fleet of 23 ships and 3 yachts arrived in Bahia ready for the conquest. This fleet was under the command of Jacob Willekens and Pieter Heyn and the 1700 men who landed were led by Johann van Dorth (governor of the lands that were to be occupied).

The governor of Bahia at the time was D. Diogo de Mendonça Furtado.

At this time Bahia did not have enough resources to resist an invasion and the governor was arrested by the Dutch.

The political centre of Portuguese America was thus handed over to the Flemish.

On the advice of Bishop Marcos Teixeira or on their own initiative, many inhabitants fled to other places, namely to the village of Espirito Santo.

It was only in March and April of the following year that, as we have seen, a Portuguese-Hispanic armada arrived to confront the Dutch, with the collaboration of troops from Pernambuco and Rio de Janeiro as well as guerrilla fighting by the inhabitants (“Having on the twenty-ninth of March, the eve of Easter of the Resurrection, launched our Armada at five in the afternoon inside the Bay of the City”).

This collaboration was crucial to the surrender of the Dutch.

Being more detailed in this matter, we know that after the creation of the West Indies, a document was drafted that planned step by step the conquest of Bahia. This document, known as: Reasons why the West India Company

should endeavour to snatch from the King of Portugal the land of Brazil and all that Brazil can translate.

The Dutch aimed to attack three points of the Portuguese empire; Bahia/Salvador, Pernambuco and Angola which would allow control of the slave market.

The first point to be reached was S. Salvador because this city was endowed with a bay with very favourable conditions. It was an excellent point for the control of sugar production and for communication with the slave market coming from Angola.

As we have seen elsewhere in this paper, the governor of the city was Diogo Mendonça Furtado (he had been in office for three years).

He was warned of the arrival of the Dutch armada and as such ordered the reinforcement of the city walls and the construction of a fort on an islet in front of Salvador, where six cannons were mounted.

The curious thing is that when van Dorth ordered the landing on 10 May, he met no resistance. On the same day Pedro Heyn took the newly built fort and several ships moored in the bay.

The first friction with the locals was due to the effectiveness of the Bishop of Salvador in mobilising the population against the Dutch. At this time, Matias de Albuquerque, Governor of Pernambuco and Governor-General of Brazil, sent a caravel with letters from the Bishop to Spain informing of the Dutch takeover of the city.

The news arrived in June 1624, prompting King Philip III of Portugal to order the operation to recover the city and with it the necessary squadron to be prepared in the ports of Lisbon and Cadiz.

Referring again to Tamayo de Vargas, we can see that both the Spanish and the Portuguese were in agreement about the offensive that had to be carried out against the Dutch.

“Not only did Portugal show its normal fidelity and valour in promoting what was necessary to remedy the affliction of the people of Brazil, massacred by the perfidy of the Dutch, who subjected them, to the orders of His Majesty in the fulfilment of the defence of the land, conspiring the noblest spirits in demonstrating their desires and efforts, all coming together on this occasion so propitious to the demonstration of the nobility that set an example for the people to imitate them.

Because, except for a company of about 50 soldiers embarked on the ship N.ª Senhora do Rosário Maior, which was going on behalf of the royal treasury, everything else was due to the voluntary provision with which the loyalty of Portugal served its King, from the ecclesiastics […] and other private individuals […] the businessmen of the Kingdom, the Italians, the Germans and Flemings who traded with them […].

In addition to supplies for the army, ammunition and paraphernalia for navigation, land fortifications and protection against the enemy, and twenty thousand cruzados for whatever was needed at any time, all offered in such good order that, although these things are sometimes only the stuff of stories, in their relations they were proper to the Kingdom of Portugal and an example to all.

To the so heroic use of the treasury of this Crown corresponded its illustrious blood.

For all these reasons, the Council of Portugal, zealous for the service of its King, warns that the rewards for the services of all those who took part in this journey, as well as for their successors or for those who contributed to increase their forces […], were already in their liberal hands.

The armada commanded by D. Manuel de Menezes, its Captain General, and chief chronicler of Portugal, was prepared, consisting of 18 ships and 4 caravels, with everything necessary for the voyage and combat. […]

And many other noblemen exchanged the comforts of leisure for the dangerous restlessness of the sea, because they considered it to be the service of God and their King.

With such brilliance the Armada left the port of Lisbon on 19 November 1624 with specific orders from His Majesty that, as soon as they left, as happened before the Armada of Castile, they should join forces as soon as they could.”.

These armadas were eventually joined on 4 February 1625 in Cape Verde.

We can find these descriptions and others that glorify the image that the Spaniards had at the time for the Portuguese in the work of D. Thomas Tamaio de Vargas, Restauracion de la Ciudad Del Salvador, i Baía de Todos-Sanctos, en la Provincia del Brasi.

This work was dedicated to His Majesty Philip IV, Catholic King of Spain and the Indies & c. It is really interesting to see this work of 1628, there is a great positive trait of the Portuguese people and its analysis is fundamental to understand these issues of the reconquest of Bahia.

Fradique de Toledo y Osorio, Marquis of Villanueva de Valdueza, captain of the Ocean Sea Fleet and of the war party of the Kingdom of Portugal, was the sea and land captain general appointed to take the city (in charge of the amphibious force).

The master general (head of the landing forces) was Pedro Rodriguez de Santiesteban, Marquis of Coprani.

There were six armadas involved in this recovery. We have the Armada de Portugal (22 ships commanded by Manuel de Meneses), as we have already seen, we also have the Armada do Mar Oceano (11 ships, between galleons and urcos, commanded by Fradique de Toledo), followed by the Armada da Guarda do Estreito (4 galleons commanded by João de Fajardo), then there is the Esquadra das Quatro Cidades (6 galleons commanded by D. Francisco de Acevedo), finally there is the Esquadra das Quatro Cidades (6 galleons commanded by D. Francisco de Acevedo). Francisco de Acevedo, and finally the Vizcaya Squadron and the Armada de Naples, the former consisting of 4 galleons commanded by General Martin de Vallecilla and the latter consisting of 2 galleons and 2 patachos under the guidance of Francisco de Ribera and also composed of the Viceroy-Duke of Osuna.

The plan for the recovery of the city was simple and straightforward. “Bring together the Spanish squadrons and armadas with those of Portugal, embark in Salvador de Bahia, recover that square and expel the Dutch definitively from Brazil”.

Apparently it was on 1 April 1625 that the landing took place and the order to attack was given, as well as the siege artillery.

Days after the siege was mounted (30 April), the capitulation was signed, leaving the city with 1,912 Dutch, English, Germans, French and Walloons.

Much had already been taken from the Dutch during the siege, but with the effective victory over them, 18 flags, 260 pieces of artillery, 500 quintals of gunpowder, 600 black slaves, 7200 silver marks and other goods with a rounded value of 300,000 ducats were handed over.

Six ships were also arrested and control of the captaincy was retaken.

Although the Dutch lost this battle for the city, they may have thought the war was not yet lost.

When Fradique was planning his return to Spain, he learnt that a Dutch squadron was coming to contest the Iberian takeover.

On 22 May, 34 sails appeared at the entrance to Todos-os-Santos Bay.

In fact, the Dutch tried several times to penetrate Bahia, but without much success. The lack of effectiveness was also due to the Iberian navy under the command of Dom Fradique, which was unable to neutralise the offensives and this allowed the Dutch to move towards Pernambuco.

Another response could possibly have prevented this event.

The Dutch invasion of Salvador in 1624

Politics and Social Organisation

Bahia, more specifically Salvador, was the first capital of Brazil as a Portuguese colony. It had privileges due to this situation as well as Lisbon and Porto.

São Salvador was a city within the captaincy of Bahia, founded by Tomé de Sousa when he arrived on 29 March 1549 as the first Governor-General of Brazil (given by King João III of Portugal).

This governor arrived on that date with around 1,000 men and one of his aims was to establish a political and administrative centre, a hub that could serve as the capital of the great Portuguese colony.

Together with Tomé de Sousa, the architect Luís Dias was responsible for designing this city, which in the past, along with the rest of the captaincy of Bahia, belonged to the donatory captain Francisco Pereira Coutinho (hereditary captaincy) until it became a royal captaincy.

royal captaincy.

The structural inspiration for this new city was the configuration of Angra do Heroísmo (Azores). There was an interest in following the architectural and structural assumptions of the important cities that the Portuguese were creating along the coasts.

This meant that the new city had to have a good harbour (it already had the natural conditions for this), hills that would favour the city’s defence, drinking water courses and land suitable for cultivation, among other resources.

Salvador was the first city of great political and administrative importance in Brazil, and due to this importance it became from its creation a real fortress city that only succumbed during the arrival of the Dutch.

At the forefront of the city’s formation was the construction of a main square where the governor’s residence, the senate, the pillory and even the jail itself would be located.

The growth of the city wall, largely due to the progressive increase in monastic-conventual houses of the orders that settled in Bahia and the establishment of various centres of population settlement, created a kind of division in the city (division into two parts, one called the lower city and the other the upper city).

The Lower City was mostly represented by commercial and port activities, while the Upper City was characterised by the administration, political, judicial, religious and financial powers.

This urban morphology of the city of Salvador changed with the Dutch occupation in 1624.

When Mem de Sá took over as governor-general in 1558, he was already faced with a Bahia that was larger than the old fortress.

In 1600, he informed the king that “the city is growing considerably”.

In the development of the captaincy, the Indians were incorporated as slaves, as service providers or as captives of the Europeans. At a higher level were the Portuguese who came to Brazil: feitores, mechanical officers and sugar masters, who were particularly prominent because they generated a large income. Among the rural landowners, the farmers and small cattle breeders occupied a rather thankless position.

Standing out from everyone and everything were the engenho lords (wealthy landowners with their own estates).

The city of Salvador was the first to be created in all of Portuguese America.

From the beginning it had well-established communication routes. Until very late, most of the houses were of the primitive type, simple dwelling places covered with palms in the image of the first houses to be built in Brazil.

Between 1549 and 1551, a Santa Casa da Misericórdia was set up in Salvador with the main objective of curing and treating the poor and sailors.

sailors.

This institution, according to Gabriel Soares, did not have large workshops or infirmaries, and was poor, possibly because it had no royal or private contributions; the only support it had was alms from the local inhabitants.

In 1556, the Jesuits also established a college in Bahia which had three courses: one of letters or elementary education, the other of arts and theology for ecclesiastics and higher students.

As a result of the demographic expansion into the hinterland, the development of agriculture and livestock farming, new social typologies began to be defined, with the Vaqueiro and Fazendeiro appearing in Brazilian Portuguese terminology.

The privileged (mostly plantation owners) began to be more clearly differentiated from the free men without resources and from the captives, namely slaves.

If we go further and look at the administration, we will see the representation of mechanical officers in the sessions of the Senate of the Chamber as well as the creation of positions of procurators of the masters which also allowed the election of a judge of the people and of slavery (royal charter).

slavery (royal charter of 28 May 1644) was an example of this.

The number of these posts increased and these judges increasingly acquired powers that until then had belonged to the councillors.

The appearance of representatives of the mechanical officers in the administration changed the mentality of the people towards power, creating greater popular resistance to central power. These political changes and the rise of class-elected mechanical officers to the Chamber of Aldermen of Bahia were part of the demands of the people who, in the future, particularly in the 19th century, came to have a nationalist reaction and collaborate with

nationalist reaction and collaborate with the pressure for the independence of Brazil.

In terms of courts, the first was created in Bahia in 1603 by King Philip II of Portugal, under the title of “Relação do Brasil”.

In 1626, by the will of King Philip III of Portugal and with the creation of the “Relação de Rio de Janeiro”, the court in Bahia was renamed the “Tribunal da Relação da Bahia”, and the captaincy of Bahia itself, but also that of Sergipe, Pernambuco, Rio Grande do Norte, Paraíba, Ceará, Maranhão, Pará and Rio Negro, came under its control, if we prefer.

Analysing the changes in politics in Brazil, we can conclude that the implementation of the Hereditary Captaincies was a failure which led the Portuguese crown to implement a General Government and the creation of the city of Salvador by the bay of Todos-os-Santos as the

political centre.

In the initial period, with the arrival of 1000 inhabitants together with Tomé de Sousa, the Portuguese crown intended to create a new and fortified city, where these inhabitants who moved in, officials, religious, military, builders and others, could establish institutions to administer the city.

others, could set up institutions to administer Brazil.

One of these institutions was the Governo-Geral, which was the crown’s representative in the colony and the main responsible for its defence, another of the most important institutions was the first Court of Appeal, established in 1609 and extinguished by the Spanish in 1625.

Captains and other prominent political figures Let’s start with Diogo Álvares Correia, better known to the indigenous people as Caramuru.

He was not a captain but was probably the first Portuguese lord in Brazil. According to the account of Juan de Mori, pilot of the Spanish ship Madre de Dios which was shipwrecked in the vicinity of the Bay of Todos-os-Santos and which was assisted by Caramuru, and also according to a statement by a certain D. Rodrigo de Acuña (1 July 1526) who was the first to mention the presence of Diogo Álvares in Bahia, confirm that Caramuru was in Brazil from the end of 1509, when he was shipwrecked in the shallows of the Rio Vermelho on a possible French ship.

Although Caramuru travelled to France in 1528, he returned to Bahia to continue his involvement in trafficking and smuggling.

In practice he turned out to be a kind of “commercial agent for the French paude-tinta smugglers”. Diogo Álvares’ time as lord of those lands that were never his effectively ended when Francisco Pereira Coutinho arrived in Bahia around November 1536 with seven ships and the title of legal owner of those lands.

This did not prevent Francisco Pereira Coutinho from donating a sesmaria to Caramuru on 20 December 1536.

Francisco Pereira Coutinho was the son of Afonso Pereira, alcalde-mor of the Portuguese city of Santarém. He was the first captain donee of Bahia55 (5 April 1534) and the second donee to receive a plot in Brazil.

He arrived in Brazil, as we have previously seen, in 1536. On arrival at his captaincy, he slept for days on the ship until a settlement was built to house him and the rest of the crew.

Everything suggests that Francisco Pereira Coutinho was enthusiastic about these new lands, as we can see in the letter he wrote to the king in 1536.

“This is the best and cleanest land in the world… It is bathed by a river of fresh water as big as Lisbon, into which as many ships as there are in the world can enter, and there has never been a better or safer harbour. The land is very peaceful and, a league away, there is a village with 120 or 130 very meek people who come to our houses to offer rations and the principle of them, with his wife, children and people, already want to be Christians and say that they will no longer eat human flesh and bring us supplies … The fish is so much that it goes for free and they are fish of 8 palms … The coast has a lot of coral … The land will give everything they throw into it, the cottons are the most excellent in the world and sugar will be given as much as they want.”. Bahia, like other captaincies, did not always remain prosperous.

Francisco was unable to adapt to the demands and there was much friction between him and Diogo Álvares. 57 It was at the height of tensions between the Portuguese and the natives that Francisco Coutinho fell from his post.

On 20 December 1546, Duarte Coelho, who was in charge of the captaincy of Pernambuco, sent a letter to King João III about the problems that were occurring in Bahia. João Bezerra was a Portuguese cleric who contributed greatly to the movement against Francisco Coutinho.

He was a despicable cleric who earned the king’s notice from Duarte Coelho and Father Manoel da Nóbrega. During this time of high tensions, the French and Diogo Álvares continued their heavy-handed attacks on the brazilwood trade. Francisco Coutinho was eventually captured along with other elements by the Tupinambá, where they were killed and the captain himself was even eaten by the natives.

As we have already mentioned, Francisco Coutinho was the first to be appointed captain of the captaincy of Bahia. At this time, in the matter of appointing governors for the captaincies, it was normal to appoint an old nobleman who had distinguished himself since the time of King Manuel.

Manuel.

Francisco Coutinho was an example of this, he was a “very honourable nobleman, of great fame and knighthood in India”. In fact, he served with the Admiral Count Vasco da Gama, with the Viceroy Francisco de Almeida and with Afonso de Albuquerque.

As we have seen, Coutinho did not lack experience, he had an eventful life but was still powerless in maintaining the captaincy of Bahia. Francisco Coutinho was one of the last captains to arrive; there were about two years between the letter of donation and his actual arrival in the colony.

Finally, let’s look at Tomé de Sousa, who was not a grantee of the captaincy of Bahia, nor governor of the Chamber, nor was he a pioneer in colonising the territory, but he was responsible for building the city of Salvador and therefore deserves this highlight.

Tomé de Sousa, a member of noble lineage, served in Arzila between 1527 and 1532, went to India (1544) and in December 1548 at the request of King João III became the first Governor-General of Brazil with broad powers to govern the colony.

With him came a detailed regiment for administering the lands. He had the city of St Saviour built on the bay of Todos-os-Santos.

In 1550 the city already had a town hall where Tomé de Sousa’s rank as Governor-General was recorded.

This governor, unlike the captain Francisco Coutinho, knew how to relate to the Indians and had close relations with Diogo Álvares Correia, a Portuguese with great prestige among the Tupinambás (the largest Indian nation on the coast and in the neighbourhood).

With Tomé de Sousa also came Father Manuel da Nóbrega with his Jesuit co-religionists who initiated a mass Christianisation of South America.

Tomé de Sousa was a supporter of the Jesuits and a protector of the newly converted Indians. He returned to Portugal in 1533 receiving honours from King John III, became vedor of his household and treasury lasting until the government of King Sebastian. He died in 1579.

Church

Before we talk about the Church itself and its foundation in Brazilian lands, we must understand that several religious orders entered Brazil, either by royal initiative or by the initiative of the order itself.

With the arrival of Tomé de Sousa, the first Jesuits also arrived, led by Manuel da Nóbrega, who created a chapel and a boys’ school. In 1582 the Benedictines arrived and in 1665 the Discalced Carmelites;

Between 1514 and 1551 several churches and parishes were founded in various captaincies, with their own vicars, curates and chaplains.

In 1551 there was still no church in the city of Salvador, which would be elevated to cathedral status. On 31 July 1550, King João III asked the head of the Catholic Church to create the first bishopric.

“In the lands which are called Brazil there is a great number of Christians, and there are churches in which the divine offices are celebrated and the sacraments are administered. And there is hope that many of the unfaithful and barbarous people will be converted to our holy Catholic faith, of which there is already much beginning. And because for the good government of the spiritual it is necessary that in those parts there should be bishops who will govern the clergy and people, and indoctrinate and teach the said people in the things of our faith, I ask Your Holiness to want to create again in cathedral see the church which is called the Saviour, in the city otherwise called the Saviour…”.

On 25 February 1551, Pope Julius III issued the Bull Super Specula Militantis Eclesiae which allowed the creation of the diocese of S. Salvador da Bahia, the first in Brazil.

At this time the Spanish church in America was much more developed than the Portuguese.

In the overall picture of America (including Portuguese and Spanish territory), the city of Salvador was the 23rd diocese and the 5th archbishopric in America in 1676.

Salvador was only the first city and the first diocese in the Brazilian context.

The bishopric created by the aforementioned Bull was the bishopric of St Salvador of Bahia, not of Brazil.

The territories of the other captaincies did not belong to the Diocese of Bahia. On 7 December 1551, in the presentation of Pedro Fernandes Sardinha to Tomé de Sousa and others, King João III confessed that he had asked the Holy Father that, until other bishoprics were created, the Bishop of Salvador should have powers and jurisdiction over the remaining lands of Brazil.

The city of Salvador did not have the title of diocese of Brazil but it was effectively the centre city. It was the capital of the Archdiocese of Brazil from 1676 until 1892 when the Archdiocese of Rio de Janeiro (the second in Brazil) was created.

Several religious orders came to Brazil, some on their own initiative and not at the request of the Portuguese king. The missionaries of the Society of Jesus were among the first and had the greatest presence.

The first ones arrived with Tomé de Sousa, and the main character, or superior of this group if we prefer, was Fr.

Manuel da Nóbrega. In 1570, they already had convents in the Bay of All Saints as well as in Ilhéus and Porto Seguro.

In 1552 Bishop D. Pêro Fernandes Sardinha. Several villages were governed by the Jesuits in this captaincy, villages very much in contexts of survival. Villages such as Espirito Santo (1556), Vera Cruz or Santa Cruz (1560), Nossa Senhora da Assunção de Macamamu, São Tomé do Paripe and Porto do Tubarão.

Conclusion

This work, although not very in-depth or selective in certain aspects due to the lack of time for its preparation, is sufficient to show the centrality and importance of Bahia for the Portuguese maritime empire and beyond.

Firstly, we conclude that the first fixed Portuguese presence in the region was not organised; in fact, we see a man called Caramuru by the indigenous people, plus his crew, who settled in the region after a shipwreck. This Portuguese was the first to create sustainable relations with the Tupinambás and beyond.

These Indians and even Caramuru himself were responsible for the failure of the government of the donatory captain Francisco Pereira Coutinho and the constant destruction of mills.

Secondly, we conclude that this area had one of the most favourable ports for navigation and communication with other places, it maintained very favourable routes both to the metropolis and to other places such as Angola from where black slaves came, both in Portuguese and Dutch times and also on clandestine trade routes (we saw that resources such as brazilwood reached Amsterdam without passing through Lisbon first).

Thirdly, we can see the great economic development compared to other captaincies in the development of mills and the extraction of brazilwood of various kinds.

Bahia had a large forest. Its proximity to the ocean and fresh water courses favoured the region in fishing.

Fourthly, we have seen an administration with several changes.

After the failure of Francisco Coutinho, we see Tomé de Sousa with the title of Governor-General founding the city of Salvador and developing not only Brazil but Bahia specifically, much under the guidance of his regiment. We see the church taking its developments, forming its structures and having its primary centres in Bahia.

Finally, the French and Dutch invasions should be emphasised. The French corsairs were early on trying to acquire for themselves some profits from the traffic in Brazilian goods; but it was the Dutch who had the worst connotation, it was they who created the most

damage, who looked on Bahia not as a trading post but as a settlement.

They wanted to control everything, from sugar production to its trade to the slave market in order to retain all the profits for themselves.

At this time, Portugal was part of the Spanish monarchy, we had the Philippine dynasty in force and it was with attacks by joint Portuguese and Spanish forces, and even with the support of other allies, that it was possible to recover the city of Salvador and beyond. There are those who believe that the bad strategy taken against the Dutch led the Dutch, instead of giving up on Brazil altogether, to try other centres of settlement, as was the case in Pernambuco.

As expected, this work failed to mention colonial taxation, taxation and financing, the Royal Treasury, the Chamber and the Treasury, among other issues.

Captaincy of the Bay of All Saints – Settlement, Economy and Politics between 1500-1697 – History of Brazil