Este post também está disponível em:

Português

English

According to Simões (1980), the main characteristics that distinguish Portuguese tiles in the first 25 years of the 17th century are monumentality, suitability for architecture and modernity.

The Portuguese tile arrived in Brazil in synchrony with the other arts and followed the same process of acculturation existing in Portugal.

In other words, the same taste, technique and materials from Portugal were transported to Brazil.

During the 17th century, tile-making developed in both countries and reached high decorative levels.

In Brazil, tile coverings with polychrome patterns, forming carpets framed by borders, did not reach the monumentality of Portuguese examples, but were well represented in Pernambuco and Bahia.

Tastes, fashions, customs, in short, almost everything the Court produced was brought to the Colony at the same time.

The same thing happened with tiles.

At the end of the 17th century, polychrome ceramics in the Italian style lost place to the novelty of blue porcelain, imported from China, and then copied in Holland, England and Italy itself.

Veja Evolution and History of Plastic Arts in the Northeast and History and Chronology of Portuguese Tiles.

Videos about the history of the introduction of Portuguese tiles in Brazil

Portuguese tiles began to reproduce the old polychrome patterns in two shades of blue.

The best examples of this genre were sent to Brazil, such as the blue-patterned tiles that lined the interior of the church of Nossa Senhora dos Prazeres in Montes Guararapes, Pernambuco (SIMÕES, 1980).

Technically, this change to blue monochrome represented a simplification of production processes.

The use of cobalt, which produces the blue tones, was easier than the other colours, as was its better behaviour in firing operations.

At the end of the 17th century, there were both polychrome and monochrome tiles, but the latter gained popularity.

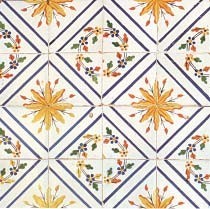

During that century, the tiles most commonly used in the interiors of temples and noble houses were large carpet compositions, achieved by repeating the polychrome pattern (element).

Both schemes of four tiles (2×2) and schemes of sixteen (4×4) to thirty-six (6×6) tiles were used.

Patterns were defined by the modulus of the repetition. For example, a 2×2/1 pattern meant a repetition of four tiles to one element.

In order to cover larger surfaces, more complex repetition patterns such as 4×4/2, 4×4/3, 4×4/4, 6×6/8 up to 12×12/14 were manufactured and used.

The carpets were then limited by friezes (rectangular fractions of tiles), borders (total tile) or bars (two tiles overlapping). These accessory elements of the carpets had their own corners to give ornamental continuity to the connecting angles (SIMÕES, 1980).

Bardi (1980) explains that the carpet application could also be composed of figures, where the square card was prepared and the artists transferred the drawing to the tiles.

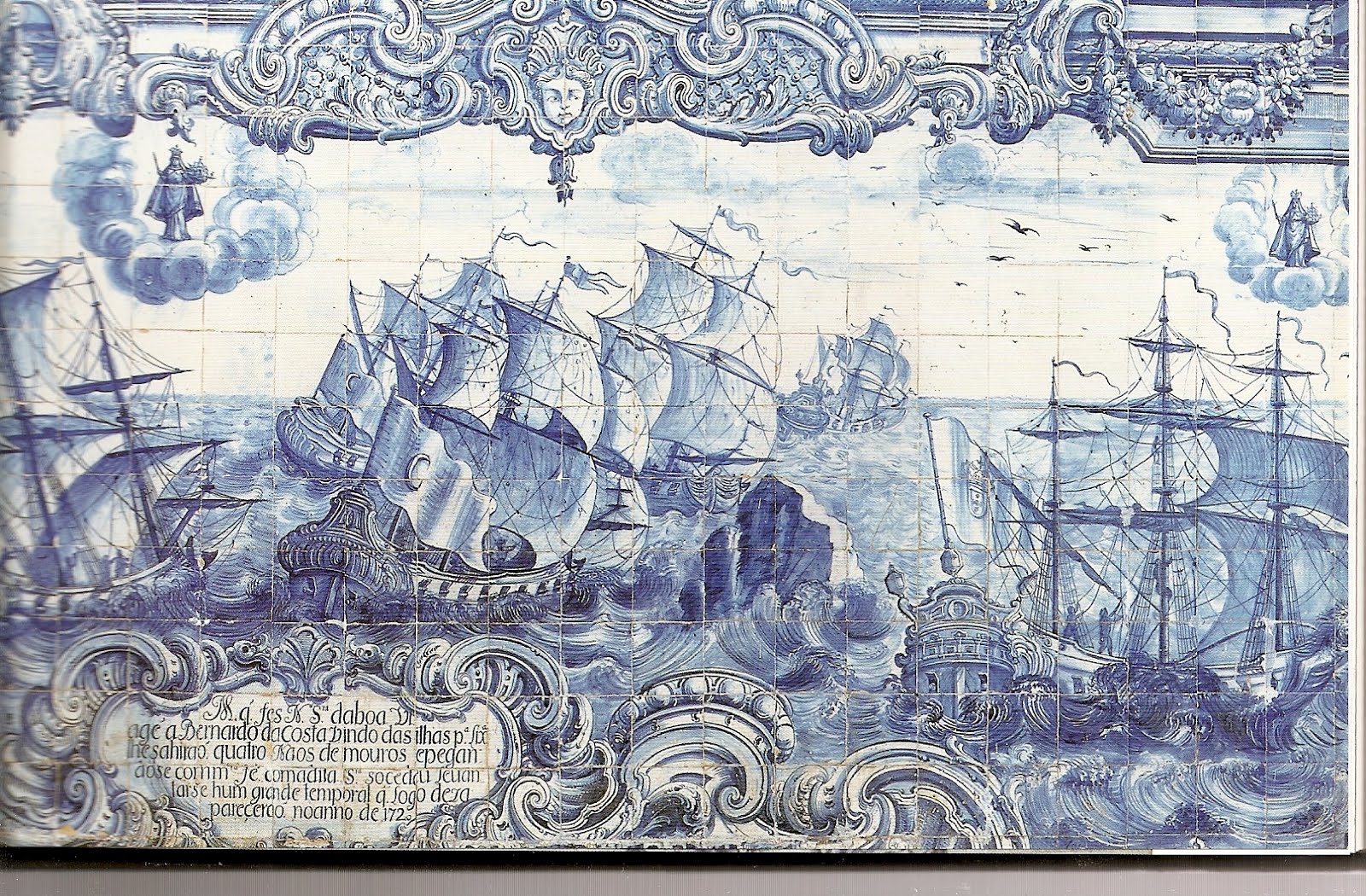

Figurative themes included the lives of saints, scenes of mercy, civil, maritime and mythological themes, and episodes of domestic life.

During the occupation of the Dutch in Pernambuco (1630 to 1654) tiles came from Holland for the palaces built at the time of Prince Nassau.

Generally, the pieces had a central figure inside some kind of frieze, or just a popular figure and the corners containing drawings of spiders, Chinese labyrinths, ox heads or fleur-de-lis.

The pieces were not as well finished as the Portuguese ones and had smaller dimensions (CAVALCANTI, 2002).

It is interesting to note that already in this century (17th), in Setúbal, Portugal, the parietal coverings began to show concern with scale.

When the tile was closer to the view, the chequerboard was smaller.

At the highest part of the panel, the scale of the chequered pattern was increased, compensating for the distance.

The composition suggested carpets and bars and there was a concern to follow the existing shapes, such as a staircase (ALCÂNTARA, 2001).

In the 18th century, the Marquis of Pombal, Prime Minister of King João VI, implemented a manufacturing industrialisation programme in Portugal.

The Loiça do Rato factory was created, which simplified the existing tile patterns.

The products were made in series by artisanal processes, which increased production, making the price of the tile more accessible to a larger audience (ALCÂNTARA, 1997).

According to Simões (1965), the 18th century is characterised by having also been a period of artisanal techniques, where some Portuguese masters of tile painting stood out.

They were the so-called ‘artist painters’, who used the tile with the intention of making a work of art and generally painted large figurative and signed compositions, establishing the genre of monumental painting, also widely used in Brazil.

The author also informs that the 18th century, a period of great export of Portuguese products to Brazil, was the century in which Brazil became the great provider of Portugal.

This provided the Colony with a great increase in its artistic heritage and the presence of Portuguese tiles in Brazil was very significant, both in the quantity and quality of the examples, where the use of cobalt blue incorporated into white backgrounds continued to exist.

“It can be said with truth that the Kingdom returned to Brazil in enamelled clay part of the gold and stones it received from there and, if the gold has long since disappeared from the coffers of the state, it is represented forever in monuments, carvings, images, implements, vestments, silverware and… in the tiles, which on either side of the Atlantic, affirm the magnanimous presence of King João V and his splendid era!” (SIMÕES, 1965, p.29).

According to Simões (1965 and 1980), tiles were definitely linked to architecture during this period, becoming indispensable for embellishing temples and manor houses and were ordered both in the Kingdom and in the Colony with the same care and requirements.

The tile, which was becoming indispensable as a decorative element, found in Brazil other reasons for its great acceptance.

The scarcity of materials for external finishing of façades, together with the hot and humid climate of the Brazilian coast, which made conservation and waterproofing difficult, may have led the builders of that century to use the tile, more economical (due to its durability), to decorate and also guarantee the good conservation of the façades of churches and land in front of and/or around churches.

Thus the ‘Azulejo de Fachada’ (façade tile) emerged in Brazil, unknown in Portugal.

Simões (1980) informs that the 18th century was the period of fixation and ‘nationalisation’ of the tile, that is, the use of the tile in architecture was confirmed as a normal and typically Brazilian trend.

The tile began to be used with representations of figurative themes and reduced to monochrome lost decorative quality.

However, it soon became popular due to the excellence of the materials used and the care taken in painting. The religious orders, especially the Capuchin friars, retained the greatest artistic wealth of the period.

Countless Brazilian convents, hospitals and missions were richly adorned with Portuguese tiles.

Along with the production of figurative panels designed and executed for specific places, the so-called ‘ornamental tiles’ were produced in Portugal, produced in series, for simpler decorations and could be bought by units, dozens or hundreds.

Independent of predetermined places, they allowed various combinations and were more affordable, being used in secondary rooms such as corridors, small rooms and kitchens.

Within this type of ornamental tiles are the so-called ‘single figure’, where each tile contains an independent motif with simple designs and a certain naivety, painted in blue, with themes of flowers, birds, animals, human figures or boats.

They were produced in Portugal and became the ‘popular’ tiles, always graceful, but not many examples are found in Brazil.

Another type of serialised tile was the panels of flowered vases, the so-called ‘azulejos de vasos’, found more frequently in Brazil, almost always framed by figures of mermaids, dolphins, little angels or baroque volutes (SIMÕES, 1965).

During the 18th century, there was a great variety of styles of tile designs and paintings that reflected contemporary fashions and tastes.

Santos Simões in Azulejaria Portuguese Tiles in Brazil divided the 18th century into four periods that differed pictorially: the era of the masters (1700-1725); the era of the anonymous workshops (1725-1755); the Pombaline era (1755-1780); and the era of Queen Maria I (1780-1808).

Cavalcanti (2002) used the same chronological division to show the different types of designs characteristic of each period.

In the second half of the 18th century, with the rococo period, dissymmetry and arrhythmia became predominant, with the return of polychromy in arrangements of shell mouldings in yellow, green, purple and blue tones.

During the 19th century, several historical events and facts disrupted Brazil’s relations with Portugal.

In 1808, the court of King João VI arrived in Brazil and Brazil’s ports were opened to international trade.

Portugal was devastated by the wars and lacked resources, it was no longer the supply centre and with the ease of trade, Brazil began to import tiles from other countries such as Holland, England, France, Belgium, Germany and Spain.

However, the products of these countries were different from those of Portugal. According to Cavalcanti (2002), the tiles from these countries had industrialisation characteristics such as thin paste, small and standardised dimensions, smooth glaze, reduced thickness of the biscuit and also stamped or decal decoration.

Brazilian builders used tiles to clad and protect the façades of buildings. In fact, there is some controversy among scholars regarding this creation or innovation of the use of tiles on façades.

Portuguese historian Santos Simões categorically states that this is a Brazilian invention, while Brazilian experts Dora Alcântara and Mário Barata attribute it to Portugal.

In addition to embellishing façades, the tile had the utilitarian function of protecting against humidity, typical of our tropical climate, aggravated in coastal cities or cities located on the banks of rivers, due to salinity.

The tile waterproofed and insulated the exterior, ensuring better and longer conservation. The cities that most received tiled façades were those with such geographical characteristics as Belém, São Luiz, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre and Recife (CAVALCANTI, 2002).

The author reveals information that can confirm the beginning of the application of tiles in civil architecture.

The first news of the arrival of a shipment of tiles was published in the Diário de Pernambuco in 1837. The news informs that 1,400 tiles were brought on a Spanish ship from Rio de Janeiro.

It does not inform, however, the origin of the ship, probably from Portugal, where all the first tiles came from.

Other reports published in the following years, 1838, 1839 and 1840, already specify that ships coming from Lisbon brought boxes of tiles from Portugal.

Regarding the use of tiles in façade cladding, Alcântara (2001) continues to question whether it is a Brazilian creation. In his opinion, this practice was established simultaneously in Brazil and Portugal.

There is documentation and examples of tile cladding on the ends of bell towers from the 16th century in both countries; in Portugal there have also been tile-clad garden benches and garden façades lined with tiles since the same century.

The author notes that, in Portugal, from the Liberal Revolution onwards, and with the rise of the bourgeois class, the tile was chosen by this social group that did not have refined aesthetic taste according to the standards of the time.

The semi-industrialised tiles met the needs of this emerging class. As the sobrados were semi-detached, there was only one apparent façade, which was the front one where, naturally, the tiles were laid.

In Brazil, the phenomenon was similar. The country became an empire and the need arose to enrich its simple architecture.

The Portuguese who lived in Brazil and returned to Portugal built their “Brazilian houses” with the new taste or fashion – tile-covered façades -, observes Simões (1965), verifying and defending his idea that the use of tiles on façades thus proliferated in Portugal.

As soon as order was restored in Portugal and trade relations with Imperial Brazil were re-established, Portuguese tiles regained their lost position and soon surpassed foreign tiles.

Between 1860 and 1918, Portuguese tile factories again supplied Brazil.

The manufacturing process used at the time was semi-industrial stamping, the most common.

It consisted of applying a mould, usually made of metal, with the designs cut out, and applied to the ceramic tile and, finally, the craftsman coloured the open space with a brush.

For polychrome patterns, a mould was made for each colour. Many of the pieces produced in this way turned out to be defective, but they were still used.

In the technique used prior to stamping, the motif was drawn on a card and perforated, this card was placed on the tile and a very fine charcoal powder was passed through the holes marking the outline of the drawing on the tile.

The tiler then used a brush to outline these contours, completing the figure. The stamp allowed the reproduction of smaller drawings with more details (ALCANTARA, 2001).

The production of painted and glazed tiles was not successful in Brazil during the 19th century.

The first Brazilian factory was installed in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, around 1861 and was called Survillo & Cia. During the nineteenth century there was, in Brazil, great use not only of Portuguese tiles but also those of other origins such as the French.

In these two countries, tiles were produced with some particularities or differences.

Cavalcanti (2002) documented the differences between Portuguese and French tiles found in Pernambuco in the 19th century.

In terms of size, the Portuguese ones measured 13×13 and 14×14 centimetres and the French ones measured 10.5×10.5 and 11.5×11.5 centimetres.

In the blue and white modality, the Portuguese had a clearer blue design on a white background than the French (which had a blue smoky colour around the design).

Portuguese tiles were often divided into 2×2 and 4×4 modules, while French tiles had the pattern on the tile itself.

The author also emphasises that Portuguese tiles were surrounded by friezes (half of the tile) of the same or similar pattern, forming gaps and marking the lower bar.

The French type of tile did not use friezes, they rarely had cercadura which were tiles in the same dimensions as the main tiles but with a different pattern.

Still in relation to French tile patterns, Alcântara (2001) refers to a factory in Dèsvres, in northern France, specialising in crockery, which later went on to produce tiles as well; it was common for factories to have this dual function.

The raw material for this factory was obtained from the River Plate and with the interest of the South American coastal cities in tiles, the factory began to produce them to be used as ship ballast.

The tiles were sold near the end of the voyage.

The author reveals a French decoration technique where the design was engraved on a metal plate, transferred to paper by chemical action, then placed on the tile’s tin base and taken to the oven, where the paper was burnt or loosened, leaving the printed design.

With this technique, the motifs could be much more elaborate and the images had characteristic pigmentation, dots typical of some prints.

Returning to the tiled façades, Alcântara (2001) believes that São Luis, the capital of Maranhão, has the most interesting set of tiled façades, although Belém has a larger set, despite many losses.

With the rubber cycle in the Amazon, both São Luiz and Belém were capitals of the state of Grão Pará.

São Luis grew rich in the first phase. At the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century, the economy of Maranhão declined, and the rubber cycle began in the Amazon. Belém went through a phase of enrichment, documented even by tiles.

Manaus also grew wealthier during this period, as shown by its tiled townhouses.

With regard to the arrangement of the tiles, the author observes that in several Brazilian cities there is a fanciful composition with various patterns on the same façade.

However, in São Luiz, the pattern is unique in each cladding.

In this city, it is common to find the lower parts of the walls painted in darker colours, as a way of protecting the wall from rain splashes in streets without pavements, a habit that remained even when unnecessary.

In São Luiz, there were examples of the lower part of the façades covered with tiles of different patterns, or with the same pattern, but in a different arrangement.

The author also reports that several other Brazilian cities have had tiling on their façades.

In Rio de Janeiro, there are few traces of tiled façades left, perhaps due to the very rapid transformations. Salvador also had a set of tiled facades, but what remains today is not very expressive.

Recife, Olinda, Paranaguá, Porto Alegre and even cities in the interior such as Sobral, in Ceará, and the cities of the Jaguaribe Valley have tiled facades.

The presence of tiles, sometimes of the same pattern, was found in distant cities within the great Brazilian territorial extension.

The use of façade tiles is high in Brazil, but in Portugal the concentration of this use is much higher. It is regrettable that we are losing much of our cultural heritage.

The sets of tiled façades in Brazil have not been preserved as they deserve. They are disappearing.

The tiles, besides being a decorative material, are documents of this long process of consolidation of our culture.

The First Sanitary Code of 1894 refers to kitchens and bathrooms containing waterproof bars 1.50m high, the text suggests that houses should be dry, ventilated, illuminated and easy to clean (LEMOS, 1999).

Alcântara (1980), identified problems in the architectural scale in the external tiling of façades.

With the tendency for buildings to grow vertically, the tile lost its decorative function, as the motif, which should have been small, disappeared when far away from the observer, which showed a lack of care with the architectural scale in the application of the tile.

With the ease of copying models and the import of foreign matrices, the tile lost its characteristic of exclusivity.

At the same time, this loss of attributes resulted in the gradual disappearance of external tiling for decorative purposes.

The use of tiles was then restricted to internal service areas, such as kitchens and bathrooms, with an exclusively utilitarian function.

The loss of the traditional attributes of Portuguese tilework, such as permanent modernity, striking individuality and suitability to the architectural scale, coincided with the gradual disappearance of decorative façade tiles, both in Portugal and in Brazil, concludes Alcântara (1980).

History of Tiles in Brazilian Culture

Tiles on Portugal street in São Luís do Maranhão

A rua Portugal é a mais azulejada do Brasil

There is the Rua Portugal in São Luís do Maranhão, which has the largest number of tiles on the facades of historic mansions in both Brazil and Latin America.

In addition, the Casa do Maranhão is a great place to get to know the cultural manifestations, histories and geographical aspects of the state.

History Behind the Portuguese Tile

The Portuguese tile is one of the brands that represents the culture of Portugal.

Museu Nacional do Azulejo • Lisboa • Portugal

It took root in the Iberian Peninsula from the late 15th century onwards.

Icapuí no Ceará

Pesca da Lagosta no Ceará

Icapuí - Pontos Turísticos

Icapuí - Guia Turismo Completo08:25

To talk about the history of the Portuguese tile, we must refer to its origin. The influence of Muslim ornamental decoration had a strong impact on Portuguese tile culture.

In practical terms, the Portuguese tile is called a square ceramic plate, of little thickness, generally in the measures 15×15 cm or in smaller formats.

This artefact has one of its faces decorated and glazed, the result of the firing of a coating usually dominated as enamel, making it waterproof and shiny. Its use is also common in countries such as Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, Turkey, Iran or Morocco.

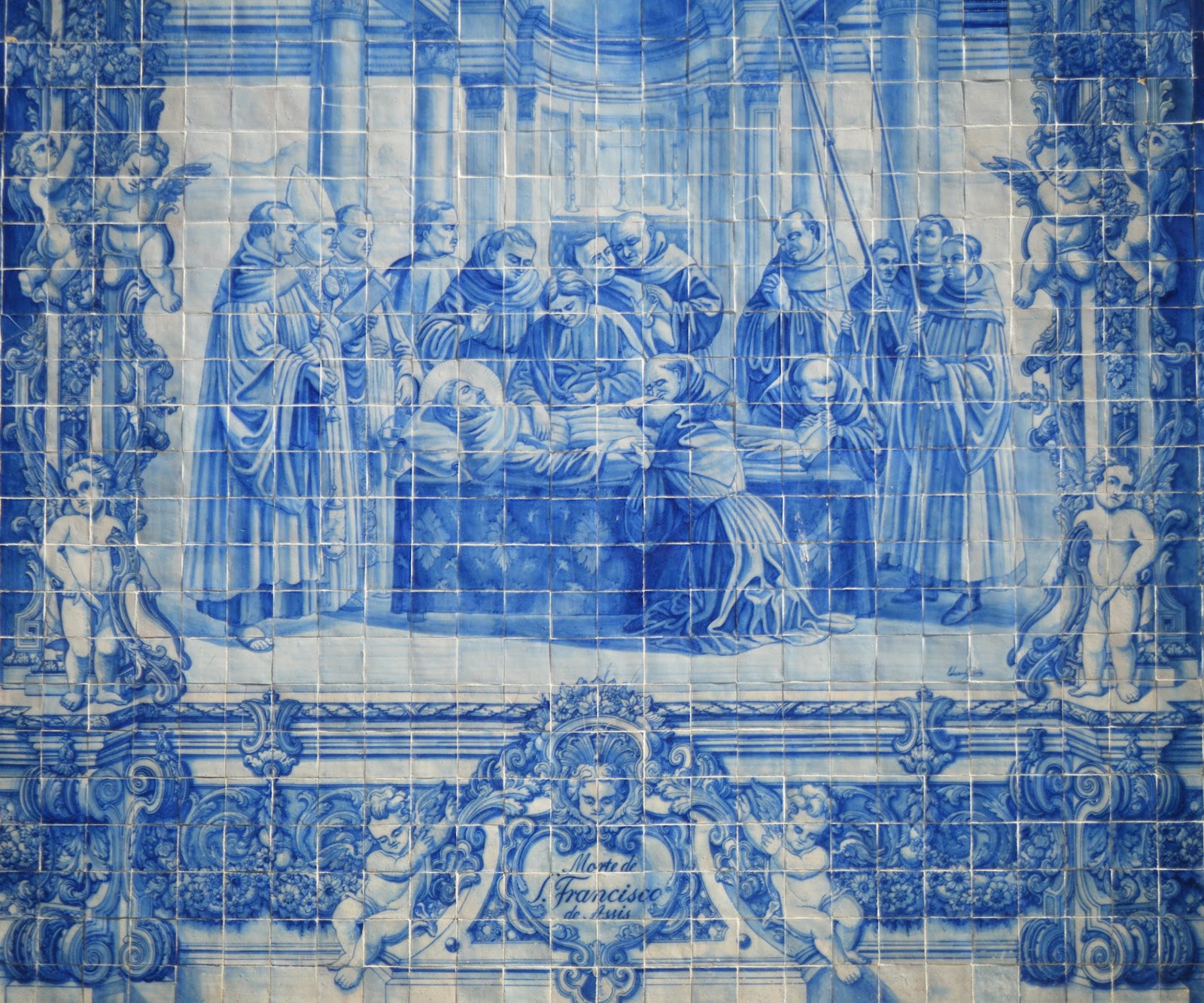

“Death of St Francis of Assisi” (1929), panel located in the Chapel of the Souls, in Porto

History and origin of the Portuguese tile

With the beginning of its spread in the 16th century throughout the Iberian Peninsula, the development of the tile was in charge of the ceramics of Seville.

It arrived in Portugal in 1498, by King Manuel I, on one of his trips to Spain.

Portugal learnt the method of manufacture and painting, and the Portuguese tile became one of the strongest expressions of its culture.

The brilliance, exuberance and fantasy of the ornamental motifs came from the Orient.

From China came the blue colour of porcelain, which, in the second half of the 17th century, gave tiles compositions without a repetitive character, full of dynamism and moving shapes.

At the end of the 17th century, Portugal imported large quantities of tiles from Holland, absorbing the purity and refinement of the materials, as well as the idea of specialising painters.

During the reign of King João V (1706-1750), tiles were influenced by the Talha style, utilising the same motifs in a trend for entire wall surfaces to be covered, creating a distinctive Baroque impact.

During this period, Portuguese tiles were widely used in churches, palaces and houses belonging to the bourgeoisie, inside and outside in their gardens. It was considered a means of social distinction.

The foreign engravings that circulated in the country inspired the compositions of the figurative panels.

After the earthquake of 1755, the fragile economic situation and the need to rebuild Lisbon led to a utilitarian and practical conception of the tile, used as a complement to aesthetic factors.

With the return from Brazil, Portuguese tiles began to be used as cladding on the facades of buildings, given the duality of this material.

Artistic creation in Portugal

Despite its common use also in other countries, in Portugal, the tile assumes a special role in artistic creation, either by the longevity of its use, or by the way of application through the great interior and exterior coverings, or by the way it has been understood over the centuries, not limited only to decorative art.

Figurative tiles were designed in harmony with the space, sacred or civil.

The Portuguese tile is the main actor in a veritable repertoire of engravings. It is the protagonist of historical, religious, hunting and war scenes, among others, applied to walls, floors and ceilings.

The first renowned artists

The forerunner in Portuguese tile painting was the Spaniard Gabriel del Barco, active in Portugal at the end of the 17th century.

In the 18th century, there was a crescendo of artists from the acclaimed Cycle of Masters, during a golden period of Portuguese tilemaking. Reference names include Nicolau de Freitas, Teotónio dos Santos and Valentim de Almeida.

The presence of the Portuguese tile until today

Tiles have been produced in Portugal for 500 years. In the second half of the 19th century it became more visible.

The tile was used to cover thousands of façades and was produced by factories in Lisbon and the cities of Porto and Vila Nova de Gaia, such as Massarelos and the Fábrica de Cerâmica das Devesas.

In the North, the pronounced reliefs, the volume, the contrast of light and shadow are present characteristics. In Lisbon, the preference was for smooth patterns of ancient memory and an ostentatious exterior application on the façades.

In Porto, in the 20th century, the painter Júlio Resende built figurative compositions in tiles and ceramic plates since 1958, reaching the exponent of his work with Ribeira Negra, in 1985.

At this time, the artists Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro and Jorge Barradas emerged, driving the renewal of ceramics and tiles.

Still in the middle of the century, Maria Keil did a remarkable work for the initial stations of the Lisbon metro, joining Júlio Resende (“Ribeira Negra” – 1984), Júlio Pomar, Sã Nogueira, Carlos Botelho, João Abel Manta, Eduardo Nery, among others, as great references in the history and culture of Portuguese tile.

Some places where you can see Portuguese tile panels

- Estação de São Bento, Porto

- Igreja de Santo Ildefonso, Porto

- Igreja dos Congregados, Porto

- Capela das Almas, Porto

- Igreja de Nossa Senhora dos Remédios, Lamego

- Convento de Santa Cruz do Buçaco, Buçaco

- Convento de Cristo, Tomar

- Igreja de São Quintino, Sobral de Monte Agraço

- Quinta da Bacalhoa, Lisboa

- Capela de São Roque, Lisboa

- Convento da Graça, Lisboa

- Convento de São Vicente de Fora, Lisboa

- Palácio dos Marqueses de Fronteira, Lisboa

- Palácio Nacional de Queluz, Lisboa

- Casa de Ferreira das Tabuletas, Lisboa

- Palácio da Mitra, Azeitão

Travel through the history of the Portuguese tile

You can discover the entire history of Portuguese tiles, following their evolution, at the National Tile Museum, created in 1980.

In addition to the national repertoire, it emphasises the intersection with multicultural expressions and their development.

The Portuguese tile is one of the characteristics that puts Portugal in the spotlight in the itineraries of any traveller. In fact, Portugal is considered the tile capital of the world.

Northeast Tourism Guide

History of the introduction of Portuguese tiles in Brazil