Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

Carnival, a festival of ancient Catholic tradition originating in Europe, is held annually in the three days before Lent.

Introduced in Brazil by the Portuguese colonizers, it was known as Entrudo in the first centuries of colonial life. During this period, games were played with limes and lemons, or throwing powders and containers of water and other liquids at each other.

The games were played between families in the manor houses or in the streets and squares where slaves and poor free men usually played.

During the Empire, the festival dedicated to laughter and pleasure was more commonly called Carnival.

The urban elites gradually abandoned the Entrudo toy and turned their eyes to the carnivals of the most progressive cities in Europe, such as Nice, Paris, Naples, Rome and Venice, where the revelry was animated by balls, dances, music, illuminated halls, banquets, parades and parades of masks and luxurious costumes through the streets of the cities.

Videos about the History of Carnival in Brazil

Carnaval na Bahia

História do Carnaval no nordeste

Aprenda a fazer um turbante

Carnaval em Pernambuco

Festa de Carnaval nos estados do Brasil

These entertainments were seen as a sign of civilization and progress, of elegance and cultural advancement.

From the mid-19th century, carnival societies emerged, formed by members of the urban socio-economic and cultural elites whose members showed off masks, parading in floats and criticism.

Criticizing customs, politics and social types through laughter and humour without committing personal offences was a highly valued practice. Salvador, in Bahia, had the Bando Anunciador dos Festejos Carnavalescos, the Cavalheiros do Luar and the Cavalheiros da Noite, whose members were young men from commerce and some writing clerks.

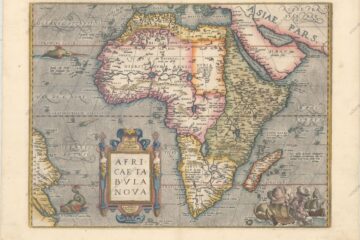

In the 1890s, black clubs appeared, parading in luxurious cars of criticism and ideas, accompanied by a charanga made up of African instruments. Their names referred to Africa: African Embassy and Pândegos d’África, African Arrival and Warriors of Africa. These large black clubs were a particular feature of Salvador’s Carnival.

In Recife, the Carnival of masks, criticism and allegories was represented by the carnival societies Asmodeu, Garibaldina, Comuna Carnavalesca, Azucrins, Os Philomomos, Cavalheiros da Época, Fantoches do Recife, Clube Cara Dura, Seis e Meia do Arraial and others.

In 1883, the Francisquinha Club made the joy of the street carnival of São Luís do Maranhão. With a more marked presence in the revelry of Momo from the 1870s onwards, the clubs of allegory and criticism went into frank decline in the early years of the 20th century.

The popular classes, in turn, continued to occupy the streets with their toys and amusements, being the object of contempt from the elites, criticism from the press and police repression – segments that saw them as a sign of ignorance and socioeconomic backwardness and as a potential danger to public order.

In Recife, in addition to Entrudo, the “populacho” indulged in sambas, maracatus and cambindas, and entertained themselves with the King of the Congo, fandangos and bumba-meu-boi.

In São Luís, at the end of the 19th century, there was a proliferation of bards – a band of blacks painted white, carrying umbrellas or umbrellas – and strings of bears, puffins, bats, deaths, dirt and other animals such as guarás, rams, eagles.

In the revelry of Salvador, the “caretas” appeared wrapped in catolé mats or with tree leaves covering the abadás; in addition to the caricature of Ioiô Mandu, a costume made with a petticoat, sieve, broom handle and an old jacket.

In 1905, in order to avoid the so-called “Africanization” of Salvador’s Carnival, repressive measures were intensified against popular street carnival revelry, which included batuques, sambas and candomblés. Until the early 1930s, there were no known reports of clubs or blocks that evoked Africa or performed batuques in the central streets of the Bahian capital.

In Recife, from the 1880s onwards, the decade in which slavery was abolished and the Republic proclaimed in Brazil, the number of popular carnival groups in the streets multiplied, formed by urban workers, artisans and craftsmen, laborers, salesmen, market vendors and domestic workers.

When they performed in public, they attracted all sorts of people: idlers, vagrants, street kids, capoeiras.

Among the pedestrian carnival clubs, those that were accompanied by brass bands or orchestras that performed the vibrant carnival marches, later known as marchas pernambucanas and finally as frevo, predominated: Caiadores, Caninha Verde, Vassourinhas,Pás, Lenhadores, Vasculhadores, Espanadores, Ciscadores, Ferreiros, Empalhadores do Feitosa, Suineiros da Matinha, Engomadeiras, Midwives of São José, Cigarreiras Revoltosas, Verdureiros em Greve, amidst many others.

The frevo and the Pernambuco step were born in the back and forth of clubs and troupes. At the beginning of the 21st century, it was agreed that frevo was born in 1907, the year in which the first record of the word frevo was found in a local newspaper, Jornal Pequeno, in the edition of February 9, 1907.

The maracatus nations, with their loas and bombo toadas, also considered by the elites as dangerous, infectious, producers of “an infernal noise”, began to be more or less tolerated by the Pernambucan elites from the 1920s and 1930s, perhaps because they referred to the traditional ceremony of the King of Congo and the fact that some exhibited themselves “visibly organized”.

Blacks, mulattos and caboclos also sought space in the revelry organized in the Caboclinhos, groups that performed with music, dances and clothing that evoked the self-hieratics used by Jesuit missionaries in the catechesis of the Indians: Canindés Tribe (1897), Carijós (1899), Tupinambás (1906) and Taperaguases (1916).

From 1930 onwards, the process of officialization of Carnival in Brazil began and cultural manifestations originating from the popular strata began to be recognized as the great force and expression of Carnival. In Recife, the Federação Carnavalesca Pernambucana, founded in 1935, became responsible for organizing the festivities and defined the categories of street carnival associations: clube de frevo, troça, bloco, maracatu nação or de baque virado and caboclinhos.

The popular bears and oxen of Carnival and the maracatus de baque solto were excluded from the list. During this period, frevo was officially considered a symbol of Pernambuco’s cultural identity.

In São Luís, in 1929, batucada groups or blocos emerged that recovered the traditional local rhythms. In Salvador, the popular Carnival regained momentum in 1949 with the creation of the Afoxé Filhos de Gandhi, a group formed by dockworkers and linked to Candomblé.

In the 1950s, the municipalities of Recife and São Luís took over the organization of their respective Carnivals and instituted official competitions between the different categories of carnival groups.

Their intention was, among other things, to turn Carnival into a tourist product and a great open-air spectacle. The appearance of the trio elétrico, which radically changed the structure and form of Salvador’s carnival celebrations, dates back to 1951.

In the 1980s, electric trios were seen animating Carnivals and Micaremes, the so-called “Carnivals out of season”, in several Brazilian cities.

During the years of the military dictatorship, the street carnivals of Recife, Salvador and São Luís almost disappeared. They began to regain strength and energy with the first signs of political openness from 1975 onwards. In Pernambuco, celebrations exploded in the streets of Olinda, where carnival clubs showed off in the midst of the people, without the parades, catwalks and official competitions.

In 1978, in Recife, the O Galo da Madrugada Mask Club was created, which would become the largest carnival organization in the world, as recorded in the Guinness Book of Records, at the turn of the 20th to the 21st century.

In São Luís, driven by the growth of the Black Movement, the first blocks of Afro-Brazilian cultural matrix appeared around 1984 and, since the 1990s, Carnival has shown its vitality through cultural expressions of local roots.

In the city of Salvador, the Filhos de Gandhi and Ilê Aiyê, created in 1974, have established themselves as great expressions of blackness, contributing to the process of preserving, strengthening and valuing the ethnic and cultural identity of Afro-descendants and giving positive meaning to the so-called “reafricanization” of the Carnival of Bahia.

Afoxés and blocos de negros today share the avenues and the attention of the public and the mass media with the trios elétricos and the blocos with their abadás and cordões de isolamento. By the end of the 20th century, the Bahian festival had become a profitable commercial enterprise, subject to the logic of the market, although many still seek it out simply to laugh, have fun and play.

When he wrote the first lines of the novel “Gabriela, Cravo e Canela” at the end of the 1950s, writer Jorge Amado had no idea that this character of breezy beauty and skill in the arts of seduction and cooking would become one of the main cultural icons of the city of Ilhéus, which is located 405 km from Salvador.

Walking through the streets of the quiet municipality bordered by the sea and a vast area of Atlantic Forest, it is possible to get a sense of what Ilhéus was like in the 1920s, so well narrated by Amado.

In the city center, commerce is thriving and the houses still retain the luxury and dimension of what was the golden age of cocoa farming, which succumbed to the plague of witches’ broom in the late 1980s.

From the period of the colonels and the abundance, when cocoa was considered a bargaining chip for large financial transactions and the amount of land and properties represented power and a sign of wealth, some symbols have been preserved and remain active today.

One of them is the centenary Bar Vesuvio, which in the novel belonged to the Turkish Nacib, a character who lives a story of passion with Gabriela.

The other is the Bataclan, a famous brothel, owned by the pimp Maria Machadão, where in the past the cocoa barons went to have fun or drown their sorrows and today is a restaurant that opens from Monday to Saturday for lunch, dinner and musical and cultural programs.

The extravagance of the powerful is also portrayed in Rua Antonio Lavigne de Lemos, which allows access between the two main churches of the city: the Cathedral of São Sebastião and the Church of São Jorge, patron saint. Several dozen meters are paved with cobalt stones, paving sponsored by the millionaire Misael Tavares, who today gives his name to a palace.

Articles related to carnival

- History and Chronology of the Carnival of Salvador de Bahia

- .King Momo, Pierrô, Harlequin and Colombina – Carnival Characters

- Maracatu rural at the Carnival of Nazaré da Mata in Pernambuco

- Barreiras has Micareta which is an off-season carnival that attracts the young

- .The Salvador Carnival is the biggest popular event in the world

- .History of Salvador Carnival

- Origin and History of Carnival in Brazil

- The 7 Northeastern rhythms and musical styles that are successful in Brazil

History of Carnival in Northeast Brazil