Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

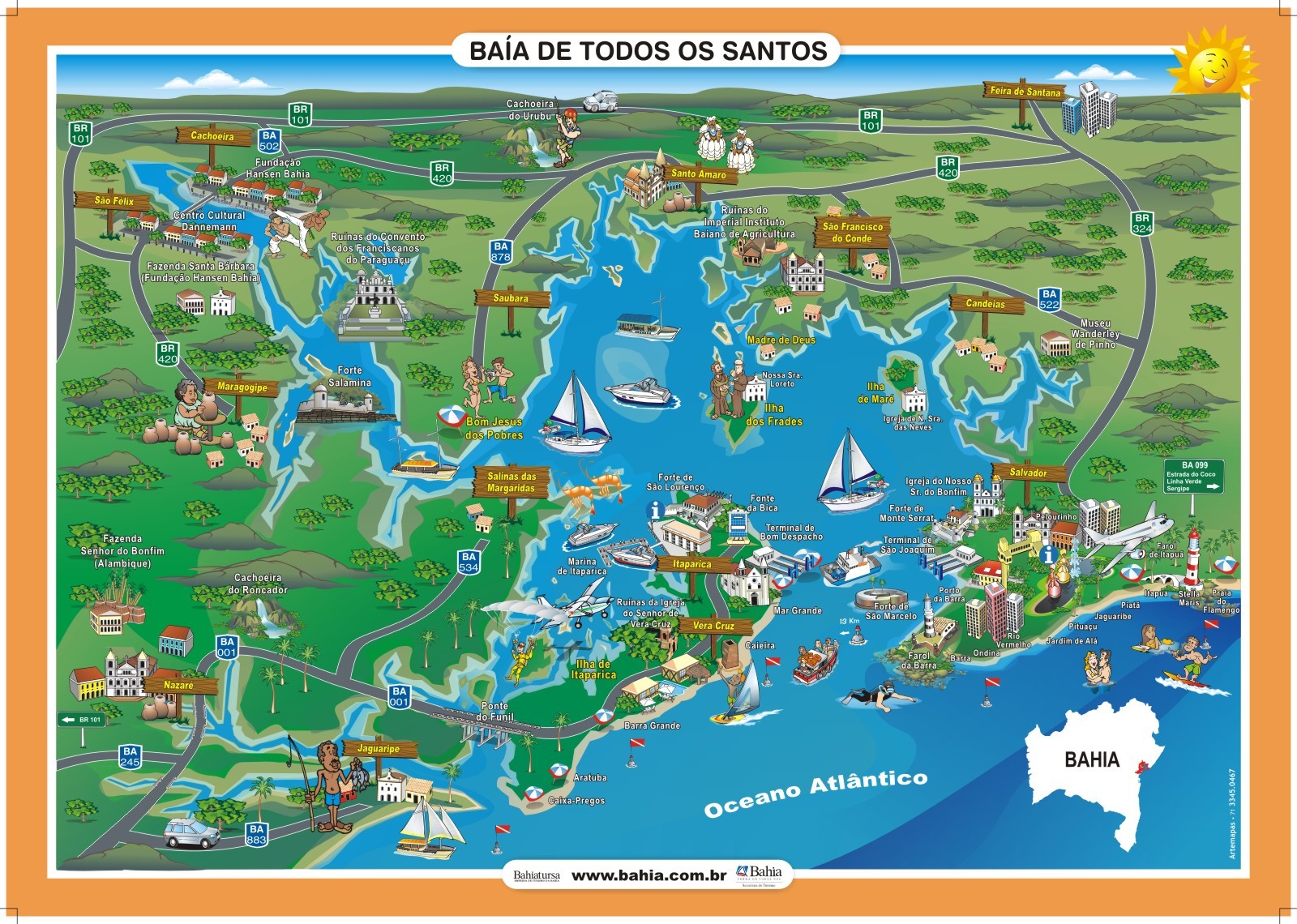

The Bay of All Saints or Baía de Todos os Santos and its recesses constitute an immense amphitheater, where nature, history and culture are molded to form a beautiful setting for nautical tourism and ecotourism activities.

This great scenery is composed of a vast expanse of calm waters, from which 56 islands emerge, among which, Itaparica, the largest of them, Maré, Frades, Madre de Deus, Cajaíba, Matarandiba, Bimbarras and the lands of the thirteen municipalities that border the bay.

There are beaches, forests, trails, rivers, waterfalls, rapids, mangroves, ecological reserves, ruins of sugar mills, old churches and old convents, testimonies of the opulence of the wealth of the cane fields that sprouted from the lands of the massapé.

View the map of Baía de Todos os Santos

Dominating the landscape is the city of Salvador Baia de Todos os Santos, which for more than two centuries was the capital of Brazil and the most important city in the Americas.

City of art, with its baroque excesses, colonial architecture of Salvador would be reflected in the towns and cities that were born from the mills of the Recôncavo Baiano, in which one can recognize the urbanistic ideology of Renaissance Portugal.

Video about the Bay of All Saints – Baía de Todos os Santos

Turismo e História da Baía de Todos os Santos

Alongside these strong marks of colonization, a singular miscegenation between European, African and indigenous cultures has made possible the emergence of a rich folklore, an unparalleled culinary and artistic manifestations that combine, in the right measure, the influences of the three races.

To ensure the protection of its islands, ordering socio-economic activities in the region, and preserving sites of great ecological significance, the Baía de Todos os Santos Environmental Protection Area was created in June 1999.

HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL ASPECTS OF THE BAÍA DE TODOS OS SANTOS

A legend of the Indians recorded by the chroniclers of the early days of the settlement of Brazil narrated that, at the beginning of the world, a great bird with very white feathers departed from very far away and, flying nights and days without stopping, reached the coast of an immense land where, exhausted from the long journey, it fell dead.

Its long, white wings, spread on the ground, turned into white beaches.

At the place where the heart beat in the earth, a large and deep depression opened up, which the waters of the sea invaded, and its shores were fertilized by the blood of the legendary bird.

Thus, the primitive lords of the land – the Tupinambás – believed that Kirimuré was born, the vast bay of gentle waters and its Recôncavos, which the white European would later call Baia de Todos os Santos.

However little the records tell us, the first European to penetrate these sheltered waters seems to have been the Portuguese navigator Gaspar de Lemos, commander of the supply ship of the squadron of Pedro Álvares Cabral, who was charged with carrying the letter of Pero Vaz de Caminha with the happy news of the discovery to the king of Portugal, D. Manuel, O Venturoso.

.

This messenger ship, which set sail from Porto Seguro on May 2, 1500, bound for Lisbon, probably anchored in Todos os Santos Bay on May 5. However, the official discovery is credited to the Florentine cosmographer Amerigo Vespucci, who on November 1, 1501 entered the wide bar of this bay, in one of the six ships of the exploratory expedition of Gaspar de Lemos, the same pilot of the messenger ship.

It was customary at that time to name the places where one landed according to the saint of the day on the calendar, and so it was called Baia de Todos os Santos, the great gulf “capable of sheltering, without confusion, all the squadrons of the world”, as a foreign traveler visiting Bahia described it centuries later.

Gaspar de Lemos’ expedition stayed here for about five days.

At a rocky point of the bar that separates the bay of safe waters from the open sea, a stone column – a pattern – was set up, which the Portuguese used to place in places they discovered, as a mark of possession and dominion of the land.

For many years the place became known as Ponta do Padrão.

Between 1583 and 1587, the Forte de Santo Antônio da Barra, or Forte da Barra, was erected on the spot where the monolith with the coat of arms of Portugal was located, whose lighthouse still warns vessels about the presence of rocks and parcels at the entrance to the bay.

The place came to be called Farol da Barra (Barra Lighthouse), a denomination that has remained.

After turning around Ponta do Padrão, you will see the Baia de Todos os Santos in all its vastness.

An immense amphitheater with a contour of approximately 200 kilometers, cut out by inlets, lagoons, lagoons and a small bay, Aratu.

The opening, the large south-facing mouth between Ponta do Padrão and Ponta do Garcez, is about 18 nautical miles (33km) long. Its length in a straight line is 50km, from the opening to the town of São Francisco do Conde; and 35km, west – east direction, from Paripe to the mouth of the Paraguaçu river.

Within the bay are 56 islands of various sizes: Madre de Deus, dos Frades, Maré, do Medo, Grande, Cajaíba, Bimbarras, das Vacas, Maria Guarda, das Fontes, Bom Jesus dos Passos, Pati and in the southwestern portion, the largest of them, Itaparica, with an area of 246km.

Halfway along the western contour of the bay, the Paraguaçu River flows, an indigenous name meaning big river. About 36 km south of the mouth of the Paraguaçu, the Jaguaripe River (or yaguar-y-be, “river of the jaguar”) flows into the place known as Barra Falsa of the Bay of All Saints.

At the beginning of colonial times, the bay and its concaves were populated by the Tupinambás Indians who, not long ago, had expelled the Tapuias, the primitive lords of the land, to the hinterlands.

In Bahia, the Tupinambás dominated along the coast, from the mouth of the São Francisco River to beyond the Jaguaripe River, where the Tupiniquins’ territory began.

The vastness of the waters of the Bay of All Saints offered ships a safe anchorage, earning the preference of navigators on the extensive Brazilian coast.

Since 1504, French privateers have visited the unguarded coasts of Bahia. They were mainly attracted by the lucrative clandestine trade in brazilwood, the red dye of which was consumed on a large scale by the textile industries of the Flanders region.

This trade reached such proportions that at one time it took precedence over the trade of the Portuguese, the masters of the colony.

The French knew how to make alliances with the Tupinambás, facilitating barter. Eduardo Bueno’s interpretation in his book Capitães do Brasil: a saga of the first colonizers is lucid: “the Tupinambás did not need much time to realize that the Portuguese were different from the French.

Unlike the French mair who came to Bahia only to collect the paubrasil – exchanging their goods as friends and, as friends, leaving without arousing suspicion – the Portuguese had arrived to stay and, in addition to taking possession of the land, were willing to enslave the natives”.

In other words, the French did not inspire suspicion in the Tupinambás, unlike the Portuguese, who were prospective masters.

For many years, the Bay of All Saints did not have a single Portuguese establishment, and trade with the French, who were friends of the Indians who inhabited its shores and islands, prevailed.

In 1526, a Portuguese squadron commanded by Cristóvam Jacques was sent to Brazil to sweep the French corsairs from the coast. When this coastguard squadron entered the Bay of All Saints, it encountered three French ships carrying brazilwood in the Paraguaçu River, at the entrance to the Iguape lagoon, in the place that to this day is called the island of the French.

The fight took a whole day. The French were defeated and three hundred crew members were taken prisoner.

The clandestine trade in brazilwood found in Bahia a kind of mercantile agent for the French: the Portuguese Diogo Álvares Correia, who went down in history with the legendary name of Caramuru.

He was shipwrecked on a possibly French ship which, in 1509 or 1511, crashed into the reefs and rocks on the ocean shore one league north of the bay bar, at the place now known as Mariquita beach, a name which is a corruption of the Tupi word mairaquiquiig or “shipwreck of the French”.

The fact that it emerged from the sea among the rocks led the Tupinambás to call it Caray-muru, which in the language of the gentiles means a fish with an elongated body like the eel that lived among the rocks.

Some authors prefer the name to have come from, “the wet, or drowned white man”. However, legend has it that the castaway, coming out of the sea, shot a bird with the rifle he had collected on board, leaving the Indians perplexed to the point of calling him “son of fire” or “son of thunder”.

Caramuru lived 47 years among the Tupinambás, having married and left numerous offspring with the famous Indian woman Paraguaçu, daughter of the powerful chief Taparica, lord of the cannibals of the island of Itaparica. They married in France, probably in 1525, where the Indian was baptized and named Catharina, after Queen Catharina de Médicis.

Legend has it that on Caramuru’s departure for his overseas marriage, an indigenous woman threw herself into the waters of the bay and swam following the French ship, which was carrying her ungrateful beloved, until she met her death. Her legendary name became Moema, mbo-em in the Tupinambás language, “the faint-hearted”, “the exhausted”.

In the Bay of All Saints, it is difficult to separate history, based on documents, from story, a fantasized expression of facts.

Caramuru had a great influence on the beginnings of the settlement. It is curious that French pilots, smugglers of brazilwood, called Pointe du Caramourou the place at the entrance of the bay known by the Portuguese as Ponta do Padrão.

At the end of 1535, the nobleman Francisco Pereira Coutinho arrived in Bahia to settle the captaincy that had been granted to him by King João III, through the letter of donation signed in Évora on April 5, 1534.

The Captaincy of Bahia had fifty leagues (300km) of frontage, counted from the mouth of the São Francisco River to the tip of the Bay of All Saints, including the Recôncavo Baiano from there, including any islands that might be found, and to the hinterland and the mainland, as far as the limit of Castile, the Tordesillas Meridian.

The captain-donee settled in the vicinity of the place where Caramuru lived, with his Indian wife, his Mameluk children and his sons-in-law. On the site, now known as Porto da Barra, Pereira Coutinho built a settlement by the sea to be the official seat of the Captaincy, Vila Velha or Povoação do Pereira.

About a year later, the grantee had a letter of donation drawn up granting Caramuru a sesmaria, thus confirming the lands he occupied with his people.

It did not take long for the Tupinambás to realize that this new invasion of settlers, who came with the grantee, was gradually taking over their lands, their forests and their rivers.

In addition, they oppressed the gentiles into slavery, even selling them to other captaincies. This oppression could not find another outcome: the Tupinambás rose up en masse against the invading white man.

The trigger for this revolt was due to the death of the son of one of the indigenous chiefs, attributed to a relative of the donee himself.

It is true that Caramuru helped the newcomers by providing supplies and facilitating relations with the Indians, but he was not an ally of all the Tupinambás. Nor could he be.

There were many Indian villages scattered along the coast and in the Recôncavo, divided into several tribes, each with its own chief, guarding their forests and fishing grounds.

And it was quite common for them to war among themselves, taking prisoners who they roasted and ate at great feasts, or sold as slaves to outsiders.

The Tupinambás banded together and, with about six thousand warriors – their faces dyed black from the jenipapo, alternating with the bright red of the urucum, which gave them a terrifying appearance – they burned fences, destroyed mills, killed several Portuguese and besieged the survivors in the Povoação do Pereira.

“It was five or six years spent in great hardship”, reported in 1580, the mill owner and historian Gabriel Soares de Souza, “suffering great famines, diseases and a thousand misfortunes and the Tupinambá gentile killing people every day”.

Not enough of this war, the grantee still faced the betrayal of some convicts and settlers who, due to internal rivalries in the captaincy, allied themselves with the Indians, inciting them to fight.

As for Caramuru, everything indicates that he did not take a stand against the Indians who besieged the seat of the captaincy. However, he seems to have been the one who led the old grantee to flee to the Captaincy of Ilhéus. With that, the Tupinambás devastated the town.

While the Captaincy of Bahia was adrift, the French, friends of the Indians, were planning to settle there, stimulated by their ambition to make Brazil a French possession.

This threat of possible French domination prompted Francisco Pereira Coutinho to return to his domains. It was Caramuru himself who persuaded the grantee to leave Porto Seguro, where he was taking refuge, and return to Bahia with the promise of peace offered to the Indians.

In 1547, on the return voyage, the ship carrying Pereira Coutinho crashed into the treacherous reefs of the Pinaúnas, at the southern tip of the island of Itaparica.

This tragic episode was described by Eduardo Bueno: “The donee and most of his companions were saved, but were taken prisoner by the Tupinambás. Upon realizing that among the prisoners was Pereira himself, the Tupinambás decided to kill him.

The one who brandished the club was a five-year-old Tupinambá, brother of a native whom Pereira himself had ordered killed. In the ritual sacrifice, the boy was helped by an adult warrior to deliver the blow that ended Francisco Pereira Coutinho’s life.

The tribe then devoured the donatory’s body in a noisy anthropophagic feast.

Almost nothing remained of the nine years of Pereira Coutinho’s administration. The mills that had been set up in the Recôncavo were burned by the Tupinambás. Pereira’s Vila Velha, what was left of it, returned to its original condition as a “simple nest of Mamelukes”.

The tragic death of the old and ruined Francisco Pereira Coutinho precipitated a complete reformulation of the administrative regime of Brazil, which had long been under study in Lisbon. In general, the whole system of hereditary captaincies had failed.

On March 29, 1549, a Friday, before the sun disappeared behind the island of Itaparica, the prows of three large ships, two caravels and a bergantim, entered the quiet waters of the Bay of All Saints. Commanding the Portuguese fleet was Tomé de Souza, “Captain of the settlement and lands of Bahia de Todos os Santos and Governor of the lands of Brazil”, titles he had held since his appointment on January 7, 1549.

He had come to found “a large and strong fortress and settlement”, the city of Salvador in the Bay of All Saints.

A few months before the Governor’s arrival, an emissary of the king sent a letter to Diogo Álvares Caramuru announcing the coming of the armada and, above all, that he should make a reserve of supplies for Tomé de Souza and his entourage.

With the death of the Donatory, Caramuru had become the most important man in the Captaincy and had already obtained from the Tupinambás the promise of cooperation with the “new” colonizers.

Although the skirmishes with the Indians did not cease, the Governor managed, with Caramuru’s help, to begin to establish peace between settlers and Indians.

Further into the bay, to the north, a little less than half a league from the village of Pereira under one of the bluest skies in the world, the Governor planted the fortress city on top of an escarpment, facing west, dominating the Bay of All Saints.

The Indians cooperated with the numerous artificers who, under the orders of Master Luis Dias, erected the city.

Initially, mud huts, then came the stone and lime houses, and the city would rise with arrogance, seventy meters high, looking at the bay; and would become a city of art, with its baroque excesses and its animist cults, the metropolis of the Bay of All Saints and its Recôncavos, the city of Bahia, seat of the Portuguese colonial government for 214 years.

Eight years after the foundation of the city of Salvador, in 1557, death ended the troubled life of Diogo Álvares, Caramuru.

It fell to Mem de Sá, the third Governor-General of Brazil, to pacify the wild Indians with the help of Jesuit missionaries.

When necessary, the Governor did not hesitate to invade the lands of the rebellious tribes and destroy the villages that tried to resist. More than one hundred and thirty villages were destroyed. Mem de Sá was a great promoter of sugar cane cultivation in the region.

He even built a royal mill with its water wheel to receive the cane from farmers who did not have their own. Sugar mills flourished on the lands of massapê, a deep clay that sticks to shoes.

Cane farming and sugar production became typical and basic activities of the Recôncavos.

The cane fields and mills bordered the entire bay, from Salvador to Barra do Jiquiriça and the lands of Jaguaripe, where Gabriel Soares established his mills; they spread to the Santo Amaro and São Francisco do Conde tabuleiros, and went up the flowing Paraguaçu.

In the last quarter of the 16th century, there were already a good number of owners of vast sesmarias and sugar mills well set up in the Recôncavo, with a large number of slaves. These mills were not simple farms, they were settlements.

From them the towns and cities of the Recôncavo were born.

For a long time, communication between these cities was made exclusively by the Bay of All Saints and the rivers that flow into it. Then came the railroads and highways that broke the isolation. Sugar mills became sugar factories.

Tobacco occupied the lands of the Cachoeira – São Félix – Maragogipe area. In the 20th century, the tall silhouettes of oil wells dotted the fields, where before the wind whipped the cane fields. Industries sprang up.

A new era of transformation. The prosaic sloops and steamers gradually gave way to schooners, sailboats and catamarans.

Cars now ply the waters of the bay in the belly of ferries.

However, the testimonies of the past remain in the austere architecture of colonial mansions with their facades dressed in Portuguese tiles, in the monumental churches, in the silence of the convent cloisters, in the water wheel of the mills, in the silver implements and the imagery of the altars, in the ships and caravels that sleep under the waters, in the cannons of the old forts that still peek over the horizons guarding the bay and in the mestizo memory of the people of Bahia de Todos os Santos.

THE GREAT VOCATION OF BAÍA DE TODOS OS SANTOS

Bounded at its extremities by the Barra Lighthouse and Ponta do Garcez, the Bay of All Saints mixes beauty, history and culture, visualized in handicrafts, typical cuisine and architecture, which transforms it into a great setting for nautical tourism and ecotourism activities.

This scenery is composed of a surface of calm waters of 1.052 Km2 of extension, shelters islands, beaches and receives the fresh waters of innumerable rivers and streams, being the main ones the Paraguaçu, the Jaguaripe and the Subaé, besides having leaning in one of its extremities, the first capital of Brazil and the biggest of the Northeast: Salvador of Bahia.

In its surroundings are located the municipalities of Itaparica, Vera Cruz, Jaguaripe, Nazaré, Salinas da Margarida, Maragogipe, São Félix, Cachoeira, Santo Amaro, Saubara, São Francisco do Conde, Madre de Deus and Candeias, among many others that make up the Recôncavo Baiano.

In Bahia, the word Recôncavo gained a new dimension, with a capital letter, to identify the region around this bay.

To ensure the protection of its islands, ordering the socio-economic activities present in the area and preserving sites of great ecological significance, the Baía de Todos os Santos Environmental Protection Area was created through State Decree no. 7.595, of June 5, 1999.

The APA has an approximate surface of 800km2, including the waters and islands of the Bay that present remnants of Atlantic Forest, mangroves and restingas, sheltering diversified fauna and flora.

NATURISM IN THE BAÍA DE TODOS OS SANTOS

In the past, it was the largest seaport in the Southern Hemisphere and is currently the target of major public and private investments aimed at increasing nautical tourism and ecotourism.

A large private marina has already been implemented in the Bay of All Saints, near the Lacerda Elevator, which today already houses 300 spaces for boats of any size, with all the infrastructure.

of any size, with all the modern infrastructure available.

On the other hand, the Bahia Nautical Center, an initiative of the State Government, in addition to housing boats, promotes and coordinates nautical activities in the State.

Traditional regattas such as the João das Botas Sailboat Regatta, the Aratu – Maragogipe Regatta and the international ocean races Rally les Iles du Soleil and Hong Kong Challenger take place throughout the summer season and beyond.

The Mar Grande – Salvador crossing is the main competition that takes place annually within the Bay during the summer.

In addition to this, there are other races within the Bahian Open Water Circuit: Salinas, Itaparica – Ponta de Areia, Itacaranha – Ribeira, São Tomé de Paripe – Porto da Barra.

The attraction of nautical events to the Bay of All Saints is based on its historical trajectory, which has seen ships and caravels, canoes of the native inhabitants, sloops – which over time have become the most characteristic vessel and means of transportation in the area – to modern ocean-going sailboats, luxury liners, even the yacht of Queen Elizabeth of England.

The largest and main celebration that takes place annually in its waters is the Procession of Senhor Bom Jesus dos Navegantes, on January 1st, when the galley Gratidão do Povo leads the image of Bom Jesus on a long journey from the Cais do Porto to Porto da Barra and from there to the Igreja da Boa Viagem, accompanied by hundreds of boats.

Another unique aspect of Todos os Santos Bay is the combination of the beauty of the natural and historical scenery hidden beneath its waters. These scenarios reveal surprises for diving enthusiasts, who come across the formation of coral reefs and wrecks of ships wrecked throughout its colonization.

It is good to know that in front of Porto da Barra, at a depth of 12 meters and with a visibility of 10 to 15 meters, there are beautiful coral reefs. For experienced divers, the outer or “Wall” corals are in the middle of the Bay, between Itaparica and Salvador. The walls, a mile from Salvador, are between 25 and 45 meters deep and at high tide, visibility varies between 15 and 20 meters.

The coral formations and reefs near the Tidal Islands have a maximum depth of 11 meters and visibility of up to 15 meters horizontally.

In front of the port pier, on the north breakwater, there is an interesting spot for night dives with a large amount of marine life. In front of Aratuba beach, in Itaparica, the Pontinha and Caramunhãs coral reefs, two miles from the coast, offer rich underwater scenery.

The ghosts of history have also become a target of interest for divers in search of treasure, research or curiosity.

Between battles, invasions and storms, there were several vessels that sank in the Bay of All Saints and the best known and historically recorded are: The ship Nossa Senhora de Jesus, 1610 – attacked by Dutchmen from the Companhia das Índias it sank in front of the fort of Santo Antônio da Barra, at the entrance of the Bay; seven Portuguese ships, 1624 – they were set on fire and sank in front of the slope of the current avenue Contorno; two Flemish and one Lusitanian ship, 1627 – went to the bottom of the sea at Preguiça beach during the fight between the Portuguese and the Dutch for the possession of the city of Salvador; two Dutch and one Portuguese ship, 1647 – sank after another sea battle near the Fort of Monte Serrat, the ship Santa Escolástica, 1648 – sank at the exit of the Bay; the galleon Nossa Senhora do Bom Sucesso, 1700 – sank in front of Preguiça beach; Spanish galleon San Pedro, 1714 – sank in the same place; galleon Nossa Senhora do Rosário, 1737 – sank in Monte Serrat loaded with jewels, gold, crockery, amber and pepper; the wreck of the ship Bretanha, known as “Navio de Dentro”, is near the Barra Lighthouse protected by corals, and is an ideal spot for baptism dives.

ECOTURISM IN THE BAÍA DE TODOS OS SANTOS

The verb conjugate is always present when talking about the Bay of All Saints: conjugate the sea and the land, the old and the new, the legends and the history. This is how the ecotourists’ “discovery” gaze comes across the possibilities of visiting its islands and the region of Recôncavo Baiano, where the marks of Portuguese colonization and the miscegenation between European, African and indigenous cultures are strong.

The 56 islands that form the archipelago of Baía de Todos os Santos have common characteristics, such as beaches with crystal clear waters, calm sea, dense vegetation, predominantly mangroves, coconut groves and banana plantations, as well as traces of the Atlantic Forest.

Of the existing islands, the main ones are: Itaparica – the largest sea island in Brazil -, Madre de Deus, Maré, Frades, Medo, Bom Jesus dos Passos, Vacas, Capeta, Maria Guarda, Joana, Bimbarras, Santo Antônio, Cajaíba, Cal, São Gonçalo, Matarandiba, Saraíba, Mutá, Olho Amarelo, Caraíbas, Malacaia, Porcos, Carapitubas, Canas, Ponta Grossa, Fontes, Pati, Santos, Coqueiros, Itapipuca, Grande, Pequena, Madeira, Chegado, Topete, Guarapira, Monte Cristo, Coroa Branca and Uruabo.

The Bahian Recôncavo, rich in folklore, cuisine and the arts of its dark people, shows the marks of its past in the historic cities and in the almost 400 old sugar mills that populated the region during the colonization of Brazil.

It keeps a past of riches and heroic acts of its people who, practically unarmed, fought against foreign invasions and sugar mill owners united in support of D. Pedro I, fighting bravely against the Portuguese, for the independence of Brazil.

To know the Recôncavo Baiano is to be dazzled by the baroque architecture of the 18th century, in cities such as Cachoeira, São Félix, Santo Amaro, Jaguaripe and Nazaré, which were born, developed and experienced luxury and opulence during the sugar cane, tobacco and cattle cycles.

With the abolition of slavery in Brazil, the economy of the Recôncavo declined and the mill owners went bankrupt.

The families of the big house moved to the capital of the province, leaving behind villages, cities, beautiful colonial buildings and the lands of the massapé. A world of memories that has crumbled over time.

It is also to delight in the typical cuisine that combines, in the right measure, the influences of the three races in dishes watered with palm oil and the most varied sweets, liquors and spirits; it is to discover natural beauties hidden in the Paraguaçu and Jaguaripe rivers throughout the area of influence of their estuaries in the Bay of All Saints, in the Iguape lagoon, on the beaches of Saubara.

Religiosity, mysticism and history are the hallmarks of the Recôncavo, all framed by extensive sugar cane fields, rich mangroves and what remains of the rainforest.

History and Tourism of the Bay of All Saints