Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

From 1500 to 1822, from discovery to independence, Brazil exported goods worth a total of £586 million.

In this total of values, to which production does the largest contingent belong? Gold, one might answer. No: gold contributed only 170 million.

Coffee only started at the end, and in our balance of trade it weighed less than rice, cotton, tobacco, wood, hides, and only a little more than cocoa..

Its export, in the colonial period, did not exceed four million in total.

There was, from the discovery to independence, a product that, alone, yielded more than all the others combined, including those of mining: sugar, of which we exported 800 million pounds sterling”. Luís Amaral, história geral da agricultura brasileira v. 1, p. 326, 1958.

The purpose of this text is to show how sugar from the sugar cane arrived in Brazil, how the sugar cane plantations and mills were structured, how sugar was manufactured, as well as to tell a little about Brazilian economic history in the colonial period, a time when sugar in the 17th century became the “white gold” of the Portuguese colony.

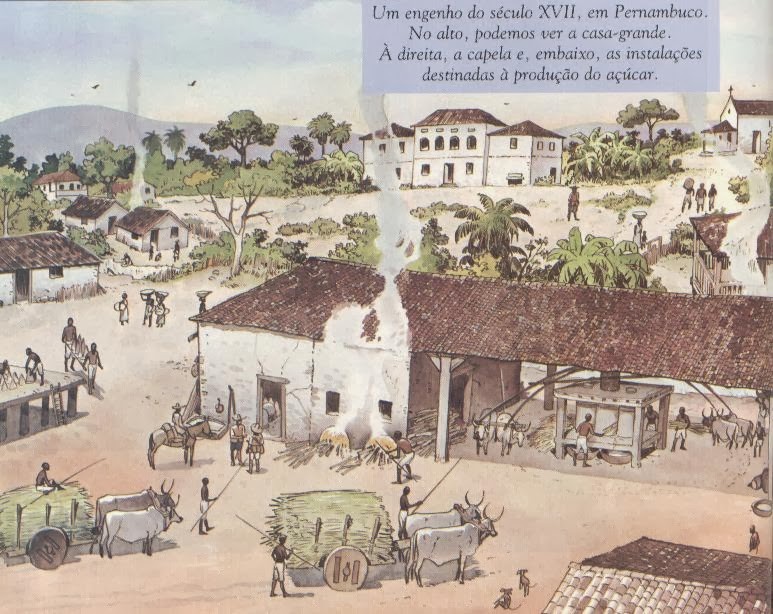

One of the best accounts of sugar production and manufacture was written by the Italian Jesuit Giovanni Antonio (1649-1716), who, living in Brazil, adopted the name André João Antonil. In 1711 he published in Lisbon his book, Cultura e Opulência no Brasil por suas drogas e minas.

In this book he comments in detail on the reality of sugarcane cultivation, the structure of the sugar mill and the manufacture of sugar, based on the mills of Bahia at the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century.

The original book has more than 200 pages, although it also deals with tobacco production, gold mining, livestock, etc. The first part of the book is dedicated only to dealing with sugar. To those interested I recommend reading this book which has versions in current Portuguese.

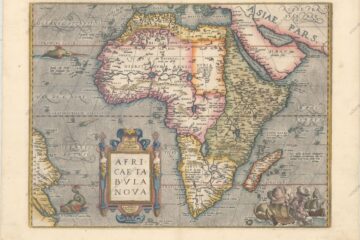

Sugarcane from Asia to the Americas

Originally there were six species of Saccarum, the scientific name for sugarcane.

The first species to be domesticated was the Saccarum officinarum, which over the centuries and the increase in interest in the cultivation of this plant, led to hybridization between species, leading to the creation of hybrid species, which had better characteristics than the original plants.

Crossbreeding between species in plant cultivation or animal husbandry is common and quite old, as humans noticed that certain physical characteristics could be transmitted by crossing. It is worth remembering that this idea arose long before the conception of DNA, genetics, phenotype, etc.

Another curious fact is that sugarcane belongs to the Poaceae family, a family to which corn, rice, sorghum, wheat, barley, rye, oats, bamboo, etc. belong.

“The sugar cane does not reach the height of a tree, but that of corn and other canes, rising in calamus from seven to eight feet, an inch thick. It is spongy, juicy and full of a sweet, white core.

The leaves are two cubits long, the flower is filamentous and the root is soft and not very woody. It produces shoots for the hope of a new crop. It likes moist soil, warm climate and tepid air. West India is very fierce with these canes, although East India also produces them”.

Sugarcane originated on the island of New Guinea, from where it spread to the Malay archipelago, Indonesia, until it migrated to the continent, settling in India and Southeast Asia in countries today such as Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and southern China.

In India we find mentions of the cultivation of this plant and its ritualistic use in some ancient texts, for example, in the Mahabharata, an important Hindu poem, there are mentions of sugar cane, including that the god of love Kama, had a bow made of cane. Is that where the idea that love is sweet comes from?

Sugarcane has been cultivated for centuries by different Asian peoples, but it is not certain when it migrated to West Asia.

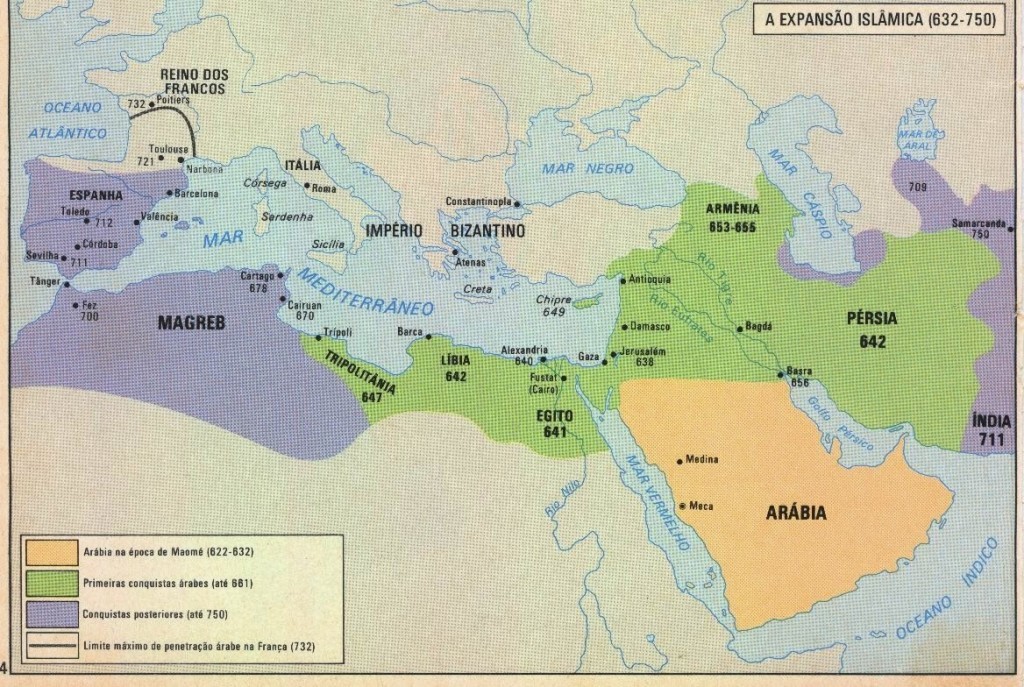

Amaral [1958] had pointed out that sugarcane would have been taken to Persia in the time of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC, since we know that Alexander made incursions to India. And from Persia the plant would have reached Syria. However, its distribution throughout the Middle East occurred with the Arabs, centuries later, in the Middle Ages.

With the expansion of the Islamic empire of the descendants of the legacy of the prophet Muhammad (570-632), at the end of the 11th century Christian Europe came into conflict with the Arab world, the main reason, the conquest of the holy city of Jerusalem.

As the Crusades unfolded, Europeans had contact with new plants, animals, peoples and cultures, and one of these contacts was with sugar cane which attracted the interest of some Italian merchants, who took some seedlings to be planted in Sicily and on the island of Rhodes.

In addition, Arab expansion led these desert people to enter Egypt and spread across northern and eastern Africa.

In what is now Morocco, the Arabs crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and entered what is now southern Spain.

In the following centuries they expanded their domains in the Iberian Peninsula, ruling large parts of the current territories of Portugal and Spain, and with this colonization, they implanted the cultivation of new plants: oranges, lemons, tea, including sugar cane.

The Arabs, who mixed at that time with Berber peoples from North Africa, came to be called Moors by the Spanish and Portuguese. In Italy, Greece and the Holy Land, Europeans also called the Arabs Saracens.

Sugar was long used in Europe as a medicine, in which case physicians recited its pure consumption, or it was used as an ingredient in the manufacture of potions, pastes, drinkings, etc. Although it does not have efficient healing properties, sugar with its high sucrose content is a natural energizer.

“It served as a medicine, a poultice, a coin and even as an agent for black magic, with witchcraft and chiromancy.” According to Thevet, “les Anciens estimerent for le sucre de l’Arabie, pour se qu’il estoit souverain… en médecines, mais aujord’huy la volupté est augmentée jusques là que l’on ne saurait faire si petit banquet que toutes les saulces ne soyent sucrées, et aucune Pois les viandes”.

“The juice of the former is to be praised for its cleanliness and usefulness, and this usefulness is known to kitchens and pharmacies, the healthy and the sick, for sugar serves as food and medicine. It is, after butter, a treat for our diet and a pleasant stimulus to gluttony in sweets and desserts”;

Even today there are medications that use sugar in the recipe, for example, homemade serum takes sugar and salt in its preparation.

But today it is known that in large quantities it is very harmful to health, however, in the Middle Ages and the Modern Age it was common to use what we call today alternative medicine, so we have a multitude of natural medicines that used the most diverse types of ingredients, which resemble the miraculous magic potions seen in literature, films and drawings.

With sugar it was no different. Barléu [1940] briefly recounts that sugar in ancient times was used as a remedy for stomach, intestinal, liver and other ailments.

In addition to being used as a medicine, sugar was also used in the preparation of food and drinks, after all it was one of the spices of the Indies. Therefore, we see in some countries such as Portugal, the Hispanic Kingdoms (Spain was only unified at the end of the 15th century), in the Italian city-states, in France and England, nobles or rich merchants giving chests with sugar as a gift, something considered a luxury gift.

“In the past, a loaf of sugar (each loaf was just over two kilos) was listed as a precious possession in royal treasuries. The product of the sugar cane was attributed miraculous virtues for health. Seven loaves of sugar (14 kilos) left the wife of Charles V of France in her will, among precious jewels.

And the king’s successor gave another sovereign a few more kilos of the magical commodity as a royal gift.” At the time of the discovery of Brazil, Europe took everything with sugar: meat, wine, fish.” (AMARAL, 1958, p. 327).

In England of the Tudor government in the sixteenth century, sugar was so expensive that only the rich bought it.

A curious fact is that as people did not have the habit of brushing their teeth, or using another means to clean them, so consuming sugar and sweets, the teeth ended up getting dark due to cavities. However, the nobility knew how to get around this fact.

Carious teeth became synonymous with “wealth”, as it meant that to have dark teeth due to sugar, you had to have a lot of money to buy sugar.

Soon, there were cases of less affluent people passing soot and other substances to darken their teeth. The lower classes always wanted to imitate the way of life of the elites.

Until the eighteenth century in Europe, sugar would still remain a profitable product and for a long time accessible only by the elites, because in the cases of the lower classes, when they managed to have access to this product, they consumed a sugar of very poor quality, usually called brown sugar, which was seen as of inferior quality, and relegated to the less affluent classes.

In the fifteenth century, the Portuguese already had their sugar cane fields in the south of Portugal, in the Algarve region, and with the beginning of the Era of Discoveries in 1415 with the conquest of the Moorish city of Ceuta in the Maghreb (today Morocco), the Portuguese began their overseas voyages along the West African coast and across the ocean.

Around 1418 the navigators João Gonçalvez Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira discovered the island of Porto Santo, and the following year, Zarco returned in the company of Bartolomeu Perestrelo and discovered the island of Madeira, which came to baptize the archipelago.

Infante D. Henrique (1394-1460), one of the main responsible for Portugal’s maritime expansionist policy, was the one who issued the orders to start the cultivation of sugar cane in Madeira, the Azores, Cape Verde and other locations. D. Henrique saw that sugar was a profitable product, and decided to expand the cane fields in the Portuguese domains.

On the island of Madeira where the first Portuguese mills appeared, in this case in 1452, Diogo Vaz de Teive, squire of Prince Henry the Navigator, built the first mill on the island, in the Captaincy of Funchal.

His mill was powered by water. In 1590, Gaspar Frutuoso, author of Saudades da Terra, pointed out the existence of more than 30 mills in Madeira alone, although it is emphasized that Madeira’s sugar production was in decline due to Brazilian production that had surpassed it.

“In 1440 an arroba was worth 18.30 grams of gold in England, which represents 1:120$000 in today’s purchasing power, or 75$000 a kilo. By 1470, this price had fallen to $45,000, and by 1501 it was worth only $8,500 a kilo. Portuguese production, especially on the island of Madeira, caused the destruction of Mediterranean crops and an imbalance in trade”. (SIMONSEN, 1937, p. 145).

To try to increase the price of the arroba of sugar loaf, in 1496 the Portuguese king, D. Manuel I limited the sugar production of Madeira in 120 thousand arrobas annually, in order to control the availability of the product and soon the prices of sale and purchase. By decreasing the supply of the commodity, prices would increase.

Of these 120 thousand arrobas, according to a note by Furtado [2005], 40 thousand arrobas were destined for Flanders, 16 thousand for Venice, 13 thousand for Genoa, 15 thousand for Chios and 7 thousand for England. These countries were the main consumers of Portuguese sugar.

In 1493, Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) returned to the New World, to the Caribbean Sea, where he had arrived a year earlier, believing that he was somewhere in the Indies, hence he called the natural inhabitants Indians.

Columbus had “discovered” the New World, the West Indies, the Americas on October 12, 1492, on this return voyage he was commissioned by the King of Spain to continue the exploration of other islands, for although the previous year Columbus had reached an island in the Bahamas which he had named San Salvador, on this second voyage, he sighted and visited other islands, but chose to dock on a large island that was named in 1493 Hispaniola (“little Spain”) present island of Santo Domingo, where the countries of the Dominican Republic and Haiti are located, which share the same island. It was in Hispaniola that Columbus founded the town of La Natividad and planted the first sugarcane plantation in the Americas.

“The first serious attempt at colonization took place in the new Iberian possessions in 1502, led by Nicolás de Ovando, and the first American mill seems to have been set up in the Spanish Antilles in 1506.

By 1520, 20 mills had been set up; by 1550, there were about 40 in Espaniola. After 1553, Mexico also began exporting sugar to the metropolis.

Despite this good start, due to the exodus of the populations of the islands to Mexico and Peru, the detour of attention to the mining of precious metals, and the great struggles and revolutions that characterize the early days of the islands of the American Mediterranean, the sugar industry cooled there, which only took on new impetus in the middle of the following century, when there was a great high and considerable increase in demand for the article”. (SIMONSEN, 1937, p. 146).

Sugarcane arrives in Brazil

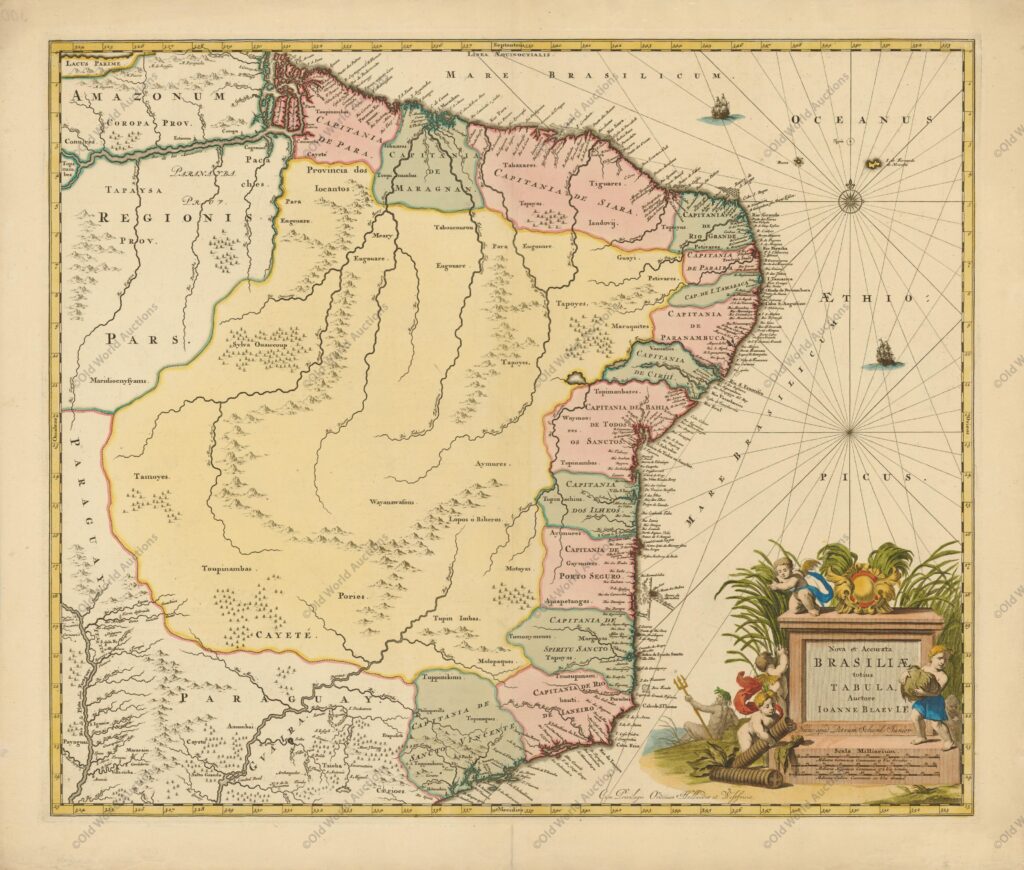

On April 22, 1500, the fleet of twelve ships commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral (1467 / 1468 – 1520) sighted land, which he named Ilha de Vera Cruz.

After making contact with the indigenous people, a few days later the “discovered” land was renamed Terra de Santa Cruz, so that decades later it would be called Brazil.

But anyway from this date of 1500 until 1532, Santa Cruz was not colonized, the Portuguese only occupied themselves in mapping the coast, making contact with the natives, describing the fauna and flora, extracting brazilwood, because gold and silver were not discovered at this time.

In addition, the spice trade in Asia was very lucrative and concentrated the political and economic efforts of the Crown, after all Cabral began his journey with the initial mission of reaching India again, using the route discovered by Vasco da Gama (1460 / 1469 – 1520) in 1498.

In addition to this lucrative trade in oriental spices, Portugal also showed no interest in initially planting sugar cane in the New World something that the Spanish did, as production in Madeira, the Azores, Cape Verde and the Algarves supplied the needs of consumption.

Normally in schools we see that the first seedlings arrived in 1531 in the expedition of Martim Afonso de Sousa, however there are indications that there were previous attempts to grow sugar cane in Brazil, and possibly they would have been successful.

Amaral [1958] points out that in 1516 the House of India, a Portuguese mercantile company that handled business in the Indies, considered sending some sugarcane producers to Santa Cruz (Brazil) in order to study the land and the possibilities of planting sugarcane.

The Brazilian historian Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen (1816-1878), revealed an interesting opinion on the proposal of the House of India:

“We know that, in 1516, he ordered, by a charter, the overseer and officers of the House of India to give axes and enchadas and all other tools to the people who were going to populate Brazil”; and that, by another charter, he ordered the same overseer and officers to “seek and elect a practical and capable man to go to Brazil to start a sugar mill; and that he should be given his allowance, as well as all the copper and iron and other things necessary” for the manufacture of the said mill “. (VARNHAGEN, 1858, p. 95).

In 1526, in the customs records of Lisbon, there was already a tax on sugar produced in Santa Cruz.

Amaral suggests that if there were sugarcane plantations at that time, they should probably have been either in Ilhéus, as Gabriel Soares de Sousa suggested, or in Itamaracá, where one of the most important trading posts in the colony was located.

For Amaral, the sugarcane plantations should have been in Itamaracá, as the trading post of Cristóvão Jacques (ca. 1480 – ca. 1530), a Portuguese nobleman who arrived in Brazil in 1503, was located there.

Jacques returned in 1516 and stayed for three years, leading maritime patrols to fight French pirates, going from the coast of Rio Grande do Norte to the mouth of the Rio da Prata.

It is known that in his travels he fought the French a few times, and took prisoners.

In 1521 he returned and founded a trading post in Itamaracá, which Amaral [1958] thought was the place where the sugar mentioned in the Lisbon customs records of 1526 came from, but it is not certain whether the sugar really came from there, or whether there were cane fields before 1532.

“Sugarcane cultivation in the Northeast – one might add, in Brazil – seems to have begun in the lands of Itamaracá, on the edge of fresh water, as well as salt water; both waters at the same time. And when it was later regularized, with Duarte Coelho, it was to accompany the ‘neighboring lands of the streams'”. (FREYRE, 1967, p. 20).

In 1527, Cristóvão was in Portugal and suggested to King João III to return to Brazil to begin colonization, but the king refused to accept such a request, and three years later sent the expedition of Martim Afonso de Sousa with this purpose.

.

It is important to mention that regular expeditions departed every year from Portugal to Brazil in order to cut Brazilian wood, explore the coast and defend the land, mainly from the French, although the Spanish also passed through at that time.

In 1530 the king of Portugal D. João III appointed the nobleman and military Martim Afonso de Sousa (c. 1490 / 1500 – 1571) for an important mission in the Portuguese colony of Santa Cruz, as it would only officially be called Brazil a few years later, although unofficially some sailors already called the colony Brazil due to the trade in brazilwood.

Martim’s mission was to protect the coast from French ships that were going to smuggle brazilwood, in addition to carrying out new explorations by land and even choosing a place to start a small urban nucleus, this was the antecedent of the hereditary captaincies.

January 31, 1531 they were in front of the Cabo de Santo Agostinho and already in the coast of Pernambuco; finding French ships they hunted them down, taking three, one burned, another sent to the kingdom loaded with Brazil, the third incorporated into the armada, which was on its way to the Rio de la Plata.

In Bahia they were welcomed by Diogo Álvares, the Caramurú, and Pero Lopes found, of the Bahian women, that “they were very beautiful and there was no envy to those of Rua Nova, Lisbon”. (Diário de Navegação, ed. by E. de Castro, Rio, 1927, p. 154). Then in Rio de Janeiro, (p. 174) where they stayed, made landing (14) and exploration, land inwards: “the people of this river are like the Baia de Todos os Santos, if not more gentle people”, says Pero Lopes “. (PEIXOTO, 1944, p. 86).

Martim and his men continued to the Rio de la Plata, but in 1532 they returned north and landed on the island of São Vicente (today on the coast of São Paulo), there he chose the place to found the first village of the colony, Vila de São Vicente, at the time sugar cane seedlings were also planted and a mill called “Engenho dos Erasmos“.

Still in the same year the village of Piratininga was founded with the support of João Ramalho, a Portuguese exiled in that region who ended up becoming the son-in-law of the chief Tibiriça.

The village of Piratininga was located inland, already heading towards the plateau. Years later the village of Santos and the village of Santo Amaro were founded.

“The sugar cane brought there from Madeira (Gabriel Soares says it first came from Cape Verde to the Ilhéus) gave rise to the first sugar mill, which became prosperous, under the name engenho dos “Erasmos”, owned by a firm of rich men from Flanders, Erasmo Schetz, whose overseers Anchieta refers to. In the future town of Santos, next to S. Vicente, Braz Cubas established the first monjolo, or engenhoca, of cereal pillar.

Two years after the foundation of the town of São Vicente, King João III decreed the creation of the Hereditary Captaincies in Brazil, dividing the coast into 15 initial captaincies and giving them to their grantees responsible for colonizing the land and developing agriculture and livestock, as well as continuing to explore those forests in search of riches.

“The grantees would be the lords of their lands; they would have civil and criminal jurisdiction, with jurisdiction up to one hundred thousand kings in the first, with jurisdiction in crime up to natural death for slaves, Indians, peons and free men, for people of higher quality up to ten years of banishment or one hundred cruzados of penalty; in heresy (if the heretic was handed over by the ecclesiastic), treason, sodomy, the sentence would go up to natural death, whatever the quality of the defendant, giving an appeal or aggravation only if the penalty was not capital.

The grantees could found villages, with a term, jurisdiction, insignias, along the coasts and navigable rivers; they would be masters of the adjacent islands up to a distance of ten leagues from the coast; the ombudsmen, the public and judicial notaries would be appointed by the respective grantees, who could freely give lands of sesmarias, except to their own wife or heir son”. (ABREU, 1907, p. 36).

In 1535, the grantee of the Captaincy of Pernambuco, Duarte Coelho Pereira (ca. 1485-1554) founded the first sugar mill of his captaincy, in the vicinity of Vila de Olinda (founded by Duarte in 1534), called Engenho Velho.

See also History of the sugar mills of Pernambuco – Beginning and Ending

For Amaral [1958] the importance of Brazil as a new sugar hub was all too clear, to the point that in 1535 in the town of São Vicente there were already more than three mills, that is, three years after the foundation of the first one.

“Since the charter of King Manuel and afterwards, as noted by João Lúcio de Azevedo, “the privilege granted to the grantee to manufacture and own only mills and water mills denotes that sugar farming was the one to be especially targeted”.

In the same sense, the regiments and laws referring to the colony were made: that of Tomé de Sousa, excluding the mill owner from executions for debts; and of the governors of Pernambuco, ensuring privileges to those who built or rebuilt mills; the half nobility granted to those who became mill owners”. (AMARAL, 1958, p. 328).

“In 1576, Pernambuco exported about 70 thousand arrobas of sugar and in 1583 the figure rose to 200 thousand arrobas. “At the beginning of the 17th century,” says de Carli, “Brazil had 200 sugar mills and produced 25,000 to 35,000 boxes of sugar of 35 arrobas each. This was the golden age of sugar in Brazil”. (AMARAL, 1958, p. 329).

In Europe, from the end of the 16th century to the 18th century, sugar was on the rise. Drinks such as tea and coffee began to spread throughout European countries, drinks brought by the Arabs.

Therefore, as not everyone liked to drink tea or coffee pure, they preferred to add sugar or mix it with milk. In addition, chocolate was beginning to be manufactured in Europe, and it required a lot of sugar to sweeten the bitter taste of cocoa. Remembering that chocolate was a luxury item for a long time, and even tea and coffee only began to become popular at the end of the 17th century in some countries, but in others it was from the 18th.

“After the vulgarization of chocolate, it was coffee, whose use has spread since 1650, one of the products that most contributed to the expansion of sugar, known as it is that the consumption of coffee obliges to that of sugar in weight at least equal to that of that”. (SIMONSEN, 1937, p. 173).

To give us an idea of how valuable sugar became between the 16th and 17th centuries, as it began to decline in the 18th century, I will give two examples of an international factor.

The first concerns the fact that in 1580, with the death of the king of Portugal, D. Henrique I (1512-1580), the throne was left without heirs, because the king was a cardinal and had no children, and his predecessor who was his nephew, D. Sebastião, died young and had no children, so the throne was vacant and some candidates appeared to dispute it, one of them was the king of Spain, Filipe II (1527-1598).

Philip managed to be elected king of Portugal, becoming Philip I of Portugal, becoming the most powerful and wealthy king in Europe and the West. Philip owned the prosperous silver mines of Potosí in Upper Peru (present-day Bolivia) and now he owned the lucrative sugar production of Brazil. For 60 years Portugal and its colonies remained under Spanish rule, and this period is called the Iberian Union (1580-1640).

The second example, occurred in the 17th century, sugar had become such a valuable commodity that it led the Dutch to create the West India Company (1621) to deal with business in the Americas, and in 1624 they attacked the city of Salvador, capital of Brazil in order to take it, although they succeeded, they failed after a year of occupation, however, they did not give up, and returned five years later.

From 1630 to 1654, that is, for 24 years, the Dutch occupied part of Northeast Brazil, controlling the sugar production of Pernambuco, Paraíba, Itamaracá and Rio Grande, the main producers of this much coveted “white gold”.

According to the report of the Dutchman Adriaen van der Dussen, completed in 1639 for the West India Company, Dussen pointed out that Pernambuco, Itamaracá, Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte had at least 166 mills, although today it is known that there are uncertainties in the accuracy of his calculation, however, his report is still one of the best that exist from this period of Brazilian history.

“Brazilian sugar dominated the trade in this product between 1600 and 1700, as Barlaeus already recorded in the work he wrote in 1660, and at a time when it was the most important item in international maritime barter. There were no large-scale transports of cereals, fuels, manufactured and metallurgical goods, and the industrial revolution had not yet emerged”. (SIMONSEN, 1937, p. 179).

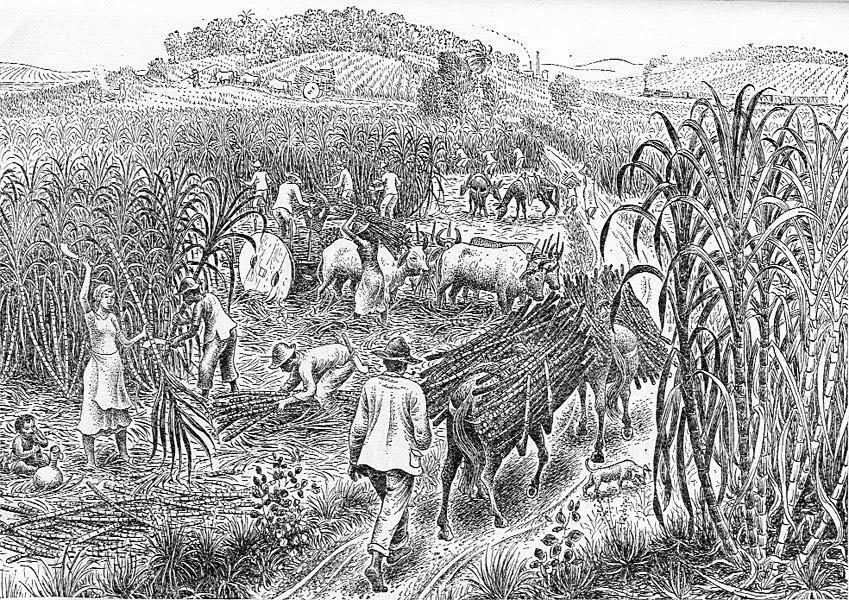

Development of sugarcane cultivation in Colonial Brazil

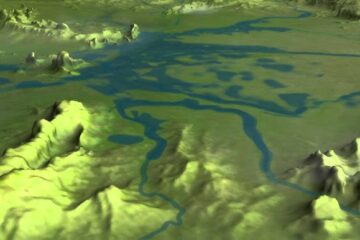

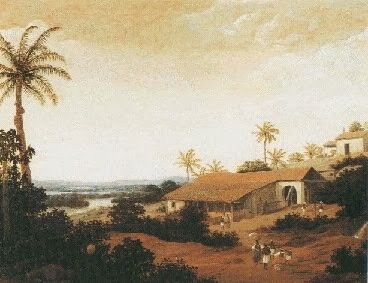

Land, water and forest contributed to the development of sugarcane culture in Brazil.

Gilberto Freyre (1900-1987) and the Jesuit priest José de Anchieta (1534-1597) went so far as to say that one of the main factors contributing to the development of sugarcane cultivation in Brazil was not exactly the tropical climate similar to that of South Asia, but rather the regularity of rainfall and the fertile massapê or massapé soil.

Massapê soil is a dark, sticky soil (because it is rich in clay), rich in humus, something that gives it its fertility.

In geology, massapê, as this type of soil is called in Brazil, is the second most fertile, behind the so-called “purple earth”, although in reality it is reddish in tone, this soil is the result of millions of years of decomposition and sedimentation, mainly of basaltic origin.

Terra roxa and massapê are considered the most fertile soils in Brazil, and both have been exploited; the former mainly for sugar and the latter mainly for coffee.

“Massapê is accommodating. It is a sweet land even today. It does not have that crunch of the sand of the sertões that seems to repel the boot of the European and the foot of the African, the foot of the ox and the case of the horse, the root of the Indian mango tree and the bruise of the sugar cane, with the same disgust as someone who repels an affront or an intrusion.

The sweetness of the lands of massapê contrasts with the gnashing of the terrible anger of the dry sands of the sertões”. (FREYRE, 1967, p. 7).

“The quality of the soil made possible the civilizing advance of sugarcane in several other lands of Brazil. But the stability of its culture in the extreme Northeast and in the Recôncavo is explained by particularly favorable conditions of soil, atmosphere, geographical situation”. (FREYRE, 1967, p. 8).

In addition to the excellent quality of the soil, there was the factor of the tropical climate being suitable for the cultivation of sugarcane, in addition, there was the availability of regular rainfall on the coast, as well as the existence of several rivers and streams that not only provided irrigation, the supply of men and animals, but also the transportation routes for sugarcane, where boats and barges followed the rivers to the sea or near it, where the sugar was taken to the ships that were waiting to take it to Europe.

“In the sugarcane Northeast, water was and is almost everything. Without it, a crop so dependent on rivers, streams and rains would not have prospered from the 16th to the 19th century; so friendly to fat and humid lands and at the same time to the sun.” (FREYRE, 1967, p. 19).

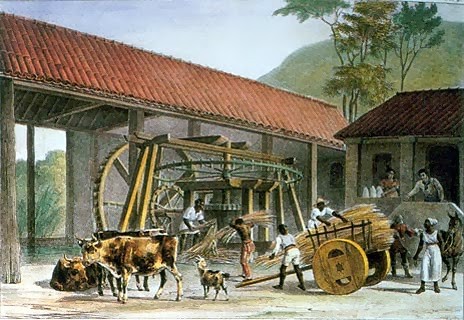

It is also important to mention that in addition to the factors related to water mentioned above, Brazilian mills were powered by water or animal traction.

Although the Portuguese already knew the windmills, something brought by the Moors, centuries earlier to Portugal and Spain; in Brazil, such mills were not applied to sugarcane fields. Therefore, we see mills near rivers, streams or canals built to carry water to move the water wheel.

“They therefore entailed a great deal of transportation of cane, firewood and the goods produced. Given the difficulties of locomotion and the risks of attacks by the savages, the distance from the coast was avoided, and the mills were established preferably on the coastal strip, next to the small rivers, where they used boats for transportation services; however, it soon became necessary to use the ox cart and the appeal to the shooting board “. (SIMONSEN, 1937, p. 149).

“Along the arm of the river that they call Afogados, there are numerous mills from where the Portuguese usually ship their sugar boxes in boats, along the river, or in carts, to Barreta, from there transporting them in chatas to Recife and Olinda”. (NIEUHOF, 1682, p. 24).

Another factor was distance. The Northeast was closer to Africa from where African slaves had come to work in the fields, and at the same time, it was closer to Portugal.

Although there were sugarcane plantations in Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro and São Vicente, these places were much farther from Portugal, and this hindered the sugar trade, in addition, the soil there was less fertile than the dark massapê land on the northeastern coast.

Soon, the sugar production in the south was more focused on the domestic market, although also for the African market, because it was closer to go to Africa than to go to Europe.

However, there were ships that even with the distance, still went to Portugal, carrying sugar.

The availability of wood was also important for the development of the plantations, something ironic, since a large part of the Atlantic Forest was cut down or burned to make room for the sugarcane plantations, but it was from these dense and green forests that the wood for the construction of houses, chapels, mills, water wheels, mills, carts, tools, furniture, boats; besides serving as firewood for the ovens.

“The impoverishment of the soil in so many parts of the Northeast, due to erosion, cannot be attributed to the rivers, to their eagerness to flow to the sea taking the fat from the land, but mainly to monoculture.

By devastating the forests and using the land for a single crop, monoculture allowed the other riches to dissolve in the water, to be lost in the rivers.

This is also linked to the destruction of the forests by fire and the axe, in which monoculture was so excessive. Thus disappeared that vegetation as if astringent, the banks of the rivers, which resisted the waters, rainy weather, not letting them take the marrow of the land: preserving the humus and sap of the soil “. (FREYRE, 1967, p. 22).

“The drama that took place and is still taking place in the Northeast did not come from the introduction of sugar cane, but from the brutal exclusivism in which, out of greed for profit, the Portuguese settler slipped, stimulated by the Crown in its already parasitic phase.

Of this drama, one of the cruelest aspects was the destruction of the forest, leading to the destruction of animal life and it is possible that in changes in climate, temperature and certainly water regime.” (FREYRE, 1967, p. 46).

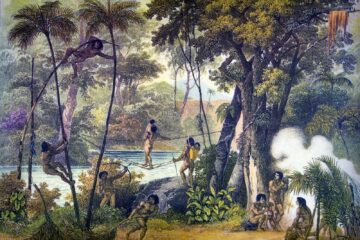

Canavial and Slavery

So far we have seen the trajectory of sugarcane in crossing half the world until it reached Brazil, how this product was in evidence in modern Europe, hence it was so required and profitable; how natural and geographical factors favored the development of sugarcane, driven by a monoculture economic policy (called plantation by the English), where large estates with slave labor were aimed.

However, as we will see later, not all sugarcane plantations were large estates, there were small and medium-sized properties that planted sugarcane and took it to the mills to be crushed. There was a relationship between these small and medium-sized producers and the mill owners, something that is not usually mentioned in schools.

With the beginning of colonization, grantees were granted the right by the monarch to donate sesmarias (land titles) for settlers to settle in the lands of their captaincies.

The donations were usually very large, with plots measuring many leagues. This is understandable: there was plenty of land, and the ambitions of those pioneers who had been recruited at such great expense would clearly not be satisfied with small properties; it was not the position of modest peasants that they aspired to in the new world, but of great lords and landowners. Moreover, and above all because of this, there is a material factor which determines this type of land ownership.

The cultivation of sugar cane was only economically suitable for large plantations.

To clear the land properly (a costly task in this tropical and virgin environment so hostile to man) required the combined efforts of many workers; it was not an enterprise for small isolated owners.

Planting, harvesting and transporting the product to the sugar mills only became profitable when done in large volumes. Under these conditions, the small producer could not subsist”. (PRADO JR, 1981, p. 19).

Prado Jr [1981] and Furtado [2005] pointed out that wage labor in these estates was not a viable economic condition for some factors: .

- Firstly, the Portuguese population was small, and a large part of those who could work in agriculture had to remain in the metropolis, or were on the islands, or were on duty in trade with Africa and Asia;

- Secondly, it would be necessary to hire workers from other countries, but the wages would have to be very good to convince a farmer to leave his land and move with his family across the ocean, to a region considered “wild” by Europeans;

- Thirdly, the large amount of labor needed added to the costs of travel, wages, would lead to the unfeasibility of the project, as building a mill was quite expensive at the time.

- Fourth, the settlers who went to Brazil, went in search of enrichment and glory, so as to return to their countries. Therefore, the final and most viable solution was to appeal to the use of slavery.

In order to work on these estates, the Portuguese initially enslaved the Indians, but these, realizing the true intention of the Portuguese, began to rebel.

The so-called “meek”, ended up accepting to work for the Europeans, but in other tasks; already the more harsh preferred to flee to the woods, returning to their villages, and began to fight the Portuguese. In addition, religious orders began to intervene in the government protesting against the use of Indians in sugarcane plantations, claiming that they should be catechized and used in other tasks.

Indian slavery in Brazil lasted until the 19th century, where hundreds of thousands of Indians were killed. As the Indians began to oppose forced labor in the fields, and in addition, had no experience with that type of work, the solution was to bring slaves from Africa.

“In the first place, as more settlers arrived, and therefore more demands for work, the interest of the Indians in the insignificant objects with which they had previously been paid for their services diminished. They gradually became more demanding, and the profit margin of the business diminished in proportion.

It was even possible to give them weapons, including firearms, which was strictly forbidden, for reasons which are understandable. Moreover, if the Indian, by nature nomadic, had done more or less well with the sporadic and free work of extracting brazilwood, the same was no longer true of the discipline, method and rigours of an organized and sedentary activity such as agriculture.

Gradually it became necessary to force them to work, to keep a close watch on them and to prevent them from running away or abandoning the task they were engaged in. From there to outright slavery was only a step. It had not yet been 30 years since the beginning of the effective occupation of Brazil and the establishment of agriculture, and already the slavery of Indians had become widespread and firmly established everywhere”. (PRADO JR, 1981, p. 21).

Another factor was that the Portuguese had already been using Africans in the cane fields in Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, and even in Madeira and the Azores, notwithstanding, the contact between Portugal and some African nations such as the Kongo, already had some decades of relationship, so it was not difficult for the Portuguese to get slaves in Africa, because slavery was already practiced, and one was already aware of it, although the treatment with the slave was different among the African peoples; slavery imposed by Europeans, became more abusive and aggressive.

However, although there was abundance in getting captives in Africa, the transportation of these men and women was not easy, and made the trip expensive, dangerous, and adding all this, in the end, the price of a slave increased a lot. Depending on age, physical size, appearance and location, the value of slaves varied.

“The process of replacing Indians with blacks continued until the end of the colonial era. In some regions, it will be rapid: Pernambuco, Bahia. In others it was very slow, and even imperceptible in certain poorer areas, such as the Far North (Amazonia), and until the 19th century in São Paulo.

There was a very strong argument against the black slave: his cost. Not so much because of the price paid in Africa, but because of the great mortality on board the ships that transported them.

Poorly fed, accumulated in such a way as to maximize the use of space, enduring long weeks of confinement and the worst hygienic conditions, only a portion of the captives reached their destination. It is estimated that, on average, only 50% arrived alive in Brazil; and of these, many were maimed and useless.

The value of slaves was thus always very high, and only the richest and most flourishing regions could afford them”. (PRADO JR, 1981, p. 23).

Just as the Indians rebelled against slavery, the Africans did the same. The quilombos and mocambos, in addition to some revolts and rebellions, were the response of these men and women to the abusive and nefarious slavery imposed by modern Europeans. However, African slaves became the solution to the demand for labor in the colony.

Thus, African and indigenous slavery became the mainstay of the colonial economy for four centuries. For we have to think that in lands far from the main ports where African slaves arrived, access to them was difficult, so the option was to use Indians as slaves. In the Captaincy of São Vicente (currently the state of São Paulo), indigenous slavery was superior to African.

Types of Sugar Mill

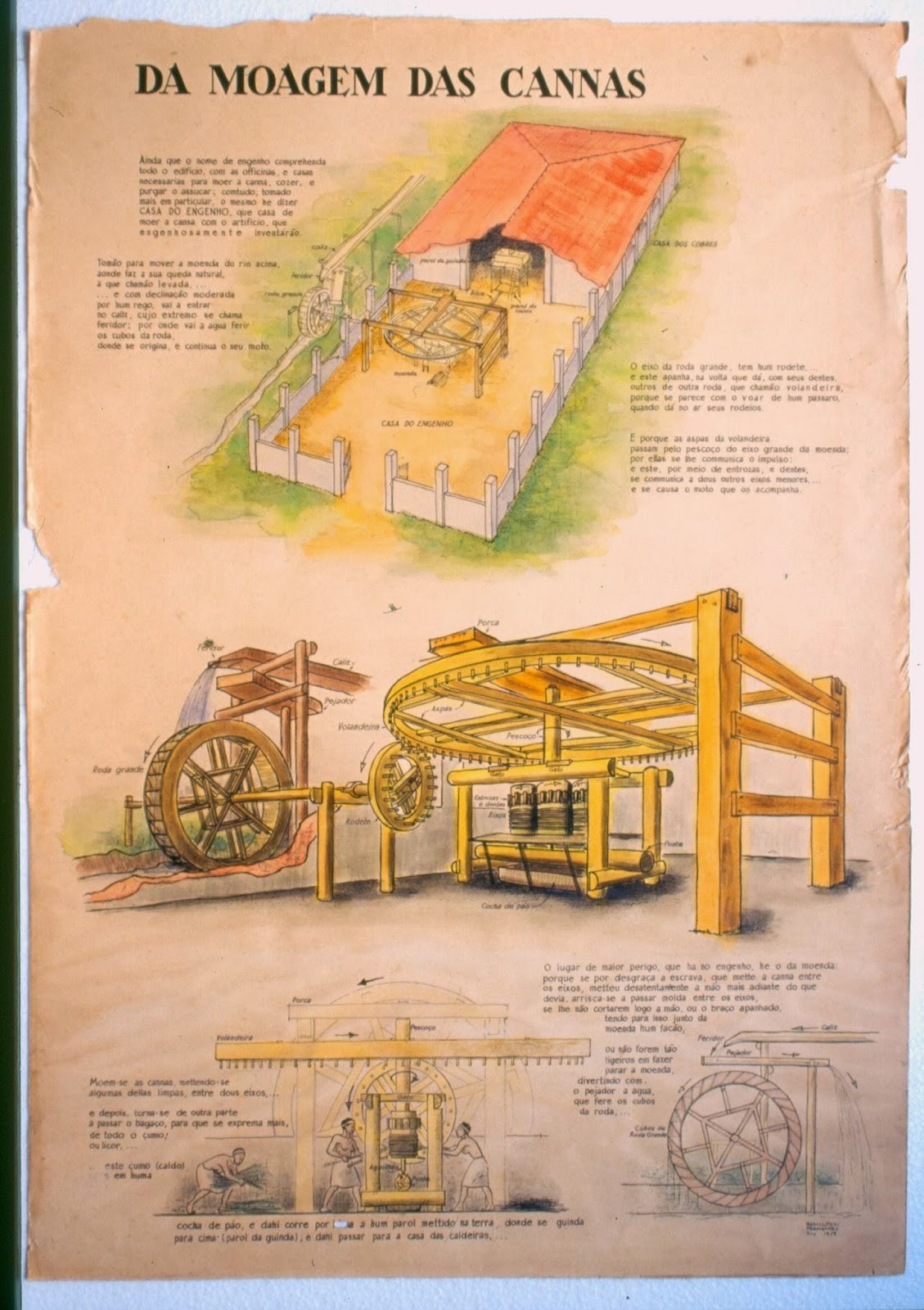

In this case I refer to type when dealing with the issue of the driving force used to turn the gears of the mills, which crush the cane, and from it pours the so-called cane juice, which in turn consists of the raw material for the manufacture of sugar, brandy and rapadura (type of candy), although the cane juice can be consumed pure.

Basically the Portuguese used three types of engenho throughout Brazil’s colonial history, as the third type was only included in Brazil in the 19th century, at the time of the Brazilian Empire.

1. Alçaprensa or alçaprema

Engine powered by human strength. Generally used in the so-called engenhocas (small mills), which manufactured rapadura or brandy for domestic consumption. They could also manufacture small quantities of sugar for home use.

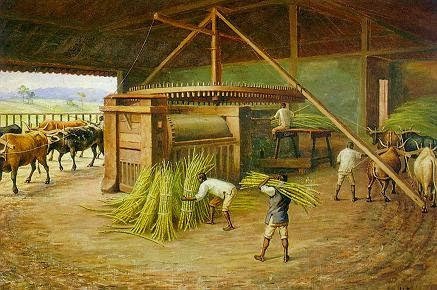

2. Almanjarra, trapiche, molinote, atafona or de oxen

Mill powered by animals, usually oxen, but there were cases where horses were used.

3. Water or royal

Mill powered by water, using a water wheel. They were considered the most efficient for centuries.

Banguê: steam-powered mill. It began to be used from the 19th century onwards. The term was also previously used to refer to mills that produced garapa.

4. Entrosa

Small mill powered by three sticks. Human power was also used.

5. Gangorra

Small hand-held wooden mill with two cylinders. Human power was also used.

6. Dead-fire

Term used to refer to an inoperative mill.

It is important to note that the words, almanjarra, trapiche and banguê have other meanings, hence they are written as: engenho de trapiche, engenho de almanjarra or engenho-banguê, as a way of referring to the use of these words with the structure of sugar mills.

However, depending on the place, one can find other terms to refer to the driving force used in the mills. Here I have used the most common names used in Brazil, Madeira and the Azores.

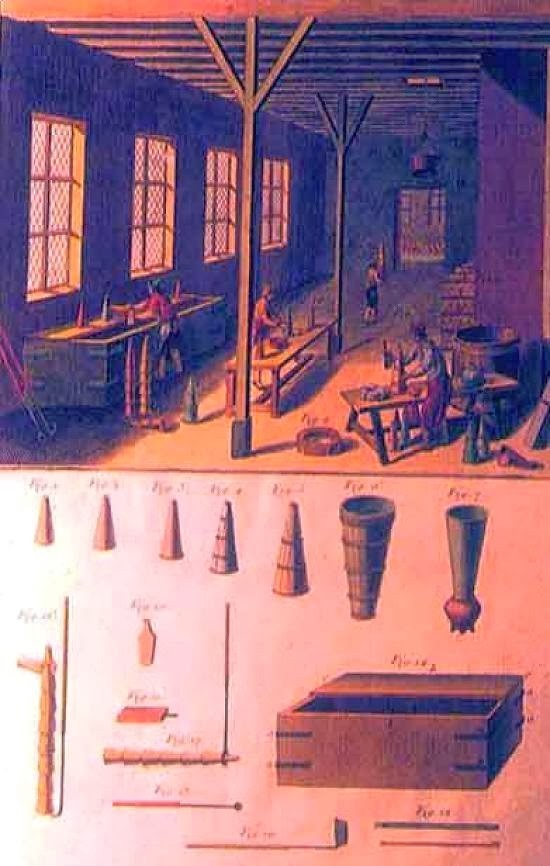

“Whoever called the workshops in which sugar is manufactured, engenhos, really got the name right. For whoever sees them, and considers with reflection that they deserve it, is obliged to confess that they are one of the main achievements and inventions of human ingenuity, which with a small portion of the Divine, always shows itself in its way of working, admirable. Some of the devices are called real, others inferior, commonly called gadgets.

The real ones have earned this nickname, because they have all the parts, of which they are composed, and all the perfect workshops, full of a large number of slaves, with many reeds of their own, and others obliged to the mill; and mainly because they have the royalty of grinding with water, unlike others, who grind with horses and oxen, and are less provided and equipped; or at least with less perfection, and largeness, of the necessary workshops, and with few slaves, to make as they say, the grinding and current mill “. (ANTONIL, 1711, p. 13-14).

In the case of Brazil, the water mills proliferated due to the great availability of rivers and streams, besides also not having initially much cattle, although the use of oxen requires the existence of larger pastures and larger corrals to keep them.

In Brazil it could not be so; the expenses of the colonial installations, in their virgin lands and in a hostile environment, with all their necessary defense, culture, transport and shipping equipment, were so great that in the early days the erection of the so-called small mills was not justified.

Hence the construction of medium-sized mills, producing over three thousand arrobas per year, which were then developed by the construction of facilities with production above ten thousand arrobas”. (AMARAL, 1958, p. 329).

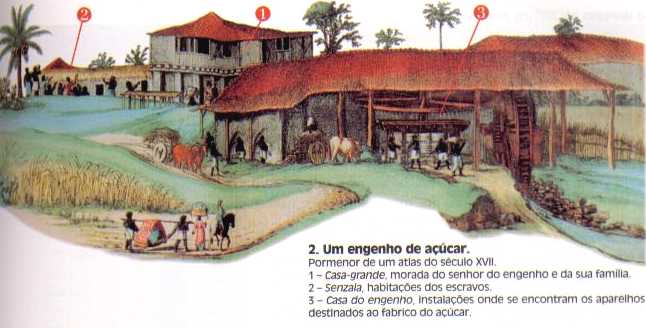

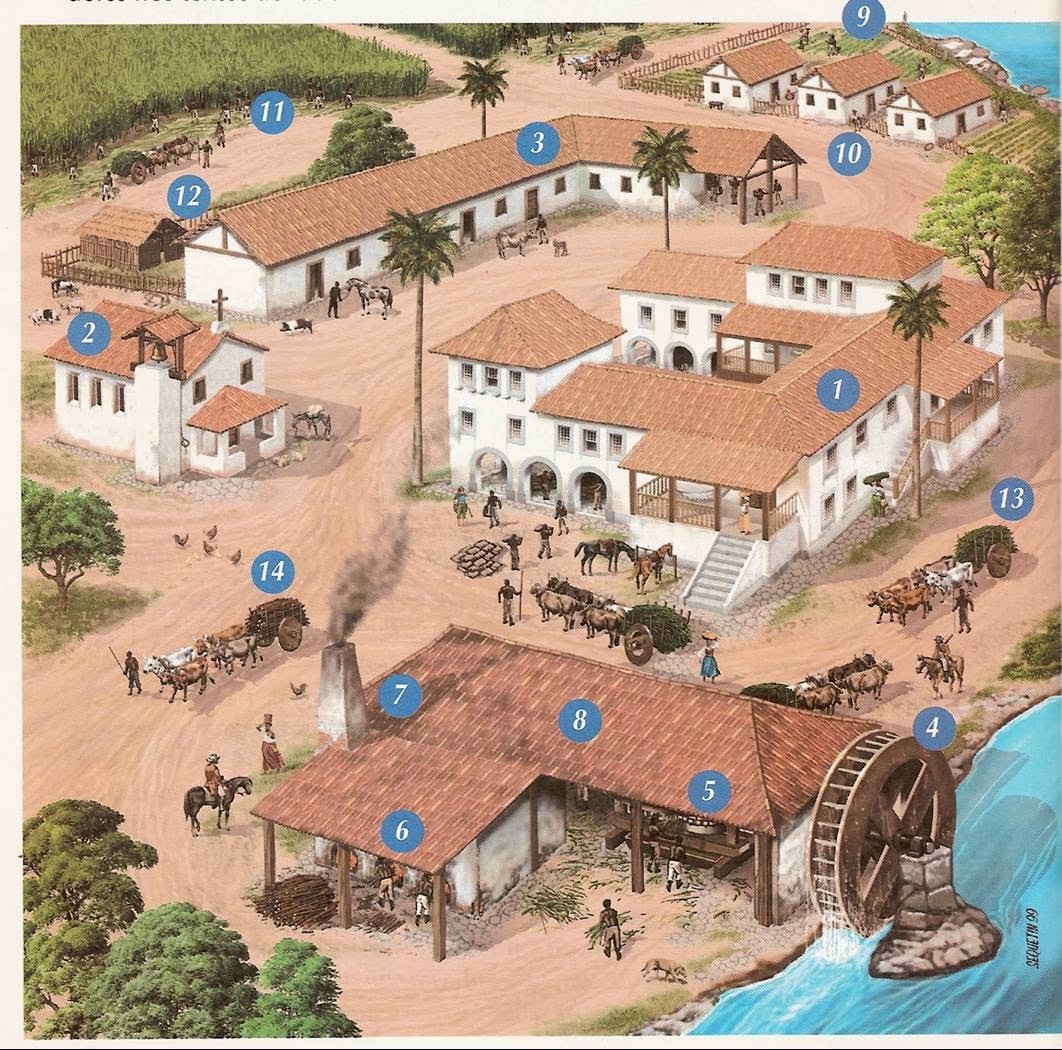

Structure of a Sugar Mill in Colonial Brazil

In the rural nomenclature, the word engenho came to refer both to the so-called Casa de Engenho, the place where sugar cane was ground and sugar, rapadura or aguardente was produced; but it also came to refer to the entire farm itself, to the entire agro-industrial complex involved in the cultivation of sugar cane and the preparation of sugar.

Estrutura de um Engenho de Açúcar no Brasil Colônia

“Its central element is the engenho, that is, the factory itself, where the facilities for handling cane and preparing sugar are gathered. The name “engenho” (sugar mill) was later extended from the factory to the entire property with its land and crops: “engenho” and “sugarcane property” became synonyms”. (PRADO JR, 1981, p. 23).

“The mill represented a real settlement, requiring the use not only of many arms, but also the necessary lands of sugarcane fields, bush, pasture and supplies.

In fact, in addition to the mill house, the dwelling, senzalas and infirmaries, it was necessary to count on about one hundred settlers or slaves, to work about 1,200 tasks of massapê (of 900 square fathoms), in addition to pastures, fences, containers, utensils, iron, copper, oxen and other animals.” (SIMONSEN, 1937). (SIMONSEN, 1937, p. 149).

What would a mill be in the century of discovery? The same thing still described by Saint-Hilaire in the nineteenth century. Fernão Cardim describes it:

Each of them is an incredible machine and factory; some are water mills, others water mills, which grind more and with less expense; others are not water mills, but grind with oxen, and are called trapiches; these have a much greater factory and expense, although they grind less, they grind all the time of the year, which the water mills do not have, because sometimes they lack it.

In each of them there are usually six, eight or more white dwellings and at least 60 slaves, which are required for the ordinary service, but most of them have one hundred and two hundred slaves from Guinea and the land.

The trappings require 60 oxen, which grind every 12 hours in turn; the work usually begins at midnight and ends the next day at three or four hours after midday. Each task is done with a 12-layer firewood barrel and 60 molds of white, brown, soft and high sugar are poured into it. Each form is just over half a bushel, although in Pernambuco large bushels are already used.” (AMARAL, 1958, p. 329).

Gilberto Freyre in his books Casa-grande & Senzala (1933), Nordeste (1937) and Açúcar (1939) had pointed out that the main structures of a engenho (here in the sense of farm) were:

- casa-grande

- senzala,

- engenho

- chapel

- canavial

The casa-grande was the home of the engenho lord and his family, the name “casa grande” was not for nothing, as they really were real mansions, but these mansions only started to become luxurious from the end of the 18th century and throughout the 19th. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the big houses were not so luxurious, and were even made of mud, washed stone, lime, straw or thatched roof. Freyre points out that in the 19th century, we already notice more expensive and more luxurious materials in the construction and decoration of these houses.

“To be the lord of a plantation is a title to which many aspire, because it brings with it being served, obeyed and respected by many. And if it is, as it should be, a man of wealth and government, it is well to be esteemed in Brazil as the lord of a mill, as the titles among the noblemen of the kingdom are proportionately esteemed.

Because there are mills in Bahia, which give the master four thousand loaves of sugar, and others little less, with cane forced to the mill, of whose income the mill gets at least half, as of any other, which is freely ground in it; and in some parts even more than half “. (ANTONIL, 1711, p. 19).

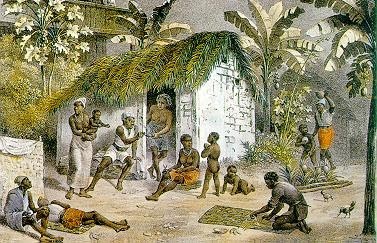

The senzalas were extensive, as they housed 20, 50 or more slaves, as it depended on the fortune of the mill master to be able to buy labor, but in general the large mills had between 50 and 60 slaves.

There was no division of rooms; men, women and children slept in the same place. In front of the senzalas was the so-called tronco or pelourinho, a place used to punish or “educate”, as it was called in the 16th century, the slaves.

The chapel was a religious and governmental necessity, because as Portugal was a Catholic nation, and its population massively Catholic, because the Indians and Africans were converted to Catholicism, it was necessary for Catholic Christians to attend Sunday masses, to go to confession with the priest, to baptize their children, to catechize, to chrismate, to marry, to participate in liturgical days, etc. As the farms were far from the towns and cities, it was necessary to take the word of God to the faithful, hence the large farms had chapels and chaplains.

In addition to being the clerical representatives on these farms, the chaplains were also responsible for educating the children of the plantation owner.

In the case of the boy, when he reached adolescence he would be sent to another school in the village or city, or if necessary, he would go to Portugal to study at universities in Lisbon or Coimbra, however, this practice of sending the males to Portugal began to become more common in the 18th century, before that, we have few mill owners sending their children to Europe, because for them, what their children should learn, they would learn right there, so they could manage the farm.

In addition to the sugarcane fields that were the main plantations of the engenho, there were other small crops, because one does not live only on sugar. We find in the large farms and even in the medium and small ones, the crops or roçados, using a Brazilian term for it.

The “roçados” or “roça” cultivated mainly cassava, from which flour was made (cassava if eaten raw offers the risk of poisoning, hence the need to make flour to purge the poisonous substance).

Because for a long time there were no wheat plantations in the colony, only the rich could import wheat flour to make bread, cakes, pasta, etc., but even the rich who did not like the high prices of wheat flour, had to settle for cassava flour. Manioc flour was the staple food for colonial society, and even to feed the slaves and animals.

These gardens were created to ensure the feeding of slaves, because initially there were no gardens in the mills, so the mill owners depended on having to buy food in the villages, cities or other farms, however, over time, we already noticed these gardens in large properties.

These plantations, which in addition to planting manioc, planted other vegetables such as legumes, beans, rice, corn, potatoes, bananas, oranges, lemons, pineapples, mangoes, jackfruit, potatoes, etc. were tended by slaves or free people.

In addition to the engenho master, his family and the chaplain, there were other free men and women, who performed various jobs, from working in the manufacture of sugar as will be seen later; worked as foremen, supervising the slaves; worked as artisans, blacksmiths, boatmen, fishermen, cowboys, shepherds, potters, etc., took care of the gardens, acted as messengers, doctors-informalists, etc.

On the farms there were chicken coops, corrals, pigsties, stables, workshops, potteries, warehouses, houses for free residents or for slaves who had obtained the right to start a family; in the mills, the corrals were larger to house the oxen and cows used to move the mill, and there was also the need for pasture to feed the cattle, because in the large sugarcane plantations it was problematic to dedicate land for pasture, in addition to having to keep watch so that the cattle would not eat the cane field.

“Apart from this, the engenho was an autonomous economy; for the slaves, cloth was woven right there; the family’s clothes were made in the middle of it; the diet consisted of fish caught on rafts or, otherwise, oysters and shellfish caught on the beaches and in the mangrove swamps, game caught in the bush, birds, goats, pigs for the southern bands, for the northern ones sheep mainly, raised at home – hence the ease of accommodating unexpected guests, and hence the colonial hospitality, so characteristic even today of little frequented places.

Of dairy cows there were corrals, few, because they did not make cheese or butter; little beef was consumed, due to the difficulty of raising rezes in places unsuitable for their propagation, due to the inconveniences for the crop resulting from their propagation, which reduced these cattle to what was strictly necessary for agricultural service “. (BRANDÃO, 1956, p. 6).

“There were mills powered by water and by oxen; served by carts or boats; situated by the sea or further away, but not too far away, because the difficulties of communications only allowed arcs of limited radius; there were enough to produce more than ten thousand barrels of sugar and incapable of giving a third of that sum. Let us imagine a schematic mill for comparison – from the schematic the existing mills differed more or less, as is natural.

It had to have large cane fields, abundant and nearby firewood, a large slave population, a capable herd, various apparatus, mills, coils, moulds, purging houses, stills; it had to have trained staff, since the raw material went through various processes before being delivered for consumption; hence a very imperfect division of labor, especially a certain division of production.

The product was sent directly overseas; payment came from overseas in cash or in objects given in exchange, and there were not many of them: fine farms, drinks, wheat flour, in short, luxury objects.

For luxury they could buy supplies from the less well-off farmers and this was usual in Pernambuco, so much so that among the grievances of the Pernambucans against the Dutch was that they were forced to plant a certain number of cassava cups”. (BRANDÃO, 1956, p. 6).

A fact to mention before proceeding to the next part of this work, it is important to note that the mill owners could give part of their land to tenants, as well as received the production of smaller farmers, to be ground in their mill.

“Although the owner usually exploits his land directly (as understood above), there are frequent cases in which he cedes parts of it to farmers who cultivate and produce sugarcane on their own account, but are obliged to mill their production in the owner’s mill.

These are known as “fazendas obrigadas”, where the farmer receives half of the sugar extracted from his cane, and also pays a certain percentage of the rent for the land he uses, which varies according to the time and place, ranging from 5 to 20%. There are also free farmers who own the land they occupy and mill their cane in the mill they want; they receive the full share of the land.

Although these farmers are socially below the mill owners, they are not small producers in the category of peasants. They are slave masters, and their crops, whether on their own land or leased, form large units like the mills”. (PRADO JR, 1981, p. 23).

As Caio Prado Júnior had pointed out, the engenho lords cooperated with some farmers who exploited part of their land for them, or in the case of their own owners, they provided cane to be milled in their engenhos.

This practice is old, since before the mid-17th century, the Dutchman Adriaen van der Dussen mentions in his report that many of the mills had businesses with tenants, these free farmers. Therefore, in his report he uses the terms “farm party” and “task”.

The first term refers to the lord of the mill, while the second term refers to the farmers who supply cane to be crushed in the mill. In exchange for giving up their inns to mill the cane of others, the engenho lord kept a percentage of these “tasks”. However, the farmers were responsible for transporting the cane to the mill and fetching the sugar.

National Sugar and Alcohol Museum

A significant part of the history of sugarcane processing, until today one of the pillars of Brazilian agribusiness, can be seen and learned in Pontal, in the Ribeirão Preto region. The first stage of the National Museum of Sugar and Alcohol, maintained by the Engenho Central Institute of the Biagi family, has been open to the public since December and is already attracting visitors.

The collection is exhibited at Engenho Central, built in 1906, a year before the emancipation of the municipality.

The museum’s collection includes machinery produced in Europe between 1876 and 1888, such as seeding machines, supply pumps, barrels for benefiting and purifying sugar, containers for transporting brandy, identification stamps for sugar bags and the clock that was in the mill’s tower.

The Central Mill belonged to farmer Francisco Schmidt, the King of Coffee, who produced sugar for export to the German company Theodor Wille, based in Hamburg. Before belonging to the mill, the machines belonged to another farmer, Henrique Dumont, father of the aviator Santos Dumont.The Biagi family bought the farm in the 1960s and the mill continued producing until 1974.

When Maurílio Biagi died, his son, Luiz Biagi, decided to keep the mill and create the Institute to give shape to the museum. The installation had the support of the laws of incentive to culture.

The museum is open from Tuesday to Sunday, from 10 am to 4 pm, with free admission.[/box]

“Each task represents what a mill can grind in a day and a night, that is, in an oxen mill between 25 and 35 cars of cane and in a water mill between 40 and 50 cars. The farmer is obliged to plant cane, with the help or not of the mill master, depending on the terms of the contract.

The cane, once planted, lasts as long as human life and does not need to be replanted except here and there, where a ratoon dies, unless it is burned during the summer or a river runs dry. […]. Besides, the farmer has to take care of his cane field and clean it 2, 3, 4 times a year, because if he lets weeds grow next to the cane, the whole plantation will die”. (DUSSEN, 1947, p. 93).

“The sugar produced is divided with the mill master, according to the case: the farmers who have their own land and parties and who can grind their cane where it suits them best, the division of sugar is usually made half and half; those who plant on land belonging to the lord of the mill, divide some in the proportion of 1/3 for the farmer and 2/3 for the lord of the mill, when the land is fertile and close to the mill and for this reason the farmer has little expense; for the majority the division is made on the basis of 2/5 for the farmer and 3/5 for the lord of the mill”. (DUSSEN, 1947, p. 93).

The fact that not all these farmers owned mills was because such inns were expensive. Simonsen [1937] had pointed out that a mill would cost between 10 and 15 thousand contos de réis at the time, but Amaral [1958] disagreed with him, and pointed out that the mills would cost from 30 thousand contos de réis.

Other historians suggest that the mills cost in the range of 35,000 contos réis, just the structure, not counting the labor, because if you add that, the value would rise to at least 50,000 contos réis, just to acquire the dozens of slaves for the work.

This is an interesting fact, since most of the mills came from private capital, because only in a few cases did the State provide funds to build mills in Brazil, so it is said that it was a private endeavor.

Throughout Brazilian colonial history, we will see mills built with Spanish, Genoese, Venetian, Dutch, Flemish, Belgian, German, French, English, etc. capital. We will also notice Catholic, Protestant and Jewish mill owners. On the other hand, the plantation owners had some privileges, such as exemption from the collection of some taxes, as well as some autonomy in the control of their lands and people.

Sugar Manufacture

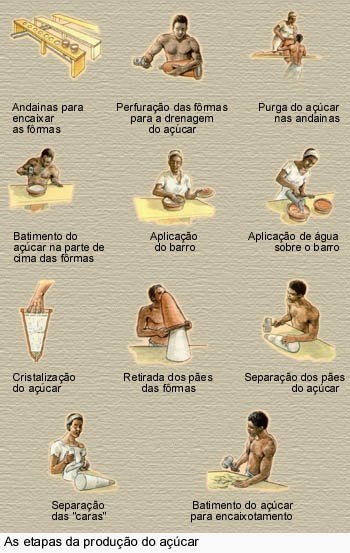

We usually study the macro context of sugar production, but the stages of sugar manufacture are left out. Therefore, in this topic, I dedicated myself to reporting how sugar was manufactured, as well as showing the sections of the sugar mill or mill house.

An interesting fact is that Antonil [1711] who reported on sugar production in the 18th century, tells us that many of the workers in the sugar mill were women as will be seen below, one of the reasons is because women would have more attention and men would have the heaviest work in the cane field and in transportation.

Although it is necessary to mention that this was not something homogeneous, since Antonil spoke from the beginning of the 18th century, but the essential thing to know is that it was the slaves who did the bulk of this work, although there were free workers involved in sugar production.

Celso Furtado [2005] has pointed out that one of the reasons for Portugal’s success in developing the sugar agribusiness was the investment in the development of equipment and techniques in sugar manufacture.

He says that in the 14th and 15th century, sugar manufacture was known throughout the Mediterranean, but in this case, the Genoese and Venetians were the main connoisseurs of these techniques and in the production of equipment, so they had a certain monopoly on the techniques of sugar manufacture.

It is also interesting to note that in the 15th to 17th century the Dutch, Flemish and Belgians specialized in refining sugar, as the mills did not do this. The elites did not want to consume a dense, dark and hard sugar; they wanted a white, fine and crystalline sugar, so it needed to be refined.

“From the mid-16th century onwards, Portuguese sugar production became more and more a joint venture with the Flemish, initially represented by the Antwerp interests and then by those of Amsterdam. The Flemish collected the product in Lisbon, refined it and distributed it throughout Europe, particularly the Baltic, France and England.

The contribution of the Flemish – particularly the Dutch – to the great expansion of the sugar market in the second half of the 16th century is a fundamental factor in the success of the colonization of Brazil. Specialized in intra-European trade, much of which they financed, the Dutch were at that time the only people who had sufficient commercial organization to create a large market for a practically new product, such as sugar”. (FURTADO, 2005, p. 20).

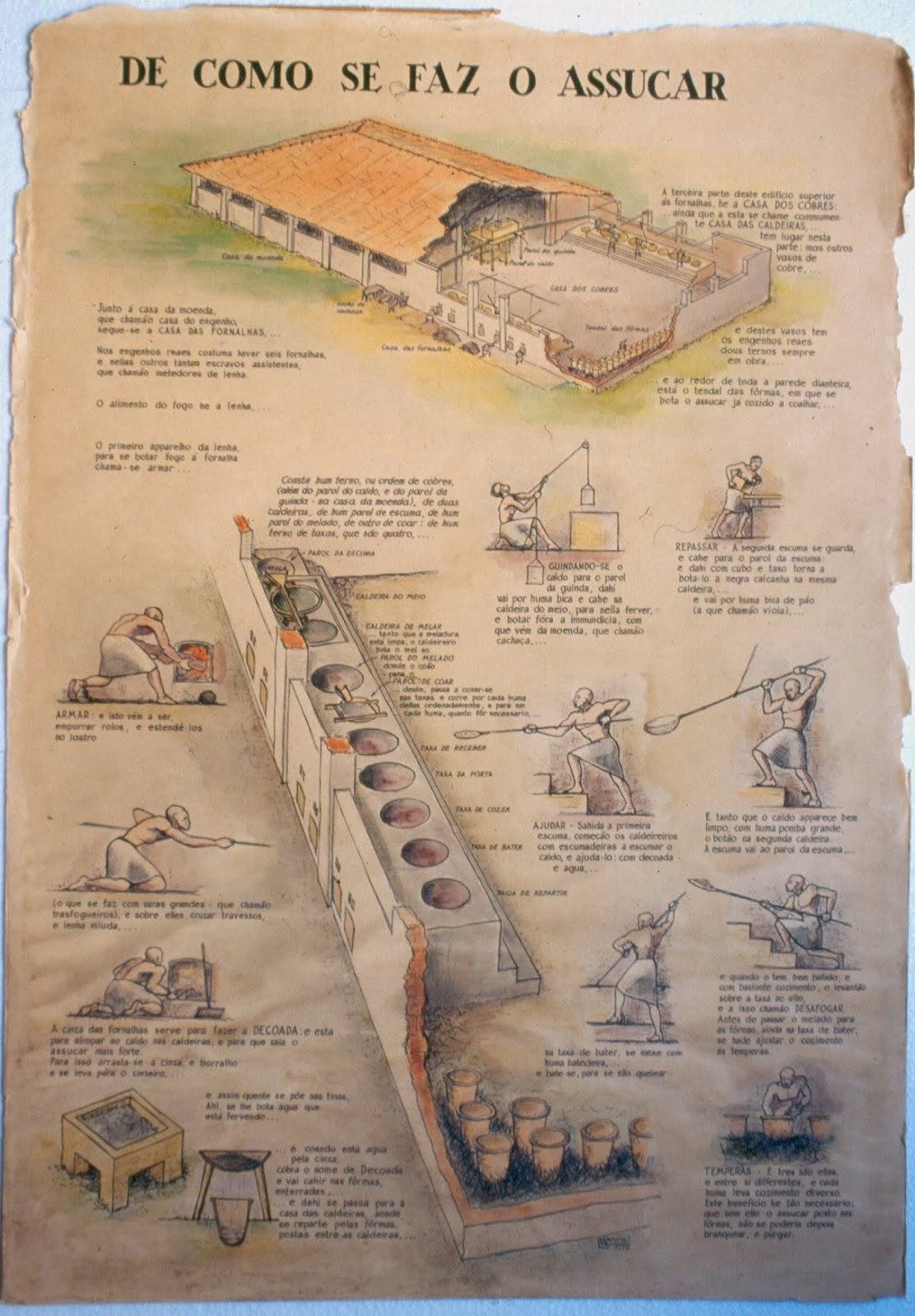

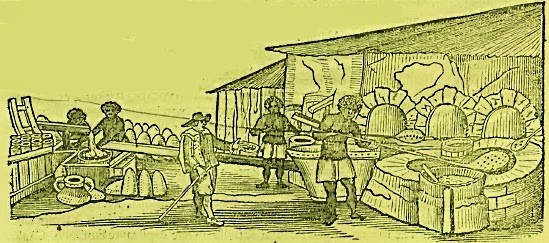

The sugar mill was basically divided into three parts: the mill house, the boiler house and the purging house. Each of these stages represented the phases of sugar manufacture. In the case of the manufacture of cachaça and rapadura there are differences after the second stage, something I will return to briefly below.

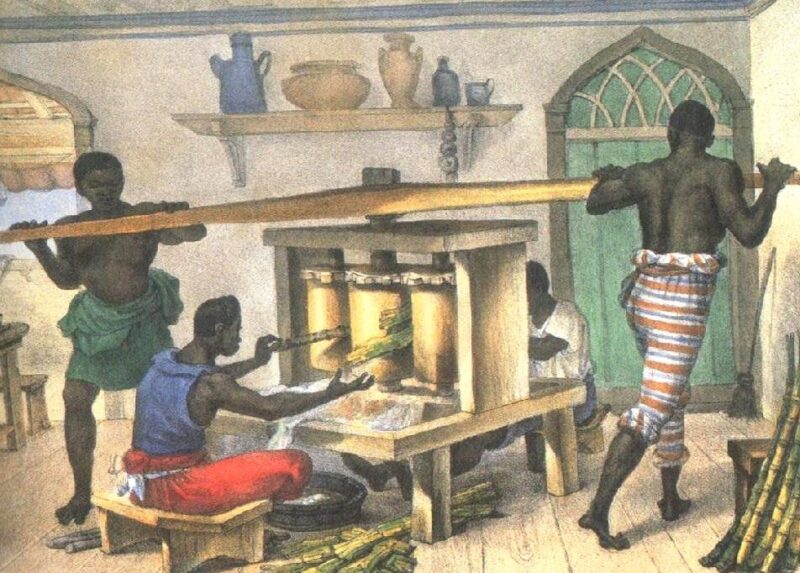

1. Mill house

In this enclosure was the mill, a machine made of wood, which had presses that when moved by a gear mechanism moved by human, animal or hydraulic force, crushed the cane in order to squeeze it with force, thus forcing the juice to come out. This juice was collected in pots and taken to the next stage. Antonil [1711] considers the mill house the most dangerous stage because there was a risk of a slave getting his hand caught and being pulled by the arm by the press, thus being crushed, and may lose his arm or even die.

The danger was doubled by the fact that the mill worked day and night, as already mentioned, so the slaves tired from the hard day could fall asleep, hence the need to always keep several people in the enclosure to avoid such tragedies.

“The most dangerous place in the mill is the mill, because if by misfortune the slave who puts the cane between the shafts, either because of sleep, or because she is tired, or because of any other carelessness, carelessly puts her hand further forward than she should, she risks being ground between the shafts, if they do not immediately cut off the caught hand or arm, having a machete near the mill, or are not so quick to stop the mill by diverting the water that hurts the wheel’s hubs, so that they can quickly give the sufferer a remedy.

And this danger is even greater at night, when it is ground as well as during the day, since those who put the cane in their equipment take turns, especially if those who are in this occupation are boorish, or accustomed to getting rubbery. (ANTONIL, 1711, p. 54).

As has been pointed out, the most efficient mills were those powered by water wheels, although they were the most expensive. In the case of trapiche mills, several oxen were used to move the trapiche that turned the mill.

Depending on the mill, eight, ten or twelve oxen could be used at a time for each work cycle; Dussen [1947] and Amaral [1958] point out that sugarcane milling sometimes took the whole day, going into the night and dawn, as a way of saving time.

“There are at least seven or eight female slaves needed for the mill, namely: three to bring in cane, one to put it in, one to pass the bagasse, one to fix and light the lamps, of which there are five in the mill, and to clean the trough of the broth (which they call cocheira or calumbá) and the stingers of the mill and refresh them with water so that they do not burn, making use of the water parol, which is under the rodete, taken from what falls into the stingers, as well as to wash the cane that is bundled; and another, finally, to throw the bagasse away, either in the river or in the bagaceira, to be burned in due course.

And if it is necessary to put it in a more distant part, not only one slave will suffice, but there will have to be another one to help her, because otherwise it would not flow in time and the mill would be embarrassed”. (ANTONIL, 1711, p. 54-55).

It is important to note that depending on the era, the shape of the mills and their size varied. Therefore, we cannot speak of a homogeneous machine, since they were first made by hand, although they followed certain specifications in the proportions.

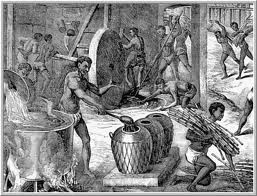

2. Boiler house

This was probably the most dangerous place to work, due to the risks of getting a burn or starting a fire, although Antonil disagrees with this opinion as already presented here.

Gilberto Freyre went so far as to say that in this part of the mill, slaves worked under close observation and could even be chained, as they might try to sabotage production, spill the pots or start a fire.

The boiler house or furnace house has been compared to a “small volcano” in Antonil’s words, but it was a very hot and stuffy place. Some scholars prefer to separate the boiler house from the furnace house because they point out that they were different places, but this depends on which period they are referring to.

In this wing of the engenho were the copper boilers used to boil the broth. Dussen [1947] who wrote in the 17th century, mentions that the mills had 4, 5 or 6 large pots, and 3 to 4 smaller pots.

It was in the large pans that the broth was boiled, and in the smaller pans it was left to cool before proceeding to the next stage. These pans were imported from the Metropolis, as there were no blacksmiths capable of producing such equipment in the colony.

In the boiler house there were several pots as already said, we passed to know them, because they made up step by step in the boiling of the sugar cane juice:

- Clarifying boiler: in the first mills the juice was mixed with lime to help filter out impurities before boiling;

- Caldo boiler: pot where the broth from the mill house was received;

- Middle boiler: pot where boiling began and the first and second foams were removed, which contained impurities such as pieces of leaves, stalks, cane bagasse, etc.

- Molasses boiler: boiling continued and the third foam was removed and taken to the escuma parol. This is also where the garapa was made;

- Parol de melar: after being boiled and having the foams removed, the broth was put here to be strained;

- Cooking pot: receives the broth to be strained. The term temperar is also used at this stage;

- Tacha de receber: after being strained, the broth was stirred, skimmed, boiled and decoated, where water with ashes was added to help filter the existing impurities;

- Gateway Strainer: after the broth has had its foams removed, has been strained and has been decoated, the broth continues to be boiled;

- Cooking pot: the broth continues to be boiled and here it reaches its “point”. This is the last stage of boiling, as from here the so-called molasses will be put in to start the resting and cooling stage;

- Baking stage: the broth continues to be boiled and here it reaches its “point”.

- Whipping bowl: the molasses is beaten with a mixer to reach the crystallization point, becoming more consistent and massive;

- Splitting bowl: After being beaten, the molasses was de-augered, a term used to refer to the act of transferring the molasses from the previous rate to this one, where it would be taken to cooler where it would rest and cool;

- Scum pole: place where the foam of the three foams was deposited to be reused.

Here I have exposed the main steps, but depending on the time, we will notice new steps and pots used in the filtration of the broth, because the process has received new techniques throughout history.

In the boiler house worked some free men called boilermakers, who were responsible for checking the “sugar point”, i.e. the exact boiling temperature.

Antonil [1711] mentions that in this section of the sugar factory most of the workers were men, but there was a slave woman called “calcanha” who was responsible for cleaning the room, lighting the lamps, collecting the second and third foam removed and putting it back in a parol (a type of vessel), as this foam had other uses.

In addition to the pots, parols and boilers other tools and containers used at this stage were:

- Beater: similar to the skimmer, but without the holes. It was used to beat the molasses after it had finished boiling.

- Caneca: container used to pass the broth from one pot to another.

- Cinzeiro: square tank where hot water was mixed with ashes to be used in the decoada, in the rate of receiving.

- Spoon: a large spoon with holes, used to stir molasses after boiling.

- Concha: a long-handled iron ladle, used for tasting the broth.

- Skimmer: a type of spoon with several holes, used to extract the foam.

- Fôrma: clay pot where the molasses was placed to start the purging.

- Passadeira: large spoon used to transfer the boiling broth to the next pot.

- Picadeira: iron spear used to remove the remains of molasses that stuck to the pots, parols and boilers.

- Pomba or reminhol: large spoon used to remove molasses from the last rate. It was also used to add water to the decoada.

- Resfriadeira: tank where the molasses rested and cooled down to be deposited in the molds.

Such equipment and containers were commonly used in the production of sugar, however, when we reach the nineteenth century we already find other utensils and machines such as centrifuges, filterers, foamers, evaporators, etc. used in this process, reflecting the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth century.

After boiling, the juice, which was initially light green or yellowish in color, turns into what is called cane honey, sugarcane honey, boreal honey or molasses. A brownish substance rich in sucrose, carbohydrates, iron, etc.

Molasses is not only used to make sugar but also to make cachaça, rapadura, rum, broths, etc.

The clay pots, also called formwork, sugar loaf and honey bell, were conical or pyramidal containers with a hole at the tip, where the remaining molasses came out through this hole and was deposited in the castile jar, a basin that collected this molasses to be reused.

“The forms of sugar are clay vessels burned in the furnace of the tiles, and have some resemblance to the bells, tall three and a half palms, and proportionally wide, with greater circumference at the mouth, and tighter at the end, where they are pierced, to wash, and purge the sugar through this hole” (ANTONIL, 1711, p. 75).

“In the space of 24 hours they make 20 to 30 moulds in an oxen mill, 40, 50 or 60 in a water mill and 40, 50, 60 or 70 and more moulds if the mill is capable of crushing a lot of cane and if it is rich in sugar, which depends, as has already been said, on the time and care taken in cultivation.

The mould holds one arroba of sugar if it is more or less good, if it is inferior, less. The best sugar weighs more and a form can hold 40 or more pounds up to 50 and 60”. (DUSSEN, 1947, p. 94).

The value of an arroba at the time that Dussen refers to, would currently be worth something approximate in 14.688 kg, which is equivalent to approximately 25 pounds. Thus, a clay pot weighing 2 arrobas, or 50 pounds, would be equivalent to almost 30 kg of sugar.

3. Purging house

Antonil, writing from the 18th century, tells us that the purgar house (purgar means to remove impurities) was usually separate from the sugar mill, and sometimes it was the largest enclosure, because it was there that the sugar was stored to be purged as will be seen below.

He tells us that in Bahia and Sergipe there were large purging houses made of stone, lime and maçaranduba wood. These houses would have an area of more than 200 square meters, real sheds with several windows to allow good air circulation and light to enter, which would help the sun’s heat to dry the sugar more quickly.

In this large space there were rows of scaffolding where the sugar loaves were deposited. This account is interesting, because unlike Dussen and Barléu who refer to Pernambuco, here we have an example from Bahia.

“In the purging house there are shelves where the moulds fit and rest. On each shelf there are 10 to 12 moulds, 8 to 10 shelves next to each other, under each of which are the receptacles for the honey.

This set is called a scaffold. Thus, each scaffold holds about 100 formworks and in a purging house there are 20, 25 and 30 scaffolds, allowing the deposit of 2,000 to 3,000 formworks”. (DUSSEN, 1947, p. 94).

As previously mentioned, depending on the size of the mill and the engine power used to move the mill, sugar production varied. The example given by Dussen comes from a mill in Pernambuco that he visited in the 1630s, a period when the Dutch controlled the region.

These clay forms had a conical or pyramidal shape to facilitate the exit of the remaining molasses that remained inside the container, as this molasses gives a dark color to the sugar, something that is known as raw sugar, more commonly called brown sugar or brown sugar.

Brown sugar has a shade between caramel, light brown and dark yellow, in addition to having a different taste than white sugar.

Inside the molds, Dussen says that the sugar was left to rest for six to eight days, being beaten with a small hammer in order to compress it more and more, in order to squeeze out the rest of the molasses so that it would come out through the hole at the bottom. Antonil [1711] mentions a period of 3 to 15 days to wait for the sugar to purge.

Antonil also mentions that sugar that hardened but did not become brittle was called “closed face”, while sugar that became brittle was called “broken face”, so more attention should be paid to jars of brittle sugar, as this meant that they had not dried properly.

“The hole in these jars, covered at first, keeps the sugar curdled and moist; when opened, it lets the honey pass through to purge the sugar. Then the face of the mould is covered with clay, because it is believed that by repeating this operation several times, the impurities are more completely expelled and the sugar whitens more”. (BARLÉU, 1940, p. 95).

In addition to this mechanical technique of “compressing” the sugar, a thin layer of clay or mud was poured, which slowly mixed with the sugar and in turn the clay absorbed the molasses. This stage was carried out in the purging counter and in the cocho, where the tendal was located, a space used for laying the forms.

“In front of the door of the Purging House there is a porch on six pillars, eighty-two palms long and twenty-four wide, under which is the Masticating Counter; and on another side there is the Trough for kneading the clay, which is put in the Forms, to purge the Sugar; and further on the Counter for drying it, eighty palms long and fifty-six wide, supported by twenty-five brick pillars”. (ANTONIL, 1711, p. 78).

Antonil tells us that four women worked in the purging house, responsible for preparing the clay molds for sugar, as well as washing them.

“The four purging slaves first dig the already dry sugar with iron diggers in the middle of the form’s face (which is the upper part), and then they equalize and trim it very well with mallets; then they put the first clay on it, taking it with a reminhol from the pots, which came full of it from their trough, being already kneaded in their account, and with the palm of their hand they spread it over the entire face of the form, two fingers high.

On the second or third day they put half a reminhol or a gourd and a half of water on the clay, and so that it does not fall into the clay from a blow, and falling make holes in the sugar, they receive the water on their left hand, close to the clay, which they put with their right hand equally over the entire surface, and then with the palm of their right hand they lightly stir the clay, so that their fingers do not reach the sugar face.” (ANTONIL, 1711, p. 83-84).

Dussen mentions that depending on the case, two to three layers of clay were applied to make the sugar purer and whiter.

“Free of its honey, the sugar is brought out of the purging house, removed from the moulds and dried in the sun on stretched cloths, then the sugar that is still mixed with the honey is removed. This is what the Portuguese call ‘mascavar’, which means that they remove the gray mask from the sugar and hence they also call the grayish sugar ‘mascavado’ “(DUSSEN, 1947, p. 95).

“At the chewing counter there are two of the most experienced black women, whom they call mothers of the counter, and with others they chew it and separate the inferior from the best, some blacks who bring and venture the forms, and take the sugar loaves from them, and the kneader of the purging clay, which is also another black man.” (ANTONIL, 1711, p. 79).